By bush plane, canoe and dog sled, a traveler experiences the priceless landscape threatened by the proposed Ambler mining road.

EDITOR’S NOTE: In recent weeks, President Trump and Department of the Interior Secretary Doug Burgum have announced next steps towards building the disastrous 211-mile Ambler mining road through America’s largest national park landscape. Alongside local, Tribal, and national partners, NPCA and Trustees for Alaska have long argued that the ecological, economic and social impacts to the lands and communities of Alaska’s Brooks Range far outweighed any speculative benefits from this proposed mining project. One of NPCA’s longtime supporters shares what’s at stake in this priceless, enduring landscape. The story has been updated since its original posting Oct. 7.

I am on a mission to visit all 63 National Parks. And not just to drive through them, but to really dig into each park and try to understand and experience why these places have been preserved and protected through both congressional action and presidential signature.

In 2024 and 2025, I explored Gates of the Arctic National Park & Preserve and was forever changed by the experience.

It’s not easy to get to this park. There are no roads, no trails, no signs, no visitor infrastructure. Visiting this park is not something you do on the spur of the moment, and it requires lots of advanced planning. Luckily, I found John Gaedeke, a Brooks Range wilderness guide with a generations-long connection to the lands within and just outside what is now the boundary of Gates of the Arctic National Park & Preserve. We began to correspond, and with that, my dream turned into a real plan. He would teach me how to dogsled, and if I was strong enough to do it, he would guide me into Gates of the Arctic. Sixteen months later, my husband and I boarded a tiny 1956 de Havilland Beaver bush plane from Coyote Air in Fairbanks and took off into a cold sunrise, with me in the co-pilot’s seat.

Flying over the frozen Brooks Range gave me a perfect introduction to what this vast wilderness is — and what’s at stake. With mountain after mountain spreading around us, we dodged clouds swallowing peaks, while endless braided ribbons of frozen streams and rivers curlicued below. We covered over 200 miles of this beautiful terrain before landing on a frozen lake. As I disembarked, I immediately understood the fundamental truth of this landscape: without an experienced guide like John Gaedeke, I would not survive.

We wasted no time getting started. I met John’s friend and mushing expert, Thom, who got me set up with my dog team, taught me how to harness them to my sled, and gave me a few simple commands for the dogs. For three days I practiced, learning to help push the sled uphill with my back foot, and then stomp on the footpad to brake going downhill. I fell off. I hung on. I progressed. By lunchtime on the fourth day, John declared we were inside Gates of the Arctic National Park & Preserve — though there was no literal gate, no ranger, no need for my national park pass. It was just vast, white wilderness, mountain peaks, and an occasional sliver of blue sky. Among so many great national park experiences, this has got to rank near the top.

Dog sleds offer one way to traverse the roadless wilderness of Gates of the Arctic National Park & Preserve.

Connie SargentIt was during this trip that I learned more about the proposed Ambler Road and its potential impact. Sure, I had heard of the Ambler Road through NPCA, and I had casually read a few articles about it in the media. But it seemed like it was someplace far away, unrelated to me. To my surprise, this incredible wilderness that I had seen by dog sled was only a few miles from the proposed road.

In addition to operating the Iniakuk Lake Wilderness Lodge, John is a longtime opponent of the Ambler mining road, including serving as the Brooks Range Council Chairman. This was March 2024, and its construction seemed like a long shot to me. Indeed, one month later, the road proposal was rejected by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in response to overwhelming opposition from local communities and advocates like John.

I returned to the Brooks Range in June 2025, and everything was completely different. What had been frozen and white was now green with flowing water. We canoed across the lake, and then hiked through marshy sedge tussocks, up hills, and across the Continental Divide, with water on one side bound for the Pacific and water on the other flowing to the Arctic. The great Western Arctic caribou herd travels through this area, shedding the beautiful, bleached antlers that were scattered all around us. From the tops of the hills surrounding us, the view was an endless procession of mountain peaks and valleys, strings of lakes, and streams rushing down drainages. The sense of scale and pure wilderness, the notion of the long history of the Indigenous people who live here, and the sense of being only a visitor among other living creatures in this landscape was humbling. I was entranced all over again.

Summertime in the Brooks Range means trading a dog team for a canoe.

Connie SargentIt was also during this visit that the threats to Gates of the Arctic National Park & Preserve and the Brooks Range landscape were significantly different. On day one of the second Trump administration an executive order called for unleashing Alaska’s energy dominance. Multiple projects and landscapes were named, including the Ambler mining road. It was clear that building this 211-mile industrial mining road, which includes 26 miles situated within Gates of the Arctic National Park & Preserve, had once again become a priority.

I flew the entire proposed route of the road on my way from Gates of the Arctic to Kobuk Valley National Park. From above, I could clearly see this pristine corridor with its abundant waterways — including six wild and scenic rivers — mountains and vast landscape full of moose and bear and wildlife below me. Sadly though, I could also see initial signs of development on the landscape, as administrative actions have emboldened initial mining research. The focus on extraction versus preservation is clearly marching forward, no matter what has been agreed to in the past.

Industrial development of this corridor will come at a great cost, both in dollars and environmental degradation. The road will have to be built on melting, shifting permafrost, requiring a thick foundation of gravel and constant upkeep. And the road is just the beginning; a future industrial mining district could include multiple operations, along with significant gravel mines created just to build and service the road. The road will sever the Western Arctic caribou herd migration route, interrupting one of the longest land migrations on earth. And with an estimated 3,000 culverts and stream crossings, the migration and spawning of chum and chinook salmon, Arctic grayling, and sheefish will be impacted — even as water quality is degraded due to erosion, increased sediment, and toxic pollution from heavy metals. The food security for 60 Indigenous communities, who subsist on the landscape, will be jeopardized.

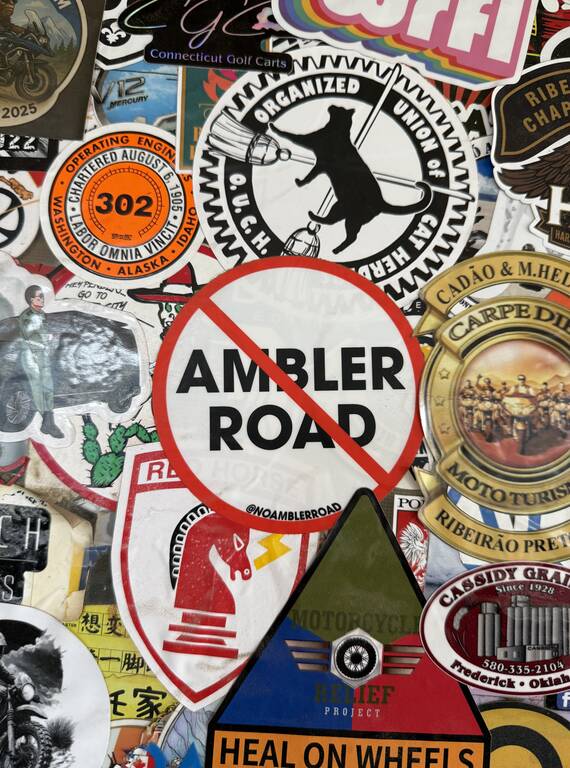

Opposition to the proposed Ambler Road has been widespread.

Connie SargentTo date, 88 Alaska Native Tribes and First Nations have formally passed resolutions opposing the Ambler Road project, and during the comment period prior to the BLM decision in 2024, 135,000 people logged comments opposed to the road. With no regard to this public opposition, politicians continue to erode the protections to the Brooks Range.

This month, the Senate followed previous action by the House of Representatives in voting to revoke the Central Yukon Resource Management Plan, originally created after over a decade of public outreach including Tribes, hunters and anglers, conservation groups, and other stakeholders to protect wildlife and landscapes on 13.3 million acres of BLM land, including those contiguous with Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve.

And in a live announcement from the White House on Oct. 6, followed by an announcement by the Department of the Interior, the Trump administration has overridden previous rulings and instead announced its approval to establish the Ambler mining road, through America’s largest national park landscape.

These actions collectively open the door further to developing Ambler Road. Bit by bit, with each congressional vote and executive order nibbling away at environmental protections, this vast wilderness — one of the last on Earth and supposedly protected by law — will be exploited and lost forever.

However, I stand with NPCA as the century-old fearless and outspoken defender of Gates of the Arctic and all of America’s national parks. Together, with our partners from across the country, we will continue to fight this with everything we have.

About the author

-

Connie Sargent NPCA Trustee

Connie Sargent NPCA TrusteeConnie Sargent is a retired business communications ESL teacher. She is now dedicating her time to exploring every National Park in the United States. She serves on NPCA’s National Council and is a member of NPCA’s Board of Trustees.

-

General

-

- NPCA Region:

- Alaska

-

Issues