Alaska is home to some of the last untamed landscapes in the country — but a proposed mining road could forever slice through part of the Brooks Range and harm two Arctic parks.

I can’t remember a time without mountains, clean water and skies a crackling blue. I was lucky enough to be raised in the Brooks Range, 60 miles north of the Arctic Circle, on the edge of Gates of the Arctic National Park. My folks built a home and a wilderness lodge from locally harvested logs, and as the years went by, we worked hard to make it a comfortable place for people far beyond Alaska to come visit.

In those early days, my crib was often in the toolshed, surrounded by chainsaws and hand-logging equipment. I chased frogs and minnows along the edge of Iniakuk Lake until I was old enough to paddle my own boat. By age 7, I was guiding fishermen from the helm of an electric trolling motor, and at age 10, I graduated to an 18-foot riverboat because I was finally big enough to pull-start an outboard.

We spent our winters in Fairbanks, Alaska’s second largest city, 200 miles south of the Brooks Range. I grew up with a foot firmly planted in two separate worlds. I liked them both, but if I ever had to choose, I would easily head for the mountains.

In Alaska’s Brooks Range, time is measured in seasons, and distance is measured in difficulty. The usual struggles against traffic, congestion, impatience and stress are gone. That’s not to say that life is easy, but priorities are different. The priority is working with the environment, not to conquer it, but to pace yourself alongside it. Cabin logs are nearly impossible to move through the dense brush and mosquitos of summer, but in winter they will slide easily along a well-packed trail of snow. A simple running water system in summer becomes a nightmare of frozen pipes in winter, so we take apart the drain lines and put a bucket under the sink. We pace ourselves, and if we do it right, it lasts for a few years. But it takes constant vigilance, patience and time.

The land, the weather, the seasons, they all bring a wide array of difficulty balanced with advantage. That balance is held in tender regard in the far north and respected. There is no animosity in our wild places. Even though it can be both illuminating and deadly, it does not single you out as a competitor.

This is changing with a recent proposal from the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority. The southern edge of the Brooks Range faces competition in the form of industrial development. This development would stretch a 220-mile road across its neck from east to west, with 20 miles disrupting the fragile ecosystem of Gates of the Arctic National Park. The road proposal would slash its way across boreal forests that thrive on shifting permafrost. It would bridge multiple wild and scenic rivers with massive beams of steel. The steel would have to span the rivers entirely, since water levels and ice are too powerful an engineering obstacle in the far north.

Beside this great slash in the land, gravel mines would gape into existence, potentially every 10 miles or less. Millions of tons of gravel would spread from the mines like butter on hot toast. As it melts into the land, more will be heaped in its place, until a wall is built wide enough to sustain industrial traffic. Beneath the wall, hundreds of culverts will attempt to let water pass underneath, but these culverts will need to be built for salmon passage, overflow, ground thaw and erosion.

The proposed road will not connect a single village. It will never carry a child to school or an elder to a hospital. It will only exist so that mountaintops can be removed and their valleys filled with mine waste. The waste will be so acidic, it must be contained in perpetuity or it will sterilize local waterways. Perpetuity is a time frame that does not exist in mining law and commercial bonding, so it is hard to imagine engineering that will economically and feasibly deal with the problem. It has never been done before.

A Billion-Dollar Driveway

A life-long resident of Alaska worries a road would destroy the wilderness he knows and loves.

See more ›The potential for disaster spans Alaska’s continental divide. The waters from the Ambler Mining District drain west, past the villages of Kobuk, Shungnak and Ambler and through Kobuk Valley National Park as they head into the Bering Sea. These waters are home to fish adapted for life in the very cold waters of the far north: sheefish, char, salmon, whitefish and burbot and the occasional seal, walrus and whale. The majority of the road proposal is on the east side of the divide, so any road pollution would flow south, past the villages of Evansville, Bettles, Allakaket and Alatna and into the Yukon River.

The idea is progress, economy, development, but it can’t happen without huge subsidies from the state of Alaska. The idea is that new technology will sidestep the disasters of the past. It will work because lobbyists say it will. It will work because Alaskan politics do not look favorably on wild lands. It will work in concert with old mining laws. Mining laws from the late 1800s with negligible taxes, inadequate bonding and a jaundiced eye toward fish, water and those other places beyond the parking lot.

The terrible irony of the current proposal is that we make the most return on the land when we leave it like it is. It is so much less expensive to manage it properly now, when the rivers are clean and full of fish. We don’t have to figure out how caribou can migrate over a 20-foot-tall road when it doesn’t exist. The wild places in Alaska become more valuable each day that they remain intact. Gates of the Arctic is widely acknowledged as the premier wilderness park in the National Park System, and visitors from across the globe travel here for adventures unlike anywhere else in the world. Alaskan resources do not need to be dug up and trucked to China. They can spawn and return in cold, clear streams. They can rut and calve by the hundreds of thousands on rolling tundra and tilting forests of black spruce.

We did not inherit this great state, we are borrowing it from the future, so we should take care of it. We should maintain our commitment to national parks. We should set a pace of development that recognizes the great value of contiguous wild places and intact ecosystems. We should do the right thing for a change.

About the author

-

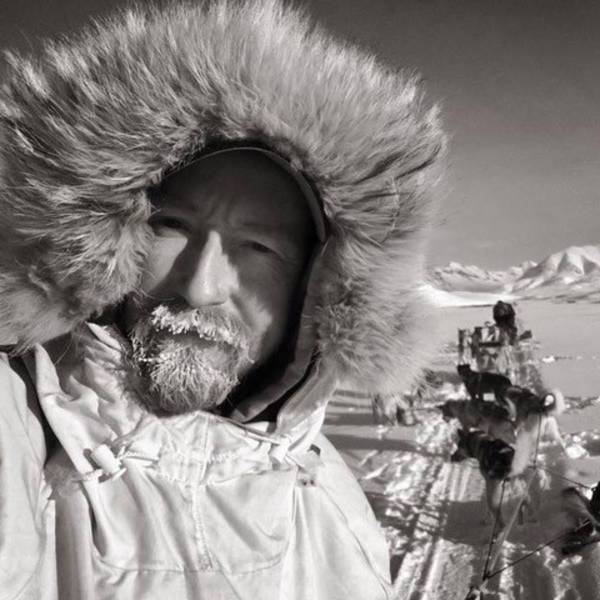

John Gaedeke Chairman of the Brooks Range Council

John Gaedeke Chairman of the Brooks Range CouncilJohn Gaedeke is a second-generation Brooks Range guide, raised at Iniakuk Lake and along the Alatna River corridor in the heart of the Brooks Range and Gates of the Arctic National Park. He spends half the year at Iniakuk Lake Wilderness Lodge guiding summer hiking, floating, fishing and flight-seeing trips as well as winter dogsled expeditions, day trips and Northern Lights viewing. The other half of the year he is a carpenter in Fairbanks.

-

General

-

- NPCA Region:

- Alaska

-

Issues