Celebrate Pride Month by learning about the not-so-hidden LGBTQ+ history at these national park sites.

For most of history, it’s been safer for LGBTQ+ people to live quietly than risk discrimination, blackmail and legal repercussions — and that means many of their stories remain hidden or lost.

Being Gay Outside

Can they see me? Am I safe? One staff member explores ways to honor queerness and make the outdoors more inclusive and welcoming for all people.

See more ›Homosexuality was illegal in all 50 states until 1962, and anti-sodomy laws remained on the books in 14 states until 2003 when Lawrence v. Texas rendered them unconstitutional. Protections for trans people to safely access healthcare, fair employment and housing remain few and far between. Roughly half of U.S. states don’t explicitly prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity for those seeking housing, public accommodations or credit. There’s still a long way to go before LGBTQ+ people enjoy full legal protections, especially as the rights we’ve already won remain under constant threat.

Every June, we commemorate this long fight during Pride Month. It’s a time to celebrate the resiliency and joy of the LGBTQ+ community and remember how hard the queer folks who came before us fought to claim space and live freely. I grew up queer and lonesome for stories of people who felt like me, loved like me, dressed like me. Every queer story I find now feels like a part of my own — without these stories, I know I’d live in a very different world. We must remember the people who fought for us and never take them for granted.

While there’s currently only one national park site explicitly dedicated to LGBTQ+ history and culture, queer individuals and communities have left their mark on every site in the national park system. Here are five stories about the LBGTQ+ community protecting and fighting for each other.

1. Fire Island National Seashore, New York

At a time when homosexuality was still illegal in Manhattan, America’s first gay and lesbian town was growing just a few hours away, off the coast of Long Island. Cherry Grove has been a queer enclave on Fire Island since at least the 1930s — a place where LGBTQ+ visitors and residents could live freely, the isolated location shielding them from unwelcome judgement and development.

The Unsung Heroines of Stonewall

More than half a century after New York City’s Stonewall Uprising, these bold women continue to inspire us. Let’s not forget who they were.

See more ›Most of the island is only accessible by boat, and during times when members of law enforcement actively discriminated against LGBTQ+ people in other parts of the state, the police presence in Cherry Grove disappeared when the last ferry departed at midnight, making way for a vibrant nightlife. Women were free to wear trousers without legal trouble (in the city you risked arrest if you wore fewer than three items of clothing deemed appropriate for your perceived gender). Raids and arrests happened, but were far less common than in mob-run gay bars in the city. Queer theater thrived, and you can still visit the Cherry Grove Community House and Theater, which is on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places — a rare landmark documenting the LGBTQ+ community before the Stonewall uprising of 1969.

In the 1960s, just as the civil rights movement was encouraging more diversity and inclusivity in “The Grove,” developers moved to build a motorway across Fire Island. This would have disrupted both the queer community and the Sunken Forest, a unique coastal ecosystem sheltered by sand dunes — one of only two like it anywhere in the world. LGBTQ+ activists rallied to protect their home and this unique ecosystem, and in 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed Fire Island National Seashore into existence, protecting 26 miles of delicate coastline, including Cherry Grove.

2. Independence National Historical Park, Pennsylvania

Four years before the Stonewall riots, protesters gathered in front of Independence Hall on July 4 to picket and remind onlookers that gay and lesbian Americans did not enjoy the same rights promised in the Declaration of Independence. The location was no coincidence: The demonstration took place right after Philadelphia’s Independence Day parade, providing a stark contrast between the celebration of freedom and an outcry against discrimination.

Untold Stories

The Park Service strives to tell the history of all Americans, but one group has gone almost entirely overlooked.

See more ›The demonstrations, called Reminder Days, took place annually for five years, organized by an alliance of lesbian, gay and bisexual activist groups around the Northeast, together called the East Coast Homophile Organizations (ECHO). In the face of rampant hiring discrimination, leaders wanted to stress employability and respectability, enforcing a strict, traditional dress code with jackets and ties for men and dresses for women. Demonstrators were told to picket single file — though in the final year, two women decided to hold hands, and many others followed suit, disrupting the strict policies set by ECHO leaders.

Though mostly ignored by the press, Reminder Days grew each year, from 39 participants in 1965 to 150 in 1969, the final year. Organizers received death threats after Stonewall, but leader Frank Kameny arranged police protection and chartered a bus to help protesters arrive safely from New York City.

In 1970, the community turned its attention to the Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade, commemorating the first anniversary of the Stonewall uprising. Annual commemorations of Stonewall eventually grew into the Pride parades and celebrations that are now common throughout the country.

3. Gateway National Recreation Area, New York and New Jersey

Jacob Riis Park, a mile-long strip in Gateway National Recreation Area, has been a haven for LGBTQ+ sunbathers and activists since the 1940s. Though at first the beach was predominantly populated by white gay men, by the 1950s and 60s the crowd was much more diverse. The park was a hub of activism even before the Stonewall uprising in 1969, and groups such as the Daughters of Bilitis hosted organizing meetings there. In 1971, the Gay Activists Alliance — an influential protest group led by former members of the Gay Liberation Front — held voter registration drives in the sand.

Though one guidebook called Riis “one of the best Gay Rivieras in the world,” the beach isn’t particularly picturesque: It sits in front of the ruins of a sanatorium for tuberculosis patients. Like other places on this list, its isolation helped it grow and thrive as a queer community, away from the often watchful and judgmental eyes of mainstream heterosexual society.

The park became part of the National Park System in 1972. The increased presence of law enforcement made it harder to sunbathe as freely, but it’s still known today as one of the gayest beaches in New York.

4. Vicksburg National Military Park, Mississippi

Though it’s impossible to know exactly how many women disguised themselves as men to fight in the Civil War — on both sides — historians’ estimates range from 400 to over 1,000. Many returned to their given lives and identities when the fighting was over, but at least one person was known to keep his name for the rest of his life.

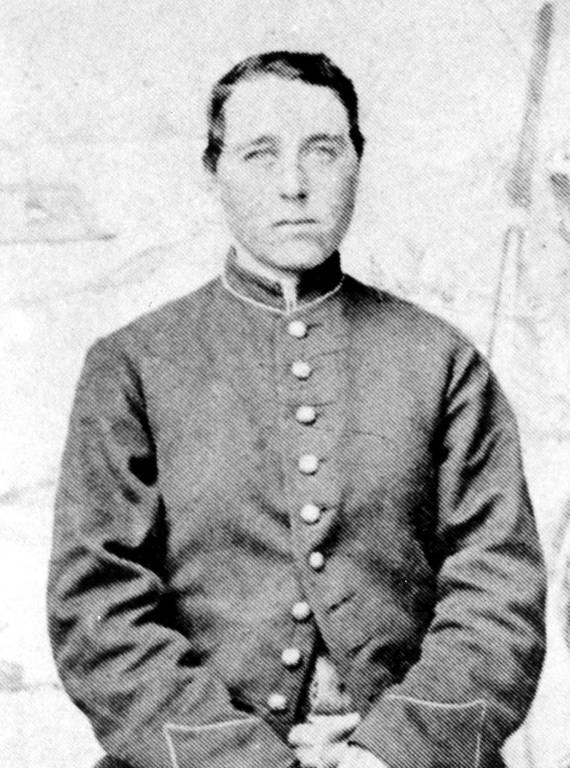

Albert Cashier, November 1864

Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and MuseumAlbert Cashier was assigned female at birth but started dressing as a boy from a young age. He grew up in Ireland and immigrated to the United States as a stowaway during his teens, living under his chosen name in Belvidere, Illinois. He enlisted in the Union army in 1861, serving in the 95th Illinois Infantry for the duration of the war. He fought in 40 engagements, including the Siege of Vicksburg, when he was captured by Confederate troops during a reconnaissance mission. He managed to escape by overpowering a guard, despite his small stature.

After the war, Cashier returned to Belvidere and worked as a farmhand, church janitor, cemetery worker and street lamplighter — all jobs generally restricted to men. He also voted in elections and claimed a veteran’s pension without raising questions for decades. Later in life, Cashier was institutionalized following the onset of dementia, and attendants discovered his secret, outing him in the press and forcing him to wear traditional women’s clothing. His former comrades were surprised yet supportive and protested his treatment even as he was investigated for fraud for claiming a military pension.

When Cashier died in 1915, his friends helped ensure he was buried in full uniform, with a tombstone that bore his military service and chosen name. Cashier’s name is also included on the Illinois Memorial at Vicksburg National Military Park, dedicated in 1906.

Though the term transgender didn’t exist during Cashier’s lifetime, scholars suggest that his story has common qualities with people who identify as transgender today.

5. Stonewall National Monument, New York

Stonewall National Monument is the only national park site dedicated exclusively to LGBTQ+ history and culture. It preserves the story of the Stonewall uprising, a watershed moment in the modern LGBTQ+ civil rights movement.

Living openly as an LGBTQ+ person was illegal or at least dangerous in most parts of the country in the 1960s — discrimination was rampant, and fear of exposure and its consequences was constant. But one night in Greenwich Village, the community had had enough. During a routine raid by police at the Stonewall Inn, patrons fought back — for six nights. The conflict garnered national attention and the gay civil rights movement took root and became more visible — and protesters grew more vehement in defending their rights.

Stay On Top of News

Our email newsletter shares the latest on parks.

Gay activist groups sprang up around the country, growing from 50 to 60 in 1969 to at least 1,500 a year later. Many of them gathered in 1970 for the first Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade, which we now celebrate annually with Pride marches around the country.

Though often overlooked by history, trans women of color were at the center of the uprising and the ensuing revolution. In 2016, President Barack Obama designated Stonewall as a national monument, ensuring its legacy remains part of the American story — but the work doesn’t end here. Proper funding would help tell the full story of Stonewall, through adequate staffing to interpret this critical moment in modern civil rights history.

About the author

-

Vanessa Pius Former Senior Manager, Social Media and Engagement

Vanessa Pius Former Senior Manager, Social Media and EngagementAs Senior Manager, Social Media and Engagement, Vanessa advanced NPCA’s mission through creative storytelling and engaging the organization’s online community until 2025.