Birmingham was once the nation’s most segregated city, home to brutal, racially motivated violence. Today, a new national park site commemorates the critical civil rights history that happened here.

Last October, I was headed to Birmingham, Alabama, and my mother was worried.

Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument Will Preserve Pivotal Sites from America’s Civil Rights History

In the 1960s, Birmingham, Alabama, was one of the most segregated places in the United States. Nonviolent protesters suffered brutal mistreatment in the struggle for equality and ultimately changed the…

See more ›The secretary of the Department of the Interior and the director of the National Park Service were attending a public meeting at the city’s 16th Street Baptist Church. Their mission was to hear from residents whether they wanted a new national park site commemorating Birmingham’s civil rights history. And it’s that history that had my mother so concerned, because for her, the word Birmingham triggers sharp memories of a time when that part of the American South was the worst of bad places for black people. She worried for her son that what’s past may be prologue.

Eight years ago, the country elected its first African American president. Segregation, Jim Crow and the violence inspired by those two great national evils have largely dissipated. The Birmingham I know is home to great barbecue, friendly people and downtown sidewalks that tend to roll up on weekdays at 4 p.m. But my mother remembers Birmingham as it was in the decades before I was born. When segregationist, state-sanctioned terrorism was commonly used to enforce a vicious brand of apartheid, and few African Americans felt truly safe in that city. The night before I headed to Alabama, my mother’s last admonition before she hung up was a plea.

“Please be careful,” she told me.

Birmingham in the 1950s and 60s was known as the most segregated city in the United States. Jim Crow laws separated black and white people in parks, pools and elevators, at drinking fountains and lunch counters. African Americans were barred from working at the same downtown businesses where many of them shopped. Ordinances even outlawed blacks and whites from competing against each other on the same field during sporting events. At the heart of such strict segregation policies was the belief by some whites in the inherent inferiority of black people and the dangers associated with “race mixing.”

That inequality sparked resistance in the African American community, which in turn drew the wrath of Alabama’s pro-segregationist leadership. Those who dared to advocate for change were subject to harassment, job loss, beatings and arrest.

And then there were the bombings. Between 1945 and 1963, there were 60 bombings of black homes, churches and businesses in Birmingham, all designed to intimidate or kill blacks who had the audacity to fight for basic human rights. Bombingham was what my mother’s generation called that city.

In January of 1963, Alabama Governor George Wallace doubled down on the state’s pro-segregationist philosophy. He declared in his inaugural address that, “In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod the earth” — his description for white people — he would defend Alabama against any efforts to integrate. “Segregation today … segregation tomorrow … segregation forever” was the way he famously described his views on race.

In the wake of the governor’s pledge to defend segregation against all comers, civil rights leaders Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., decided to target Birmingham. Project C (C stood for confrontation) was the nonviolent, direct-action campaign they designed to break the back of segregation in that city. Comprised of marches and boycotts, Project C counted on a violent reaction by the city’s leadership. Shuttlesworth and King gambled that civil rights protesters marching in the streets, boycotting downtown businesses, and filling the city’s courts and jails would overwhelm Birmingham’s resources and force its leadership to make concessions.

See Where History Happened

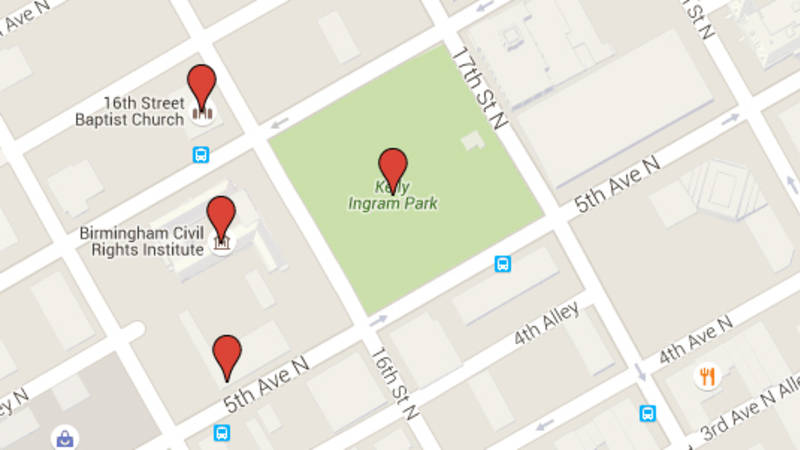

A map of four of the key sites that could be become part of the proposed Birmingham Civil Rights National Historical Park.

See more ›While Shuttlesworth organized from Bethel Baptist Church, King set up a war room at the A.G. Gaston Motel. The Gaston was located one block south of the 16th Street Baptist Church and close to the heart of Birmingham’s black business district. Kelly Ingram Park, a large open space about the size of a city block, was adjacent to both the church and the motel.

The Project C protest marches began in April 1963. Protesters gathered at 16th Street Baptist Church and Kelly Ingram Park, intent on marching east into downtown Birmingham. From the start, Eugene “Bull” Connor, Birmingham’s ironically titled commissioner of public safety, deployed both the police and fire departments to brutally break up the marches.

Nonviolent demonstrators were beaten with police nightsticks and bitten by police dogs. The fire department sprayed marchers with water from high-powered cannons that had sufficient force to strip bricks from buildings. Those who weren’t immediately bowled over were pinned against the sides of buildings as pressurized water pounded mercilessly against their bodies. After the adults had been arrested en masse, high school and elementary school students led a Children’s Crusade in another march for freedom and justice. City authorities chose to handle the young equally as roughly as their parents and older siblings.

The world watched as events unfolded in Birmingham in 1963. And when people saw the lengths to which some would go to win freedom and justice and the extent to which others would attempt to deny them those rights, attitudes began to change. In May, under intense public pressure, Birmingham’s leaders came to the Gaston Motel to negotiate an end to the Project C protests, ultimately agreeing to end some Jim Crow practices.

History, unfortunately, is rarely a linear march from bad to good. In Birmingham it took one more bomb blast, this one on September 15, 1963, claiming the lives of four African American girls who were preparing for Sunday church services at 16th Street Baptist Church, to galvanize the nation into passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

At the October 2016 public meeting, Birmingham residents offered powerful testimony in support of the civil rights park in their city. Rep. Terri Sewell (D-AL) declared that to delay the designation would be to deny justice to all those who fought for equality and have worked tirelessly for decades to preserve Birmingham’s history.

The most poignant statements came from the aging veterans of Project C — the foot soldiers whose fight against racism and inequality in the 1950s and 60s enabled all of us to sit confidently in 16th Street Baptist Church without fear of violence or retaliation. Even the Birmingham Fire Department attended with a diverse coalition of firefighters determined more than 50 years later to show just how far the city and the nation have come. They too wanted a civil rights park in Birmingham.

It is easy to think that the Birmingham story is a key component of our American narrative so strongly etched into the American consciousness that it will never fade. But time and progress have their ways of shading over the significance of events and people, requiring that we become more deliberate in preserving our shared past.

Stay On Top of News

Our email newsletter shares the latest on parks.

Thanks to the authority of the Antiquities Act, any president can protect significant places by designating them as national monuments. Now, with the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, Birmingham’s civil rights history is protected in perpetuity for the world to see. And with this new park site, we ensure that the past is less a prologue than a mile marker demonstrating how far we as a people may go when the better angels of our nature prevail.

About the author

-

Alan Spears Senior Director of Cultural Resources, Government Affairs

Alan Spears Senior Director of Cultural Resources, Government AffairsAlan joined NPCA in 1999 and is currently the Senior Director of Cultural Resources in the Government Affairs department. He serves as NPCA's resident historian and cultural resources expert. Alan is the only staff person to ever be rescued from a tidal marsh by a Park Police helicopter.

-

General

-

- NPCA Region:

- Southeast

-

Issues