Summer 2022

Troubled Waters

For decades, biologists and anglers stocked national parks with nonnative trout. What will it take to undo the ecological damage?

In 2009, shortly after graduating college, I packed up my Corolla, drove from New York to Yellowstone, and, under the tutelage of the National Park Service, learned to kill.

I’d signed up that year to work for Yellowstone National Park’s Native Fish Conservation Program, a division tasked with restoring the park’s native cutthroat trout, a gold-flanked fish so named for the vivid crimson slash beneath its jaw. Cutthroat have inhabited Yellowstone since its glaciers receded 10,000 years ago, and they’re as integral to the park’s fabric as bison or bears. Just as Yellowstone has long sheltered threatened grizzlies, so too is the park an aquatic refuge for sensitive trout imperiled elsewhere by overgrazing, mining, development and climate change.

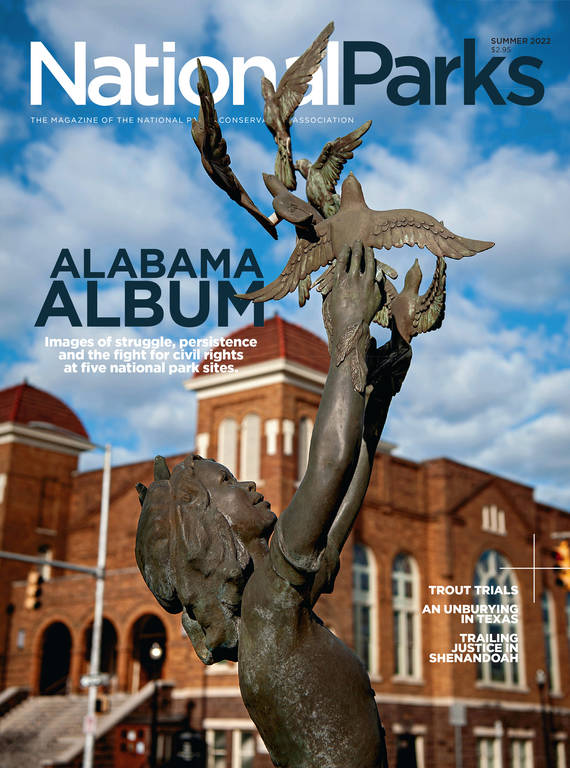

Recreational fishing has a long history in Yellowstone. This photograph was taken in 1923.

NPSEven within Yellowstone, however, cutthroat are beleaguered, due partly to the Park Service’s own historic actions. Between the 1880s and the 1950s, Yellowstone’s managers, determined to turn America’s first national park into a fisherman’s paradise, planted 300 million trout in its waters — millions of them members of nonnative species — with ruinous consequences. Feisty eastern brook trout outcompeted cutthroat, voracious European brown trout preyed on young native fish, and rainbow trout likely originating from California bred with cutthroat to produce hybrid “cutbows.” And, decades later, one or several anonymous anglers illegally released lake trout into Yellowstone Lake — an event that rippled through the park nearly as dramatically as the reintroduction of wolves.

I was, that summer, a humble intern, paid an AmeriCorps pittance and housed in a ramshackle trailer, a cog in the agency’s multimillion-dollar fish restoration machine. I learned various death-dealing techniques that took me to spectacular corners of the park’s immense backcountry. Our crew hiked up Specimen Creek to poison cutbows and restock genetically pure cutthroat. We traipsed along Soda Butte Creek with backpack shockers — devices that run electric currents through the water and stun any fish within their field — to eliminate brook trout. We bounced over Yellowstone Lake in skiffs, setting nets to ensnare the lake trout teeming in its depths. My lowly employment status didn’t make the work any less thrilling, nor did it deflate my sense of purpose. “The entire ecosystem of the most iconic national park in America is in jeopardy,” I wrote on the blog I kept that summer.

Although it’s tempting to chalk up that statement to youthful hyperbole, it wasn’t an exaggeration. Aquatic invasive species dominate national parks; one 2010 report identified 361 water-dwelling invaders in or near 129 parks. And while many of these interlopers, such as zebra mussels and silver carp, were introduced accidentally, some of the most problematic are trout, deliberately stocked during an era when servicing tourists, not protecting ecosystems, was the Park Service’s paramount goal. According to the 2010 report, nonnative rainbow trout inhabit around 90 park watersheds, brown trout nearly 80, and brook trout close to 40 — almost surely a considerable underestimate of the problem, given that invasions can simmer undetected for decades.

From the get-go, fish planting in national parks was conducted with little oversight: Early stockers, wrote a Park Service biologist in the 1960s, conveyed trout to remote lakes in “coffee pots.” But while much of the stocking was slapdash, its consequences were lasting. In the Grand Canyon, stocked trout gulped down native suckers and chubs, contributing to their endangerment. And in the high lakes that freckle Washington state’s North Cascades National Park, fish ravaged frogs and salamanders. The introduction of trout, said John Wullschleger, head of the Park Service’s fish program, “probably extirpated some native species before we even knew they existed.”

Over the last several decades, many parks have attempted to mitigate this outsize damage, taking decisive action to remove introduced fish and restore native species. Yet in its war against aquatic invaders, the Park Service is winning on some fronts but locked in stalemate on others. Compared to many terrestrial animals, fish, concealed by the opacity of water, are hard to study and harder still to eliminate. In one Rocky Mountain National Park stream, for instance, biologists attempted to poison nonnative trout — only to discover that the fish’s eggs survived the treatment, buried deep within creek-bed gravel. What’s more, new invasions continue to pop up: In the last three years alone, nonnative cisco and smallmouth bass have infiltrated Yellowstone’s watershed. And despite the ecological detriments of nonnative fish, angling remains a powerful cultural and economic force that occasionally confounds science-based management. More than 130 years after stocking began in Yellowstone, the mistakes of our predecessors remain hard to undo.

William Gladstone Steel inched down the vertiginous face of Crater Lake’s caldera, a bucket clenched in his hand. Water sloshed within, and Steel paused to wipe his brow and check his cargo. He was surely anxious: It was August 1888, and a park’s future depended upon his success.

Steel, then in his mid-30s, was fulfilling a longstanding dream. A journalist and mail carrier, he’d been obsessed with Oregon’s Crater Lake since youth, when he reportedly read about its surreal beauty in the newspaper he used to wrap his lunch. He became the foremost advocate for the lake’s conservation, only to watch loggers and ranchers block his attempts to protect it. So Steel decided to stock Crater Lake with trout. If he could turn the fishless lake into a wonderland for anglers, he reasoned, its constituency would expand. He would save Crater Lake by transforming it.

Steel secured hundreds of rainbow-trout fry from the Rogue River, 45 miles from Crater Lake. Then he set out by wagon, stopping at creeks to refresh the trout’s water. When the rutted road threatened to upset his bucket, he walked the last leg. By the time Steel arrived, nearly all of his trout had gone belly up. Still, he hiked down to Crater Lake’s shore and freed the 37 survivors. Almost miraculously, Steel’s transplants flourished, and in 1901, a reporter noted that the lake held “cold-water trout, some of which are 30 inches in length.” Crater Lake National Park was created a year later.

Steel’s operation, quixotic as it sounds, was part of a grand tradition of aquatic meddling. John Muir cheered Yosemite’s fish stockers, a hodgepodge of angling clubs and government officials who hauled trout into the Sierra Nevada by foot and mule. “Soon, it would seem, all the streams of the range will be enriched by these lively fish, and will become the means of drawing thousands of visitors into the mountains,” Muir rejoiced. In Montana’s Glacier National Park, the Great Northern Railway planted brook, rainbow and cutthroat trout to entice tourists to its trains and chalets. Yosemite’s lakes and streams were eventually stocked by airplane, while federal managers poured rainbow and brown trout into the Grand Canyon. By 1962, rangers deemed Bright Angel Creek, a once-troutless tributary of the Colorado River, “the best trout stream in the state of Arizona.”

As fish stocking intensified, so did its repercussions. In 1924, the biologist Joseph Grinnell observed that Yosemite’s native amphibians vanished wherever hungry trout were planted. “It seems probable that the fish prey upon the tadpoles, so that few or none of the latter are able to reach the stage at which they transform” into frogs, Grinnell wrote. Others voiced similar concerns. “So general has been the thoughtless, unscientific planting, I should say ‘dumping’ of [nonnative] fish in nearly all waters,” lamented David Madsen, the Park Service’s supervisor of fish resources, in 1937, “that not even the waters of the national parks have escaped.”

Even Steel’s masterstroke backfired. In 1915, afraid his precious trout were starving, he dumped 15,000 nonnative crayfish into Crater Lake — a bid to feed one introduced species with another. But the trout ignored the crayfish, which in turn preyed upon the Mazama newt, an amphibian that dwells only within Crater Lake. Biologists later found that crayfish had colonized nearly 80% of the lakeshore and could drive the endemic newt “perhaps to extinction.”

In some ways, the Park Service’s fish dilemma reflects its own contradictory origins: The Organic Act, the 1916 legislation that created the agency, enjoined it both to conserve the “wild life” within parks and “provide for the enjoyment” of visitors. At first, angler enjoyment was the priority, but over time the Park Service began to emphasize the conservation side of its mission. Yellowstone ceased stocking in 1959, and, a year later, the agency’s top aquatic biologist deemed “put-and-take” stocking — dumping fish so that anglers could immediately catch and eat them — “not compatible with the fundamental objectives” of the Park Service. The shift accelerated in 1963, when conservationist A. Starker Leopold and colleagues published a report declaring that “maintenance of naturalness,” not visitor entertainment, should be parks’ primary goal. Although Leopold’s report didn’t explicitly address trout, it drove park managers to take a renewed interest in restoring the aquatic ecosystems in their care. Many parks cut back on stocking or ceased altogether.

Angling for Cash

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area tries a novel approach to control brown trout.

See more ›This pivot wasn’t universally embraced. When, in 1985, North Cascades proposed to stop stocking trout in alpine lakes, fishing clubs rebelled. The outraged anglers were backed by the Washington State Department of Game, which earned revenue from fishing license sales and asserted that animals in national parks fell under its own jurisdiction. The state even threatened to dispatch a helicopter to “bomb” lakes with trout.

The acrimony reflected a hoary dispute about what parks were for: human pleasure or ecological preservation. At one meeting, recalled Jon Jarvis, then North Cascades’ chief of resources, a state biologist described high lakes as cornfields: “You put in some seed, you give it some fertilizer, and within a season, you can harvest.” The federal and state agencies eventually ran a research program to study the situation and identified some lakes where nonnative fish should be actively removed, some where they’d be allowed to die out over time, and some where stocking would continue. In 2014, Congress settled the dispute by authorizing trout planting (a move that NPCA opposed) in 42 of the park’s 500-odd lakes, including some in designated wilderness. “The Park Service is in the perpetuity business,” said Jarvis, who by then was the agency’s chief, “and sometimes you have to be willing to compromise in the short term.”

While stocking has continued in North Cascades, many parks have taken aggressive steps to reverse historical damage. In 2001, Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks in California launched an ambitious plan to eliminate fish from a number of high lakes, where nonnative trout had endangered two mountain yellow-legged frog species. Crews of biological technicians drifted out in float tubes to string up gill nets in infested lakes, then picked them free of dead rainbow and brook trout. All told, the parks plan to expunge trout from 110 lakes and 35 stream-miles by mid-century, primarily with nets and electrofishers and the select use of a piscicide, a chemical that targets fish and leaves mammals, birds and adult amphibians unharmed. “It’s basically a 50-year effort that we’re 20 years into now,” said Danny Boiano, the parks’ supervisory ecologist.

Crater Lake in Oregon was originally fishless, but the lake became a prime destination for anglers after it was stocked with rainbow trout starting in the late 19th century.

©JUSTIN BAILIEThe effort has already produced spectacular results: Where fish have come out, ecosystems have surged back to life. Boiano cites one network of lakes and creeks south of Muir Pass where the parks eradicated trout in the mid-2000s. “The frog population just exploded,” Boiano said. “Every step along the shore, 10 frogs would jump off, and hundreds of tadpoles would scatter.” Clark’s nutcrackers, Brewer’s blackbirds, water shrews and weasels flocked to the area to pick off tadpoles and frogs. Mayflies, their larvae safe from predatory trout, hatched in thick clouds that attracted flocks of gray-crowned rosy finches. And while disease subsequently ravaged yellow-legged frogs, it’s no coincidence that the lakes that retained frogs are those that Boiano’s crews cleared of trout.

“If we had not done the fish removals, the much smaller, remnant frog populations would have had a much harder time trying to withstand the fungus,” Boiano said.

Other projects proved equally effective. Take Bright Angel Creek, where stocked rainbows and browns devastated endemic Colorado River fishes such as bluehead suckers and humpback chub. In 2010, Grand Canyon National Park redoubled efforts to purge Bright Angel of its invaders. Biologists scoured the stream with backpack shockers, scooped up stunned fish, released the natives and euthanized the trout. They also erected weirs to prevent spawning trout from entering the creek. By 2018, they’d killed around 50,000 nonnatives, and populations of suckers and dace had surged nearly fivefold.

“It confirmed how much impact those trout could have,” said Brian Healy, Grand Canyon’s fisheries program manager. “It’s a real success story.”

Not every fish-control initiative pays such swift dividends — a reality that, in Yellowstone, I would learn firsthand.

Yellowstone’s fisheries program was upended on July 30, 1994, the day that a young angler hauled a long, silvery, white-speckled fish out of Yellowstone Lake. The creature was a lake trout, a species widespread in places such as Canada and the Great Lakes but nonnative to the Yellowstone ecosystem. Lake trout were not entirely strangers to the park, having been planted in Lewis and Shoshone lakes by the U.S. Fish Commission in 1890, with fairly minor ecological effects. Their introduction to Yellowstone Lake, however, wasn’t the product of an official stocking, but an unauthorized release. The unknown vandals, who’d dumped the fish sometime in the 1980s, were likely trying to create an angling opportunity, not sabotage an ecosystem, but the outcome was disastrous. By 1998, lake trout — which can weigh up to 50 pounds, many times more than cutthroat — were devouring up to 4 million native trout every year.

The collapse of cutthroat transformed the park. For millennia, cutthroat had migrated up Yellowstone Lake’s tributaries to spawn, feeding bears, otters, eagles and other critters along the way. But lake trout, true to their name, spawned on the lake floor, where bears and birds couldn’t catch them. Deprived of their cutthroat buffet, grizzlies increasingly snatched up elk calves, while eagles killed loons and trumpeter swan cygnets. Ospreys all but vanished from the lakeshore. The invasion severed the link between Yellowstone’s waters and landscapes, unraveling both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems.

The Park Service moved quickly to confront the crisis. Soon after lake trout were detected, the agency began setting gill nets to ensnare them. (Lake trout congregate in deeper water than cutthroat, which makes it possible to catch one without accidentally killing the other.) During my summer in Yellowstone, I spent many days hauling mesh and disentangling lake trout. Most were modest subadults, just a foot long, but occasionally we dredged up 20-pound lunkers as thick as my thigh. I had a grudging admiration for our adversaries, with their torpedo bodies and toothy jaws. Some emerged long-dead and slimy; others disgorged baby cutthroat like hairballs. We clubbed the live ones and dumped them back into the lake.

At the time, I confess, the project felt futile. By the time I arrived in Yellowstone, the Park Service had been killing lake trout for more than a decade, yet every day the nets came up full. The lake was too vast; we were too few. Between 1998 and 2012, despite the Park Service’s efforts, the lake trout population grew sixfold, to nearly 800,000. The agency wasn’t just losing — it was being routed.

Over time, though, its labors paid off. The Park Service and its partners implanted live lake trout with tracking devices and followed them to their spawning grounds, where biologists fried eggs with electroshocking devices, vacuumed them up with suction hoses or smothered them with organic pellets that suck oxygen from the water as they break down. The agency also hired a private fishing company, which set longer nets in serpentine patterns that targeted the largest fish. By the end of 2021, the Park Service and its contractors had killed more than 4 million lake trout.

As the lake trout population plateaued and then declined, cutthroat rebounded. In July 2019, Todd Koel, the director of Yellowstone’s Native Fish Conservation Program, ventured into the backcountry south of Yellowstone Lake, where, to his delight, he found the creeks teeming with spawning cutthroat. “It was unbelievable,” Koel recalled. “They were like salmon, their redds” — gravel nests — “all stacked up on top of each other.” Birds, bears and anglers all plied the streams. “The lake trout program has returned that whole fishery to the backcountry,” Koel said.

The Park Service is in the perpetuity business, and sometimes you have to be willing to compromise in the short term.

Yet Koel acknowledges that Yellowstone Lake is far from recovered, and the invaders have proved more tenacious than anyone anticipated. “We used to think the lake trout population was going to abruptly crash someday,” Koel said. “But it’s more like a long glide path downward, like an airplane slowly landing.” That means that some lake trout suppression must continue indefinitely. “If we took even a single year off from gill netting, we’d undo years of progress,” Koel said.

On other fronts, however, Yellowstone is decisively winning its battle against nonnatives — most notably in the Gibbon River watershed. Like 40% of Yellowstone’s waters, the upper Gibbon was naturally fishless, blocked off by a steep waterfall, until park managers introduced nonnative rainbow trout in 1889. In September 2017, the Park Service set out to rectify that mistake. The agency dispatched 35 staffers to disperse Rotenone, a piscicide, throughout 10 miles of the Gibbon and the lakes that feed it, a herculean undertaking that required helicopters to airlift more than 75,000 pounds of gear, chemicals and boats — one of which, an inflatable raft, was punctured overnight by a sow grizzly and her cub. After the toxin trickled through the drainage, biologists deactivated it with a chemical counteragent and poured in tens of thousands of cutthroat and native grayling to feed resident loons and osprey.

A park employee grinds up lake trout that have been caught on Yellowstone Lake.

JACOB W. FRANK/NPSAn intern with the Student Conservation Association holds a lake trout removed from Yellowstone waters. Lake trout in the area can weigh up to 50 pounds.

NPSThis represented a stark departure from the Park Service’s usual approach. Once, said Brian Ertel, a Park Service fisheries biologist, the park might have left the upper Gibbon fishless, thus restoring it to its pre-colonial status. But as climate change heats up streams, the river’s chilly flows could provide a refuge for cold-loving cutthroat. And because the upper Gibbon lacks sensitive amphibians, there’s little chance of doing harm by inserting cutthroat. “Now one of the first things we look at before we do a restoration project is whether this is going to be sustainable for native fish in 2040 and 2080,” Ertel said. A century ago, stocking trout wreaked havoc on park ecosystems. Today, it may ensure the persistence of a species.

Since the advent of national parks, managers have treated fish as categorically different from other organisms. When, in 1894, Congress protected Yellowstone’s birds and mammals, it explicitly permitted fishing. Jarvis, the former Park Service director, is fond of posing a question: What is the one park denizen that you can kill and eat? “You couldn’t do it to a butterfly, you couldn’t do it to a lizard, but you could do it to a fish,” Jarvis said.

The author holding a cutthroat trout in Yellowstone in 2014.

©GEOFFREY GILLERThis is, perhaps, because fish — silent, cold-blooded, expressionless — don’t activate our sympathies like eagles or elk. But it’s also true that the economics of recreational angling exert powerful pressure. (The trout fishery upstream of Grand Canyon National Park, for instance, is worth nearly $3 million per year.) I’m not immune to the joys of wetting a line in a natural temple: I’ve caught nonnative fish in Yellowstone, Glacier, Yosemite and Olympic, to name a few, and had a blast doing it. Still, whenever I behold a dazzling rainbow trout in one of these sancta, I have to remind myself that my pleasure comes with environmental costs — and that angling continues to influence parks’ aquatic ecosystems.

I was reminded of the complexity of fisheries management in 2009, as my summer in Yellowstone turned to fall and brown trout began to spawn in the Madison River. Every sundown for a week, our crew launched a raft into the Madison and spent the frigid night bobbing through the park, pumping electric currents through deep pools as snow danced in our headlights. Brown trout, temporarily stunned, boiled to the surface — hook-jawed, butter-yellow beauties as long as baseball bats. I frantically swung a dip-net through the churn and dropped the fish into a live well. When we’d landed a good haul, Ertel rowed us ashore to measure and weigh our catch, our hands cramping into claws in the icy water. One night we nearly bumped into a moose in the shallows, his stilted body looming out of the blackness like a planet in deep space.

In retrospect, I didn’t fully appreciate the irony of that Madison River research. Brown trout are a European species, and their introduction to the Madison in 1889 had done substantial harm to native fish. Yet we weren’t killing them, merely studying and releasing them. That’s because the Madison River’s brown trout fishery, both within the park and beyond it, is a legendary institution; one Montana angling site describes the fall run as “the most anticipated event of the year.” Few thrills are as intoxicating as the sledgehammer bite of an angry brown, and whether these gorgeous beings “belong” in a river doesn’t cross my mind when I’m cradling one in my net.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Most conservation-minded anglers, I think, hold ambivalent feelings about nonnative fish: affection, guilt, compassion. No doubt it’s vital that park managers ameliorate the damage inflicted by stocked trout. But as societal values change — as we become more attuned to the well-being of animals that we once considered automatons — trout welfare might also become a consideration. In countries such as Australia, the so-called compassionate conservation movement has urged ecologists to show empathy for feral cats and other invasives, and at least one American commercial fishing company now takes pains to ethically euthanize its catch. Invasive fish don’t know they’re in the wrong place, and they surely suffer when they’re poisoned and netted; I felt no small amount of discomfort watching cutbows writhe in streams that we dosed with Rotenone. How do we weigh ecological restoration against the humane treatment of individual animals?

Today, when I reread my blog, I’m ashamed by my eagerness to cast aspersions on amoral organisms. Lake trout, I wrote, seemed to have “a certain willful malignancy in their soulless eyes.” If I could communicate with my 22-year-old self, I’d tell him this: Our enemies aren’t the fish themselves, but the legacies of past generations of managers, biologists and anglers, who acted with good intentions but limited knowledge. We are, as ever, at war with ourselves.

About the author

-

Ben Goldfarb Author

Ben Goldfarb AuthorBen Goldfarb is the author of "Crossings: How Road Ecology is Shaping the Future of Our Planet" and “Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter.”