Summer 2022

Trailing Justice

A double murder in Shenandoah and writer Kathryn Miles’ search for the truth.

As dusk deepened to night on June 1, 1996, a pair of Shenandoah National Park rangers spied a blue and yellow tent hemmed in by foliage along the Bridle Trail. They approached, calling out the names of the two women they were desperate to find.

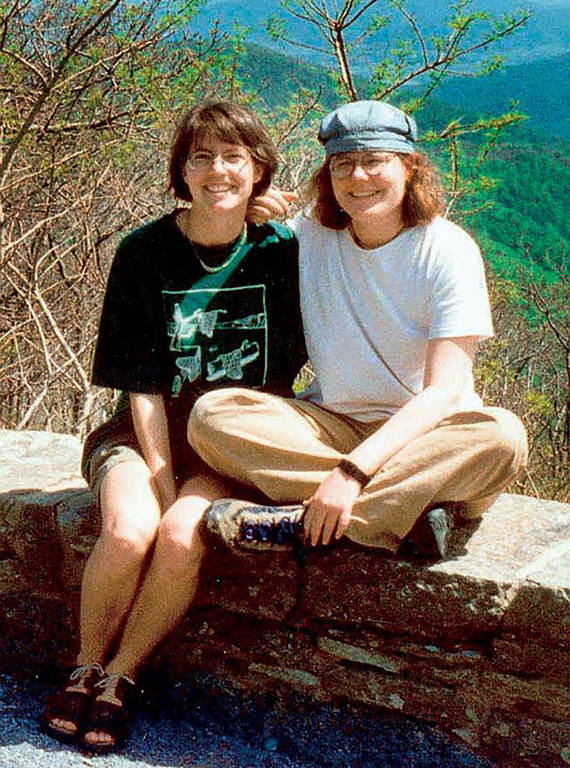

Shortly after arriving in Shenandoah in May of 1996, Julie Williams (left) and Lollie Winans posed for this picture.

FBIJulianne “Julie” Williams, 24, and Laura “Lollie” Winans, 26, had arrived in the park with Winans’ dog, Taj, on May 19. The women, both skilled outdoor guides with dozens of wilderness trips to their names, had planned to spend a week hiking and taking in the views from the trails that branch like veins from the park’s scenic Skyline Drive. But when Williams failed to return to her apartment in Richmond, Vermont, as intended, her father notified the park, spurring a two-day search.

The rangers who finally located the couple’s campsite stepped into a nightmare: The women had been brutally murdered.

Although a suspect was quickly identified and an indictment handed down in April 2002, the case had holes. The Department of Justice quietly dropped the charges in 2004, and the world — for the most part — moved on.

Two decades after the murders, journalist Kathryn Miles spotted an FBI press statement exhorting the public to submit relevant information in the case. Thinking it would be a simple feature, Miles approached her then-editor at Outside magazine about covering the story. “As soon as I got involved in the case, I realized that nothing about it was clean-cut,” she said.

Miles’ relentless reporting spanned more than five years and involved hundreds of interviews with agents, rangers, family members and experts. She also combed through thousands of pages of evidence, made countless trips to Virginia from her home in Maine, set up a half-cocked — if well-intentioned — decomposition experiment in her garden, studied other serial murders in the area, and eventually collaborated with the Innocence Project at the University of Virginia School of Law. Her efforts not only illuminated the difficulties inherent in investigating a backcountry crime scene, they also exposed a world of jurisdictional squabbles, agency underfunding, lab backlogs, unreliable witnesses and crippling confirmation bias.

Miles’ book, “TRAILED: One Woman’s Quest to Solve the Shenandoah Murders,” which was released in May, recounts the fits and starts of her research and puts forth a plausible new suspect in the horrific crime. In the excerpt that follows, the writer describes her first visit to the women’s final campsite in March of 2017.

—Katherine DeGroff

About an hour after we departed the FBI Richmond field office, we arrived at a multiuse office building on the outskirts of Charlottesville. Inside, placards for medical labs and child support enforcement offices directed visitors to the various floors. We headed, instead, to a cramped office space, where Jane Collins, who has served as the lead FBI agent in Julie and Lollie’s case since early 2000, greeted us with a Diet Coke in one hand and the handle of a small wheeled suitcase in the other. With her salon-perfect blond hair, pink nail polish and skinny jeans, Jane was a far cry from the central-casting cliche. The only thing giving her away as an FBI agent was the pistol holstered at her hip. We said our hellos and agreed that we’d follow her to Shenandoah.

Once inside the park, our little caravan was joined by a cadre of park rangers. Among them was Tim Alley, 57, the original lead law enforcement ranger in the case. Now retired and working as a private detective, Alley was dressed that day in cargo pants and a navy blue fleece pullover commemorating the 75th anniversary of the park. With his thick goatee, close-cropped gray hair and reflective Ray-Ban sunglasses pushed back on the top of his head, he looked as much like a high school football coach as he did a longtime law enforcement ranger — a persona further enforced by his gruff colloquialisms. Within just a few minutes of chatting, he was referring to the National Park Service as the “park circus” and Lollie and Julie as “our girls.” I liked him right away.

The group of us briefly consulted maps, and then our caravan, now five vehicles long, made its way northward on the park’s fabled Skyline Drive toward Skyland. The park’s largest and most well-known lodging complex, Skyland includes dozens of free-standing cabins and blocks of rooms and suites, along with conference buildings, an amphitheater, horse stables and housing for about 65 staff members (mostly dishwashers, cooks and waitstaff, but also groundskeepers, stable hands and maintenance workers). The Appalachian Trail crosses right through the 27-acre property, making it a favorite stop for backpackers.

At the center of it all sits the Skyland lodge itself, a sleek stone and wood building with panorama windows and sweeping views of the valley. On a summer weekend, the place is hectic: There’s a coffee bar with takeaway sandwiches and salads; the main dining area often has wait times of well over an hour. The pub, which opens in the late afternoon, hops with live music on the weekends. And then there are the restrooms with rows and rows of stalls, and the gift shop and plush couches and coffee tables stacked with oversized books dedicated to the park.

It took a place we all loved and filled it with horror.

In the summer and fall, Skyland can feel as crowded as any major airport; however, few visitors venture to the park in early spring, when snow is still common and the trees bare. The lodge is shuttered until late March or April, as are most of the other amenities here. So it was no real surprise that the Stony Man parking lot, located just north of Skyland at mile 41.7 on Skyline Drive, was empty when we arrived. We parked, and once outside our vehicles, the group seemed somber, standing in a tight circle, making small talk about the weather.

A few minutes later, we left the parking lot on foot, crossed Skyline Drive, and then descended down the remnants of the Bridle Trail. If I’d been alone, I doubt I ever would have found the overgrown path: Even without the camouflaging effect of summer foliage, the trailhead was all but invisible.

Walking beside me was Tim Alley, who was quick to note that he’d heard I live in Maine. He told me he grew up on a small island there, and within just a few minutes we’d found a handful of shared acquaintances, including his first cousin, whom I had first met when we were both competing in a trail marathon. Tim graduated from the University of Maine in 1980 and immediately began his career as a park ranger. In 1986, he was one of the law enforcement rangers working on the Park Service’s Colonial Parkway, which connects historic Jamestown, Williamsburg and Yorktown in eastern Virginia. That same year, Cathleen Thomas and Rebecca Dowski, a young lesbian couple, were found in Cathleen’s car, just off the parkway. Both women’s throats had been slit. The impact of working that case, Tim told me, had left an indelible mark. “The whole crime investigation thing was relatively new for all of us,” he said. “We were still trying to find our way.” The mere presence of law enforcement rangers, he continued, was something the Park Service was still very much trying to get used to by the time Lollie and Julie were killed.

It wasn’t until the late 1970s that the Department of the Interior began distinguishing between two types of rangers: interpretive, who are responsible for programming and education, and law enforcement, who are cops with all the powers of state police officers. It took another 20 years to establish hiring and training rules for the latter. Even today, most visitors to national parks don’t realize that rangers have different specialties. That lack of understanding creates all kinds of public confusion — and ultimately adds to the perils of the job, already considered one of the most dangerous in all of law enforcement. Between 1990 and 2020, eight FBI agents and six park rangers were killed in the line of duty, a staggering number when you consider that FBI agents outnumber rangers 10 to one.

The rangers walking alongside us on the Bridle Trail that day agreed that the murders of Julie and Lollie only intensified concerns for their own safety. “The terribleness of this crime changed our collective view of the woods and our profession,” one ranger told me. “It took a place we all loved and filled it with horror. I don’t think any of us will ever really get over it.”

I was listening, but I was also distracted by the racing of my heart as we got closer to the spot where Lollie and Julie had set up camp. I’ve always been agnostic about notions of the afterlife or the presence of ghosts and spirits, but I do believe that violence leaves some kind of metaphysical trace. The AT thru-hikers who stopped long enough to write in the log at the Thelma Marks Shelter (where a young couple had been murdered in 1990) noted that phenomenon again and again. Maybe it was just the power of suggestion. Maybe they saw what other hikers had written before them, and those words became their own new reality. Or maybe they’d read about the place before setting out on their hikes and were anticipating a sinister feeling. I don’t know.

The only noise is the brook, running fast and strong with snowmelt.

But here’s what I do know: As apprehensive as I was, as predisposed as I was to find something terrible and sad and stained about the place where Julie and Lollie died, I felt none of that. To the contrary, their little stealth campsite was undeniably beautiful. Even in the austerity of early March, when the canopy is bare and the forest floor is packed with dank and decomposing leaves, it is a lovely, peaceful place. The former tent site itself is the only level patch of ground in the area. It is surrounded by a horseshoe of trees that makes the place feel like a secret oasis. The only noise is the brook, running fast and strong with snowmelt. Had I been backpacking here, I would have selected this site for myself and thought I’d hit the lottery.

When Julie and Lollie arrived here in May 1996, the ground would have been soft with early ferns and new grass. The spot was the perfect size, with room for their tent and gear, and a place to sit and eat or write or just think the day away. The northern fork of the Whiteoak flows right alongside, so water for cooking and drinking was in easy reach. Best of all, because it was a backcountry spot, there was no sign announcing the place, no fire ring or picnic table. Just a delicious patch of ground tucked in the woods, with the comforting gurgle of a river’s headwaters nearby.

Today, no cross or drying wreath marks this site as the place where Julie and Lollie were murdered. The only memorial is a small scatter of brightly colored rocks that once formed a peace symbol on the ground not far from where Julie’s body had been found, a tribute left by her friends to commemorate her love of geology. Standing there studying those stones from around the world and the scene that contained them, I struggled with the cognitive dissonance of admiring a place where something so unspeakably awful had occurred. I did not know Julie or Lollie. I cannot speak for them, nor do I want to seem so presumptuous as to say what they may have felt or thought. But maybe, just maybe, when two selfless, joyful, beautiful humans die in a place, what is left behind is not the agony of their deaths but the brilliance of their lives.

From “TRAILED: One Woman’s Quest to Solve the Shenandoah Murders” by Kathryn Miles. © 2022 by Kathryn Miles. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. All rights reserved.

Catching Up With the Author

The author, Kathryn Miles.

©AMY WILTONKathryn Miles, who admits to going to “almost ludicrous” lengths to solve this case, remains closely involved in the quest for justice for Julie, Lollie, their loved ones and everyone whose sense of safety in the outdoors was threatened by the women’s murder. In a conversation with Associate Editor Katherine DeGroff this spring, Miles, now 48, spoke about the effect the women’s deaths had on her life and the lives of others, explained why investigators haven’t been able to close the case, and reflected on her attempts to reclaim her own sense of peace in the wilderness.

Why were you compelled to get involved in Julie and Lollie’s case? I am a contemporary of Lollie and Julie’s in terms of age. I’m also a sexual assault survivor, as they were. Backpacking was really how I made sense of past trauma and how I sort of found my place in the world. And I had always felt so secure, like I was the safest person on the planet whenever I was in my tent somewhere in the backcountry. So hearing that these two women, who were both very skilled outdoors leaders, had been murdered doing this exact same thing, and doing it in such a safe way, really rattled, and ultimately shattered, my sense of wilderness and who I was there. The more research I started to do, the more I realized that they weren’t alone. That there were these other cases of people who had been attacked in parks off of some of our biggest and most well-known national scenic trails. That really just got me thinking about who we all are in the wilderness and who we are in the backcountry. By total coincidence, my first teaching job happened to be at the school Lollie was attending when she was murdered [Unity College in Maine]. I was there in 2002 when the federal government very publicly announced not just an indictment in that case, but that that case would be treated as the first federal hate crime in the nation. For a very small campus community that was already really affected by September 11, seeing the impact on that community was really meaningful for me.

So many basic facts about the case remain mostly unsolved or unsubstantiated. Did that bother you? I don’t think that they’re necessarily unsubstantiated. I think that it’s what the FBI is choosing to do with the information, or not do, as the case may be. One of the things that’s unique about this case is that it became the joint purview of both the National Park Service and the FBI because it occurred in a national park. I think that both organizations learned the hard way about how difficult that is. The law enforcement rangers at Shenandoah, who know that park like the back of their hands and love it as their own place, worked tirelessly on this case, and I definitely want to make sure they get credit for that. There was a real divide though, I think. There was a cultural divide, and there was a procedural divide between how those rangers did their work, how the FBI did their work, and who was in charge. The FBI didn’t have experience investigating backcountry and wilderness crimes. This was the first case for the Richmond FBI office’s evidence response team. I think the case got away from them really quickly. But as I point out in the book, I also think it’s eminently solvable based on the evidence that still remains.

NPCA at Work

Has there been any movement on this case since you wrapped up your book? Not to my knowledge. If you talk to the investigators most intimately involved with the case, they will tell you that they solved it. That when the federal government indicted Darrell David Rice, they had the right person and that it was an inconvenience of the law that they weren’t able to pursue a conviction in that case. That is not my position. I don’t think Darrell David Rice did it. But because they feel so strongly about that and ultimately have been funneling all of the evidence and their interpretation of the evidence through that theory of the crime, they’ve done that to the total exclusion of other suspects at this point.

Would you say this is a case of confirmation bias? Yeah, and I don’t think we as American citizens realize how common that is. When you take into account that there’s something like 250,000 cold murder cases in this country, and when you couple that with the number of exonerations that have happened in just the last 20 years (something like 2,000 people have been exonerated because they were wrongly convicted of murder), you start to see how big of a problem this really is. Investigators are human. Most of them are great at their jobs, and they work really hard on behalf of all of us. And it’s terrible, grueling, emotionally exhausting work. But they’re still humans, and they come with the same biases and stereotypes and everything that we do. And I think too often that leads them to not consider evidence or not consider alternative explanations for crimes, and I think we all suffer as a result.

You think you’ve identified Julie and Lollie’s murderer. What happens next? Every single investigator that I’ve talked to has stressed to me again and again that this is a solvable case. DNA still exists. This can be solved. What it requires is the FBI’s willingness to do it. The FBI’s willingness to stand up and say, “Maybe, we made a mistake here.” I know there are a lot of cases; they’re understaffed. But it’s really pretty easy to prove or disprove whether I’m right here. And it would just create so much closure for the friends and family who remain for Lollie and Julie, as well as all the people who were so rattled by this crime.

The suspect you name is deceased, correct? That’s right. He’s a known serial killer, and he had abducted an incredibly strong and resourceful young woman who managed to escape. She got herself to a police station and was able to tell the police enough about him that they were able to track him down. A high-speed chase ensued. When he was faced with his imminent arrest, he shot and killed himself in his vehicle.

In your ideal world, what would be the best thing to come out of all your work on this? I’ve been shocked by how many people, especially people who are women or who identify as LGBTQ or nonbinary or any other social minority status, have told me just how impacted they were by this particular crime and how radically it changed their own relationship with the natural world. I know people who used to solo camp and now don’t feel safe doing so, or who are always looking over their shoulder in the wilderness, wondering if they’re safe. Knowing that this crime has been solved and the right person has been identified, whether that person is alive or dead, would really matter to a lot of people.

It seems like you went on your own journey during the research for this book, from questioning your own safety as a woman in the backcountry to being able to sleep once again through the night. Can you talk about that? I’m kind of a scaredy cat. I don’t watch horror movies. If it’s dark out, I don’t want to see anything that is scary or violent. In that regard, I think I was probably not the ideal candidate to embark on a five-year research project that was just so grim and grisly. One of the things I talk about in the book is our cultural fascination with true crime. I think part of me really understands that and really can identify with that. But I think it’s also really important to recognize that the true crime that gets presented to us — on TV and in movies and in podcasts — is ultimately a really sanitized true crime. And the work that these investigators do, the work that people like attorneys in the Innocence Project do, is just unimaginably dark at times. You know? There’s a real emotional toll that comes with that. I love nothing more than to be in the woods, but I also kind of carry this case with me. I’m trying to find ways to hold both things: that it can be true that this terrible thing happened and also that the woods are a beautiful and safe place to be.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›How would you describe your level of investment in this case? It’s funny because in the reviews people keep using the word “obsessive” to describe what I was doing. And part of me kind of pushes back on that. I also feel there’s kind of a gendered thing that’s happening. When women writers do this, we’re called obsessive, and I’ve yet to see a male journalist be called obsessive. But it is definitely true that things become almost ludicrous in my attempt to solve this. I did get really involved in the idea that this is a case that can be solved.

Knowing what you know now, would you have approached this case any differently from the outset? The thing I really realized about myself is that I’m not immune from confirmation bias. When I heard that Darrell David Rice had been indicted, I assumed that the federal government had the right guy. It took me a long time to question whether or not they had the right person. And it took me a long time to seek out the Virginia Innocence Project because I assumed they were trying to protect a guilty man.

Anything else you want to be sure to relay? One of the things that I was really surprised by is how underfunded our national parks are. I think that they’re absolutely doing their best with what they have, but there’s a massive deferred maintenance backlog, in the billions of dollars now, and there’s staffing shortages and things like that. If as a country, we really do value national parks like we say that we do, I think that we really have to start funding them appropriately so that they can be safe places and welcoming places for every American.

Editor’s Note:

In the Fall 2024 issue, National Parks ran a brief update on this story, detailing how the FBI announced in June of 2024 that a positive DNA match had led the bureau to identify the man responsible for the women’s deaths: Walter Leo Jackson Sr., who died in prison in 2018. Still, in Miles’ view, the case is not quite closed. “We don’t know how strong of a case they have against Jackson. We don’t know if Jackson acted alone,” she said. “There’s so many questions, and the FBI has refused to answer them.” Miles continues to agitate for accountability and transparency from both the FBI and the Park Service. Above all, she said, “What I don’t want to get lost at any point is just the beauty of Lollie and Julie’s lives.”