Summer 2025

New Bloom

A plant hunter strolled through Death Valley National Park on his day off. Then he found a flower he didn’t recognize.

Even amid the barren, sunbaked moonscape of the Cottonwood Mountains of Death Valley National Park, the shrub didn’t exactly scream out for attention. It was shin-high, parched and scruffy looking.

When Matt Berger, a 35-year-old botanist who loves plants so much he botanizes whether he’s working or not, first walked by it on a hike in February 2022, he identified it as a familiar native plant in the aster family. He snapped a photograph and continued on.

A year later, on another day off, he found himself driving back to the park to poke around for rare flora. He left his car on the side of a gravel road and walked back into the foothills of the Cottonwood Mountains, at the north end of the Panamint Range, scarcely a mile from where he had been the year before. It was rough going, first up an angled apron of rocks the size of bowling balls and then across razor-sharp limestone that cut his hands and pants.

Good things come to those who suffer. Two hours into his hike, he came upon a stout, spiny shrub with a single purple flower growing out of a crack in the yellowish bedrock. Berger looked closer. It was definitely an aster, and apparently the same species he had photographed before. But that plant was supposed to have yellow flowers. Here was one with a beautiful crown of violet rays. Berger’s knowledge of the park’s plants is encyclopedic, but this one was stumping him.

Botanist Matt Berger picked up the trail name Sheriff Woody while thru-hiking the Appalachian Trail.

COURTESY OF MATT BERGER“I’m pretty excitable when it comes to seeing a cool plant in general,” Berger admitted. “I’ll shout and yell. But this one, I was out there by myself. I was just kind of flabbergasted. I just looked at it with my mouth open. What? What is that?”

What it turned out to be was the single-most thrilling thing he had found in a lifetime of botany.

Berger lives in Ohio but spends much of the year in California as a contract botanist identifying weeds and rare plants for the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. Growing up, Berger was first enamored with insects. When he noticed interesting bugs gravitating toward native plants, he started collecting those seeds and sprouting them. Eventually, he grew more intrigued by the plants than the insects. He went on to get an undergraduate degree in horticulture and a master’s in plant pathology.

After college, Berger found another passion in thru-hiking. He and a friend first tackled the Appalachian Trail in 2012, when Berger, who is lanky and tall, took on the trail name Sheriff Woody. (His stout friend became Buzz Lightyear. Buzz quickly learned to keep walking whenever his companion stopped to gawk at a sedge or some curious moss.) In 2014, he first hiked the Pacific Crest Trail, which introduced him to the California deserts.

Death Valley itself is one of the hottest and driest spots on Earth, but the park also encompasses a wide range of habitats, from tall mountains riddled with springs to pinyon and juniper woodlands, and it’s a wondrous place to a botanist like Berger. “It’s just so remote and rugged and beautiful,” he said. “There’s a ton of plant diversity, really a ton of endemic plants.”

Berger was pretty sure the purple-flowered plant that stopped him in his tracks was one of those endemics, but which one? Normally, when confronting a botanical novelty, Berger would consult an inventory of California flowers and plant identification apps on his phone. He didn’t find the plant in the one resource he had with him, and since he had no service, he took some photos, pocketed his phone and trekked back to his car.

I was just kind of flabbergasted. I just looked at it with my mouth open. What? What is that?

As soon as he found service, he searched every relevant field guide and website but found no match in California or any neighboring state. Bewildered, Berger decided to fire off an email and some photos to Bruce Baldwin, an aster expert and the curator emeritus of the Jepson Herbarium at the University of California, Berkeley. Baldwin opened the pictures and gaped.

“From a distance, it doesn’t look like much,” Baldwin told me later. “But seeing those close-ups and especially those purple rays radiating around the periphery of the flowering heads was a shock.”

Want a closer look at the aster in Death Valley? Watch the video, narrated by Matt Berger. MATT BERGER

Baldwin replied, telling Berger it might indeed be a new species. To be able to formally describe it, they would need a specimen. Because the flower was in a national park, Berger would need a permit. He applied and received it about six months later. He thought he might have to wait until the following spring to collect the plant in flower, but then, in August, Tropical Storm Hilary slammed into California and dumped a year’s worth of rain on Death Valley in a day. Berger wondered if the deluge might make the aster bloom out of season.

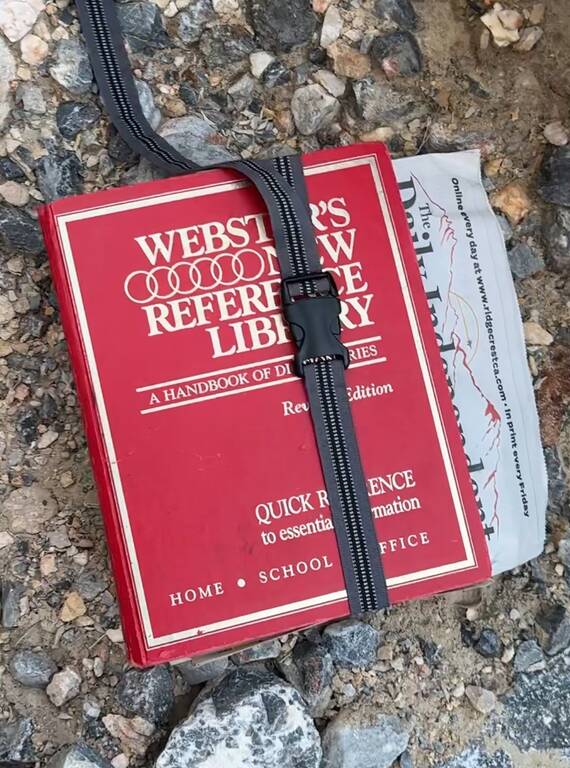

Berger picked up a dictionary at a local thrift store to create a plant press, which he used to secure cuttings of the aster.

COURTESY OF MATT BERGERThat December, Berger flew to California for a job surveying transects of the Mojave Desert. He finished his work a day early and drove back to Death Valley. He couldn’t bring a plant press, so he MacGyvered one. At a local thrift store, he bought the heaviest book he could find — a Webster’s dictionary — and a couple of belts. He packed these supplies into a backpack and walked back to the plant, which was in full bloom.

“It had mature seeds, it had flower buds on it and good fresh leaves,” Berger said. “It had every piece you need to identify and describe a plant.”

Berger carefully collected his cuttings, which he pressed between pages of the dictionary. Then he cinched the book tight with the belts. He carried the dictionary back to Ohio and mailed the specimens to Baldwin.

At his lab, Baldwin confirmed with DNA sequencing that the plant was a new species, which the pair named after the Panamint Mountains, where it grows. Last December, Baldwin and Berger published a paper introducing the world to Xylorhiza panamintensis, or the Panamint desert-aster.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Berger said that although the flower is new to science, other people had photographed and puzzled over it before. And the plant was surely known by Native Americans in the area.

For now, Berger said, it’s fortunate that the Panamint desert-aster grows in remote areas and is protected within the park. But it may already be at risk from climate change, and it could be further threatened if the area is ever reopened to mining. In April, the Trump administration promoted the mining of rare earth minerals inside nearby Mojave National Preserve.

“I think every living thing has a right to exist,” Berger said. “I know there are people who could care less. But knowing about the plant, knowing where it grows, is important if there’s going to be any plan to conserve it.”