Summer 2025

A Mass Revival?

A biotechnology company said it brought back dire wolves. Should these former park denizens be next on the de-extinction list?

Colossal Biosciences, a Dallas-based genetic engineering company, made headlines around the world this spring when it announced that it had revived the dire wolf, a larger and toothier cousin of the gray wolf that was wiped out about 10,000 years ago. Colossal said it extracted DNA from dire wolf fossils and used dogs as surrogate mothers. Most experts saw the claim as little more than fantasy, with one calling it “colossal baloney.” To be clear, NPCA is focused on preserving the parks’ current species and is not endorsing the revival of extinct animals, but nonetheless, the announcement led us to do some fantasizing of our own. Dire wolves used to roam the lands that make up today’s national parks, so what other vanished creatures could be brought back from beyond the brink?

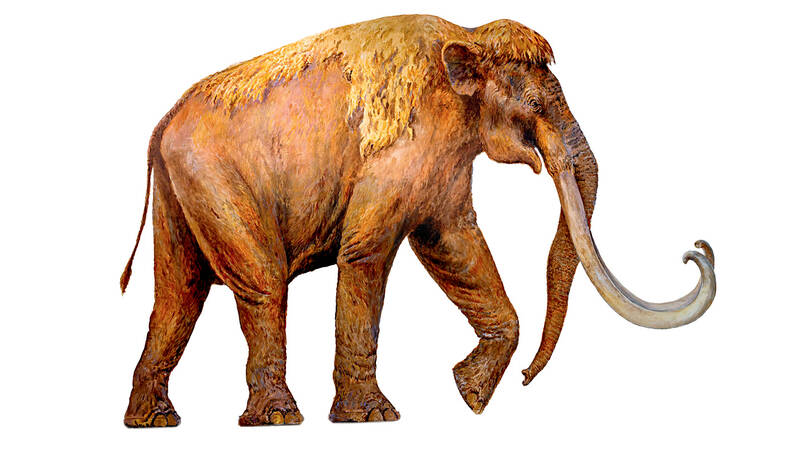

Columbian Mammoth, Waco Mammoth National Monument

This is an obvious next step since Colossal is already working on reviving woolly mammoths. Waco’s variety, the Columbian mammoth, is less hairy, which might actually be a good thing since temperatures have risen quite a bit from the most recent ice age.

Pterosaur, Denali National Park and Preserve

Parks have worked hard to restore North America’s biggest bird, the California condor, so why not revive a truly gigantic flying creature? Denali’s largest pterosaurs weighed about as much as a microwave oven, but their wingspan was equivalent to the height of a two-story house. Denali visitors need not worry: Though pterosaurs would make for an unnerving sight, the winged lizards preferred to dine on fish.

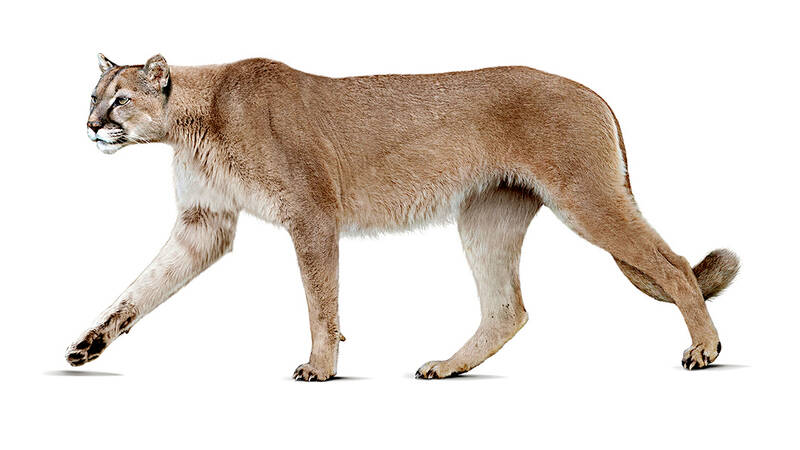

American Cheetah, Grand Canyon National Park

Pronghorns are America’s fastest land animals, and one theory is that they got so fast because they had to outrun the American cheetah, which is known to have denned in Grand Canyon. The antelope eventually left the speedy predators in the dust, as the cheetahs didn’t make it out of the last ice age, but have pronghorns gotten a little lazy in the intervening millennia? Restoring the American cheetah would light a new fire under them.

Carolina Parakeet, Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Colonists and others brought a bunch of drab invasive birds to America, such as the European starling and the house sparrow. On top of that, they managed to get rid of the green, yellow and orange Carolina parakeet, one of the continent’s most stunning avian residents and a onetime denizen of Great Smoky Mountains. Why not bring back a dash of color to our forests?

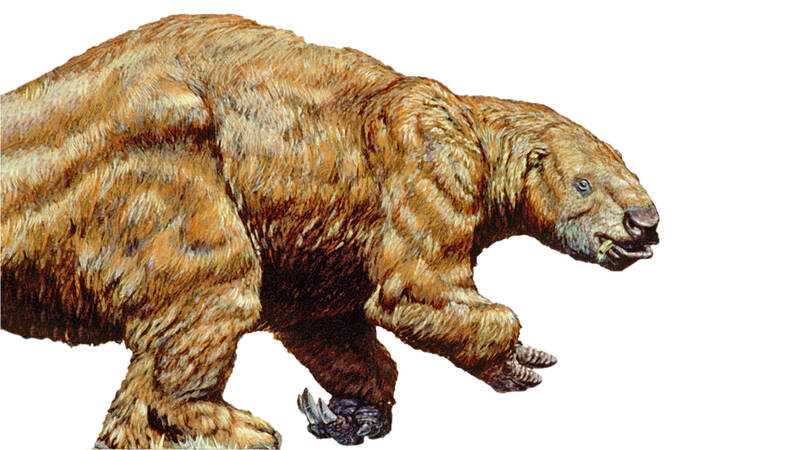

Ground Sloth, White Sands National Park

White Sands warns visitors that its animals are hard to see because they tend to be nocturnal and/or tiny, such as the Apache pocket mouse. But Harlan’s ground sloth, the area’s erstwhile behemoth, was as tall as an elephant, so it would be hard to miss. Also, sloths are in these days, so adding this big furball to the park’s roster might boost visitation numbers and plush toy sales.

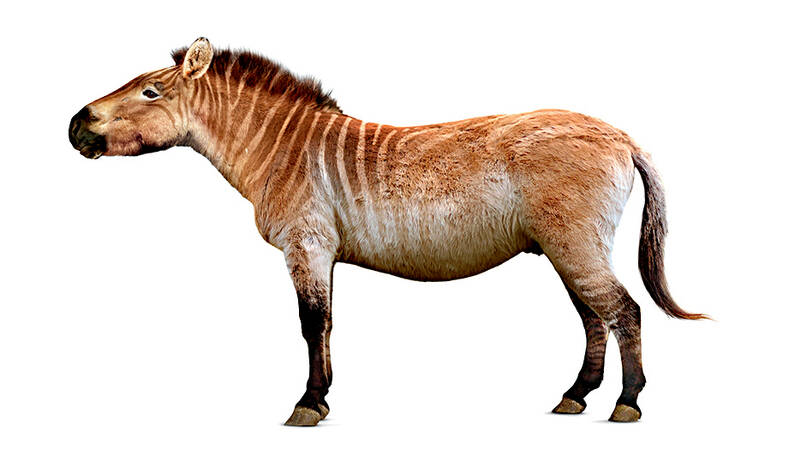

Hagerman Horse, Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument

America has had a long love affair with the horse — brought here by the Spaniards a few centuries ago. Imagine the depth of affection the horsey folks would feel for a truly native equine. So let’s not horse around, and let’s restore the Hagerman!

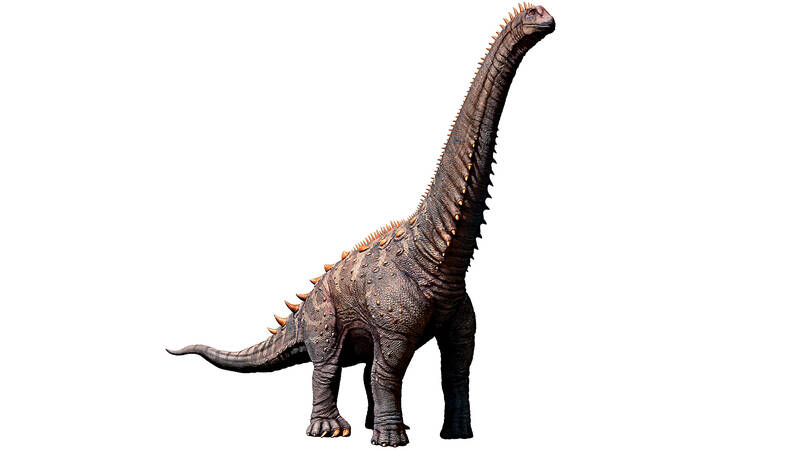

Alamosaurus, Big Bend National Park

Remember the Alamosaurus! They say everything is bigger in Texas, and that certainly is true when it comes to dinosaurs. The Alamosaurus might have been the largest creature to ever walk North America’s lands, and a specimen discovered in Big Bend was 100 feet long. Added bonus: The revived dino would make for a size-appropriate state reptile for the largest state in the Lower 48.

About the author

-

Nicolas Brulliard Senior Editor

Nicolas Brulliard Senior EditorNicolas is a journalist and former geologist who joined NPCA in November 2015. He serves as senior editor of National Parks magazine.