These women became part of public lands history as they demonstrated the principles of equality and justice celebrated each May during Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

This spring, I strolled through San Francisco’s famed Presidio for the first time. I was surprised to find, amid the noise of the city’s rush hour, a pocket of quiet. Though I had heard how special this place is (after all, it’s one of America’s most visited national park sites), I had no idea that it was graced by an Asian American leader, whose story you will learn below.

My favorite part of Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month — besides the food — is learning the stories of dedicated, resilient people who shaped parks as we know them. These are the types of conversations the Asian American and Pacific Islander Affinity Group has here at the National Parks Conservation Association.

From Hawai‘i’s National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific to New York’s Statue of Liberty National Monument, the lives of the women below brushed against public lands — including lands that would later become part of the National Park System — as they demonstrated the principles of equality and justice we celebrate each May.

It seems more apt than ever to lift up their acts of courage, as national parks have never faced more dire threats, from record-breaking staffing cuts to their greatest existential challenge yet: climate change. Looking at those who made history before us might nudge us to see our parks as sources of solace, yes, but perhaps most importantly, as the keepers of stories we must protect in perpetuity.

Dr. Margaret “Mom” Chung (1889-1959)

For more than 200 years, the Presidio of San Francisco served as an army post for three nations. In the years before and during World War II, the first Chinese American woman to become a physician played an important role among the base’s pilots — becoming an adoptive “mom” to thousands of American servicemen.

Margaret “Mom” Chung, an adoptive mother to thousands of American servicemen.

National Museum of the Navy via Wikimedia CommonsMargaret Chung frequently hosted weekly dinners for soldiers, their guests and top military personnel at her home, as many as 175 one Thanksgiving. She later secretly recruited pilots for a unit that became famous as the “Flying Tigers” — squadrons of pilots from the U.S. Marines, Air Corps and Navy who flew under Chinese colors to oppose Japan’s invasion of China. She also advocated for greater inclusion of women in the military and lobbied for creation of the U.S. Naval Women’s Reserve.

Born in Santa Barbara, California, to Chinese immigrants, Chung attended college and medical school at the University of Southern California, often wearing masculine clothing and referring to herself as “Mike.” Denied the opportunity to work as a medical missionary because of her race, she worked as a surgical nurse and later medical resident in the Chicago area before moving to Los Angeles in 1919 to start a private practice for rising Hollywood stars.

When Chung founded one of the first Western medical clinics in San Francisco’s Chinatown in the 1920s, many Chinatown residents treated her as an outsider. She was a single woman doctor, dressed in men’s clothing, who practiced western medicine and also was rumored to be a lesbian. As a result, she became more successful in attracting non-Chinese patients and building connections beyond Chinatown.

Yuri Kochiyama (1921-2014)

For 50 years, Yuri Kochiyama spoke out about injustice and oppression in the United States as a political and human rights activist. She advocated for the liberation and empowerment of African Americans, Asian Americans and Puerto Ricans. She even participated in a takeover of the Statue of Liberty in 1977 in support of Puerto Ricans, during which their country’s flag was hung from the statue’s crown.

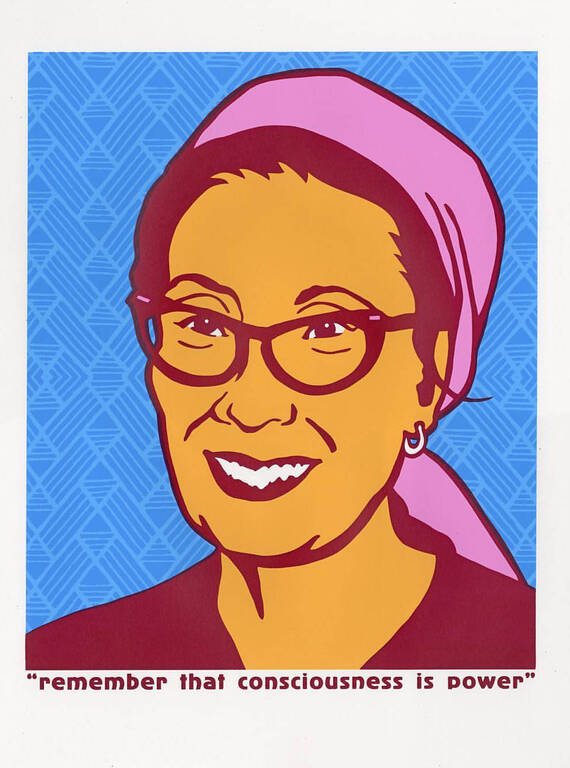

An artist’s rendering of Yuri Kochiyama, political and human rights activist.

dignidadrebelde via Wikimedia CommonsThe child of first-generation Japanese Americans, Mary Yuriko Nakahara was raised in San Pedro, California. After the bombing at Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the U.S. government forcibly evacuated her family along with 120,000 other Japanese American citizens under President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, issued in February 1942. They lost their family business and personal assets and spent most of the war at the Jerome Relocation Center in Arkansas.

She got out of the incarceration site in 1944 by volunteering to work at an all-Japanese, segregated United Service Organizations Center in Mississippi, where she met her husband, Bill Kochiyama.

After the war, the Kochiyamas raised six children in Harlem, where Yuri displayed her lifelong commitment to social justice as an organizer, coalition builder, writer and speaker. Among her causes, she advocated for reparations for Japanese American incarcerated during World War II and the release of prisoners whom she regarded as prisoners of conscience. A student of Malcolm X, she described herself as a “revolutionary international anti-imperialist.”

Cecilia Cruz Bamba (1934-1986)

Americans have a greater understanding of the effects of the War in the Pacific on the people of Guam thanks to Cecilia Cruz Bamba, who became the first Indigenous woman from that island to testify before Congress about wartime atrocities.

Cecilia Cruz Bamba, war reparations advocate.

The Bamba FamilyAs a child, she lost both her mother and father in the 1940s during the Japanese attacks on Guam. She was raised by her grandmother, and at age 16, married 20-year-old George Mariano Bamba, who became a businessman and politician. Together they raised 10 children. Cecilia, too, became a businesswoman, community leader and senator in Guam’s legislature.

As a war reparations advocate, she was a champion for the Chamorro people who suffered, died or lost their lands because of the war effort — frequently traveling to the continental U.S. to organize meetings to meet hundreds of survivors and document their stories. She introduced legislation for the establishment of the War Reparations Commission, and in 1983 testified before Congress. After her death, her son George Bamba Jr. continued her advocacy for reparations and told her story during another congressional hearing in 1988. Reports from those proceedings became known as the “Bamba Files.”

War In the Pacific National Historical Park in Guam was established to commemorate the sacrifice of those participating in World War II’s Pacific campaigns and to conserve and interpret the island’s natural and cultural resources.

Tye Leung Schulze (1887-1972)

The U.S. Immigration Station on San Francisco Bay’s Angel Island is a National Historic Landmark for its long military history and role as the “Ellis Island of the West” in the early 1900s. After taking a civil service exam in 1910, Tye Leung Schulze became the federal government’s first Chinese woman employee when she was hired to work in Angel Island’s women’s quarters and translate for detained Chinese immigrants.

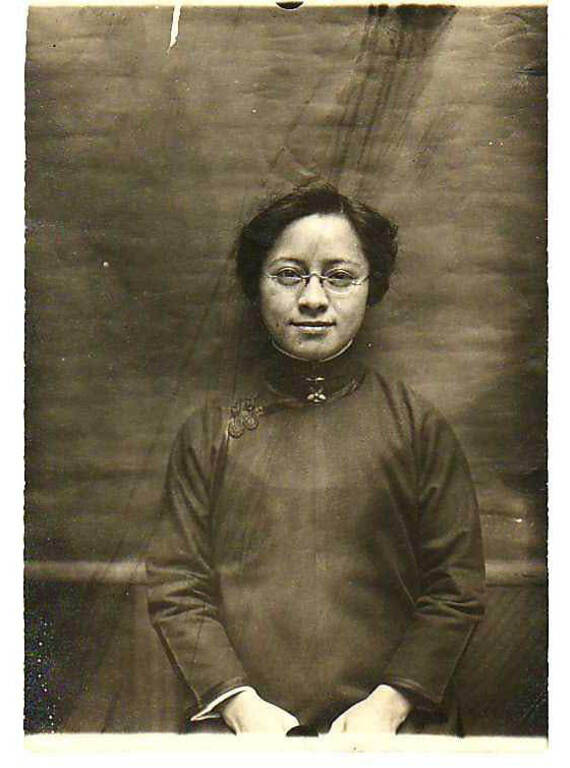

Tye Leung Schulze, civil rights and community activist, in 1912.

Unknown photographer via Wikimedia CommonsTwo years later, she became the first Chinese woman to cast a vote in the United States, and possibly the world, when she voted in the presidential primary in California.

She met her husband, immigration inspector Charles Schulze, while working at Angel Island. Because of laws banning marriage between whites and Asians, the couple had to travel to Washington State to get married — and when they returned, lost their jobs because of their interracial marriage.

They settled in San Francisco and held various jobs, with Tye providing translation services for the Chinese community and working as a community advocate.

Born in San Francisco’s Chinatown, Tye learned how to be a translator and interpreter at the Presbyterian Mission, which she escaped to as a young teen resisting an arranged marriage. Considered a star pupil at her new home, she assisted her teacher in court as part of the mission’s work to free Chinese women from sex slavery.

U.S. Rep. Patsy Mink (1927-2002)

National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, created in 1948 to accommodate soldiers who died in World War II, is on the National Register of Historic Places in Honolulu. Among those buried there is the first woman of color and first Asian American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, as well as the first Asian American women to run for U.S. president.

Patsy Matsu Takemoto was born on the island of Maui, the child of second-generation Japanese immigrants. After medical schools rejected her applications because of her gender, she applied to University of Chicago Law School and got accepted mistakenly as part of a “foreign student quota” despite being born in the then-U.S. territory of Hawaii. She met her husband, John Mink, at the university.

Stay On Top of News

Our email newsletter shares the latest on parks.

Because of her race and interracial marriage, law firms in Chicago would not hire Mink — nor would firms back home when she and her husband moved to Hawaii, despite her becoming the territory’s first woman licensed as an attorney. Instead, she started a private practice in 1953 and two years later became an attorney for the Hawaii territorial legislature. She was later elected to the territorial House and Senate.

After Congress admitted Hawaii as a state in 1959, she ran for the single seat in the U.S. House of Representatives but was defeated. Undeterred, she ran again when the state obtained a second seat based on the 1960 census and won. She served in the House from 1965 until 1977 and became a fierce advocate for women, children and minorities. She ran for president in 1971 as an anti-Vietnam War candidate. She was a major author and sponsor of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in educational institutions that receive federal funding.

NPCA’s Linda Coutant contributed to this report.

About the author

-

Lam Ho Former Senior Climate Communications Manager

Lam Ho Former Senior Climate Communications ManagerDuring her time as NPCA’s Senior Climate Communications Manager, Lam called attention to the effects of climate change on public lands with an emphasis on air quality and environmental justice.

-

General

-

Issues