Spring 2021

Lest We Forget

One man’s 30-year mission to honor the lives of more than 260 Park Service employees and volunteers who died while working in the parks.

Jeff Ohlfs likes to joke that a night out, in his household, is dinner in a graveyard.

Over the years, the former Joshua Tree National Park chief park ranger has picked up the habit of visiting the cemeteries where fallen Park Service personnel are buried. He might tack on a visit to Arlington National Cemetery while in Washington, D.C., for business or modify the itinerary of a family vacation to accommodate a graveside rendezvous. The routine is always the same. “I will stop in, pay my respects and grab a photo,” Ohlfs said. So far, he’s made it to nearly 60 graves.

Ohlfs’ solemn pursuit is part of a pet project decades in the making: an online memorial dedicated to the employees and volunteers who have died while working in the national parks. “We need to honor these individuals,” Ohlfs said, noting how everyone has his or her own story. “As Park Service people,” he continued, “part of our job is to tell the story.”

In 2016, after a 32-year Park Service career that started at what was then Pinnacles National Monument and ended at Joshua Tree, Ohlfs retired to nearby Twentynine Palms, California, where he lives with his wife and their dog. With more time on his hands, Ohlfs — a self-proclaimed closet historian — kicked his memorial work into overdrive in the last few years, racing to make it public. His motivation was simple: “I wanted to make sure these people aren’t forgotten,” he said.

Last year, in time for the 104th anniversary of the Park Service, Ohlfs’ employee memorial went live, to his great relief. “It has a home,” he said. The memorial is hosted on the private domain NPShistory.com — a treasure trove of publications, brochures and reports that is the brainchild of Harry A. Butowsky, a retired Park Service historian, and Randall D. Payne, a Park Service volunteer.

“I was urging him just to get it done and put it up,” Butowsky said, recalling Ohlfs’ reluctance to launch the website before he had every last detail. “I said, ‘Look, if we’re missing names, don’t worry about it. We can add the names.’ … But Jeff was very thorough. He didn’t want to miss anyone.”

The memorial, which spans more than a century, sparingly documents the lives of 264 men and women, and includes references to more than 90 parks in over 35 states and territories. Andrew Jack Gaylor, assistant chief ranger for Yosemite National Park, for example, is listed as having died in 1921 of a “heart attack on high mountain patrol while sitting before his campfire … died with his boots on.” A 2004 entry states that Suzanne Roberts, a ranger at Haleakalā National Park, died after being “hit in the upper back and head by a boulder in excess of three feet that fell from [a] cliff” as she was clearing a rockslide from a road.

Each life has been distilled into a handful of data points — job title, age, cause of death, years of service, final resting place. Most entries also include a photo of the person in uniform or on the job. Sometimes, all Ohlfs had was an image of a gravestone, obtained online or taken during one of his cemetery side trips. “I wanted to show: ‘This is where they are. This is their resting place,’” Ohlfs said.

The roots of this endeavor date back to 1988 when Ohlfs, then a ranger at Hot Springs National Park in central Arkansas, stumbled across a reference to the 1927 murder of James Alexander Cary, a park policeman. The case wasn’t well known, and the story wasn’t being told by the park, so Ohlfs took it upon himself to honor Cary by learning about the man’s life and death, befriending the policeman’s family in the process. He also pushed for the park to memorialize Cary but said he received no support. (A memorial was finally erected in 2016.) In the course of Ohlfs’ informal research into Cary, it became clear there were many others who died while working in the parks but whose stories were largely unknown and untold.

“We honor our military fallen,” Ohlfs said. “We honor our emergency services people. The National Park System isn’t too far away from that.” In fact, serving as a national park ranger, according to FBI data, is one of the most dangerous federal law enforcement details, with assaults against rangers outnumbering those against officers of the FBI, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, and the Drug Enforcement Administration, for example.

While Ohlfs supports the memorials specific to police officers or firefighters (such as the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial in Washington, D.C.), he envisioned a more inclusive listing that honored everyone, no matter how long they worked for the Park Service, what position they held or how they died. In doing so, he said he hoped more people would “recognize that maintenance personnel and secretaries and superintendents and interpreters have all paid a price for the National Park Service.”

In January of 1993, Ohlfs read an article in the Park Service’s magazine, Courier, that revealed the installation of a plaque outside of the Park Service director’s office in Washington, D.C., to honor those who perished while on the job. The Courier reproduced the plaque’s list of names and asked all employees and alumni to supply information on those overlooked. Ohlfs heeded the call and began searching for more names, forwarding updates to a contact he had in the Washington D.C. Area Support Office.

Soon, his off-the-clock efforts took on a life of their own. He perused microfilm of back issues of the Courier and other Park Service publications for leads or references to park deaths. He read book after book about the parks, noting any mention of on-duty fatalities. He sent out inquiries to the relevant parks, followed up on possible deaths passed on to him by park staff, and scoured newspaper and museum archives, paying records fees out of his own pocket. “It’s all detective work,” Ohlfs said. “Law enforcement rangers like working a case.”

A few years later, Ohlfs discovered a pamphlet published by the California Highway Patrol honoring its slain officers. Instead of the index of names featured on many memorials, including the Park Service plaque, this publication included other details, like the ones Ohlfs was amassing. Curious if the Park Service might do something similar, he shared the idea with his contact at the agency’s Washington headquarters. There was a spark of interest, but it soon fizzled. Undaunted, Ohlfs forged ahead.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Occasionally, family members of the deceased would reach out to him, grateful to be able to share their loved one’s story. Others, their loss too private or too raw, refused to speak to him. He received a similarly mixed response from the park employees he contacted, none of whom are required to keep these kinds of details on record. “Some parks will bend over backwards to help,” Ohlfs said. “And some will tell me to go pound sand.”

The stories he has uncovered run the gamut from mundane to bizarre to mysterious. In 1959, George Sholly, the superintendent of what was then known as Badlands National Monument, suffered a heart attack while sitting at his desk. The previous year, engineering technician Charles Wallace died from tetanus as a result of a yellow jacket sting at Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks. Seasonal ranger Ryan Weltman, surprised by a sudden turn in weather, drowned in 1994 when his kayak capsized on Yellowstone National Park’s Shoshone Lake. Six women and one man, all between the ages of 20 and 45, died in a plane crash while conducting an aerial land survey at what would become Lake Clark National Park and Preserve in 1975.

Dozens more died repairing trails, operating heavy machinery, clearing snow or fighting fires. Still others perished during daring rescues to save the injured, the lost or the stranded. The history of the park system also includes the occasional sensational murder. Park staff have died at the hands of poachers, prison escapees, drunk drivers and, in one instance, an unstable dog owner.

Invariably, several of the leads Ohlfs found proved particularly difficult to verify. He might have a name or a reference to a specific year and park where someone died, but little else. Last February, he submitted more than 20 outstanding names to the National Archives and Records Administration, and the list landed on the desk of archival reference technician George Fuller.

Fuller, who fondly recalls his own brief stint with the Park Service in 2014 as a museum technician at what is now Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park, has access to the personnel records of anyone who has worked for the federal government. He loves “helping people find pieces to their own puzzles” and was eager to assist Ohlfs with his project. “I think it’s quite profound,” Fuller said. “That he has dedicated so much time and energy and effort and his own resources to make this a reality is incredible.”

Unlike physical monuments such as the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Ohlfs’ memorial does not offer the opportunity to trace a loved one’s name on paper or leave behind personal tributes. The benefit of a digital site, however, is that it is as easy to visit as it is to share. Ohlfs hopes people will come forward with additional names, photos and stories as knowledge of the memorial expands.

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR

Since it went live last August, about two dozen edits and updates have been submitted, mostly by former or current Park Service staff. Doug Crossen, supervisory facility operations specialist at Wind Cave National Park, was one of several people to offer new names. After noticing that Michael Carder, an equipment operator who died in 2017 while leading a trail crew at Jewel Cave National Monument, was missing from the memorial, Crossen contacted NPShistory.com to ensure Carder was included. “Mike loved his job, loved getting to work in the morning,” Crossen recalled.

Ohlfs estimates it will take a few more years to plug the information gaps in existing entries or corroborate the additional leads that continue to trickle in. Even then, he won’t be done. The bittersweet reality of a memorial to fallen park staff is that it will grow with the passage of time. “We hope it never happens, that the last one I put on there is the last one,” Ohlfs said. “But it’s going to be never-ending because that’s just life.”

To view the memorial, visit http://npshistory.com/employee-memorial/.

There are 264 people commemorated in Jeff Ohlfs’ online memorial so far.

Writer Katherine DeGroff investigated the lives and premature deaths of a few of them.

Nicholas (Nick) Hall

Mount Rainier National Park, 2012

On June 21, 2012, a helicopter dispatched from a military base near Tacoma flew park ranger Nick Hall and other rescuers to the scene of four injured Texas climbers on the eastern flank of Mount Rainier, the 14,410-foot behemoth in the eponymous national park. Once there, team members worked for several hours to stabilize the seriously injured and secure them in litters, which would be lifted into the helicopter and flown to a nearby hospital. Conditions were perilous: slick snow, gusting winds, powerful rotor-blade downdrafts and a 35-degree slope.

Hall, the former Marine Corps sergeant tasked with leading the rescue’s aerial response, was a skilled ski patroller who had worked as a climbing ranger at Mount Rainier for four seasons. Quietly confident, Hall possessed a dry wit and had an “intensely caring and professional” nature, according to Stefan Lofgren, the park’s climbing program supervisor.

Just before 5 p.m., Hall lost his footing while attempting to control the slide of an empty litter. Despite efforts to stop his momentum, he fell 2,400 feet to his death.

The remaining rescuers, though reeling from the loss of their colleague, successfully evacuated three of the Texans. Rangers spent the night on the mountain with the last climber, who walked out with assistance the following day.

I’d love to be able to call Nick up some day and say, ‘Hey, Nick. Thanks, man. I really appreciate you being up there and taking care of me like you did that day. I will never be able to do that.

In 2017, the park honored the lives of Hall and three others who had died in the line of duty in the previous 25 years, with the designation of the Mount Rainier National Park Valor Memorial. Perhaps no one feels the weight of Hall’s sacrifice more keenly than Lofgren, who received Hall’s lifesaving assistance during his own mountainside emergency in 2011.

In a phone conversation in December, Lofgren shared how he radioed for help after struggling to breathe and suffering a seizure near Mount Rainier’s Camp Muir. Hall responded to Lofgren’s report of an “individual down,” having no idea the person in need of aid was his boss. “I’d love to be able to call Nick up some day and say, ‘Hey, Nick. Thanks, man. I really appreciate you being up there and taking care of me like you did that day,’” Lofgren said. “I will never be able to do that.”

Mason McLeod, Neal & Seth Spradlin

Katmai National Park and Preserve, 2010

If the Alaska Peninsula is a weathered forearm reaching into the Bering Sea, Katmai is the 4-million-acre elbow. Home to low-lying tundra, turquoise lakes and craggy Aleutian peaks, this formidable landscape swallowed a seaplane and its occupants in 2010.

Katmai National Park and Preserve

National Park ServiceThe three Park Service employees on board — Mason McLeod, 26, and brothers Neal and Seth Spradlin (28 and 20, respectively) — were returning from a multiday project along the park’s eastern coastline where they had been repairing an old ranger patrol cabin with two other employees. On August 21, despite oppressive clouds and rain, pilots landed two private air taxis at their remote camp. McLeod and the Spradlin brothers boarded one plane; their two colleagues boarded the other.

Though the planes, both bound for park headquarters in King Salmon, departed mere minutes apart, only one plane arrived as expected. A multi-agency search for the aircraft piloted by Marco Alletto, 47, ended more than a month later — after 60,000 flight miles had been logged — when an aerial pass revealed pieces of wreckage along the coast. All four occupants were presumed dead.

McLeod, a National Merit Scholar from Florida with a fondness for Cormac McCarthy books, had recently earned his pilot’s license and harbored dreams of being a bush pilot in Alaska. He was a “super outgoing, high-energy kid,” said Troy Hamon, the chief natural resource manager and a boat instructor at Katmai, in a recent phone conversation. He remembered McLeod’s determination, recounting how the young employee had refused to give up after failing to master a required docking skill in Hamon’s boating class. McLeod met Hamon the following day and performed the maneuver flawlessly.

The outdoorsy Spradlin brothers had worked together at Katmai for two summers. Seth, in perpetual search of something to fix or build, was a wildlife artist saving money for college. In his early 20s, Neal had lived nomadically, working his way from the family home in Indiana across the West and finally to Alaska, where he had resided for five years. Hamon described him as remarkably capable, noting his ease in the backcountry and on water. “He was one of those people who could do anything,” he said.

Roderick (Rick) Hutchinson & Diane Dustman

Yellowstone National Park, 1997

For nearly three decades, Yellowstone National Park benefited from the enthusiasm and expertise of Roderick (Rick) Hutchinson, a park geologist. Hutchinson — who began his career in 1970 as a Norris Geyser Basin naturalist — relished sharing his passion for the park’s hydrothermal features with visitors and often delighted children by using water and his cupped hands to simulate a geyser. “He loved natural phenomena,” his widow, Jennifer Whipple, said recently, recalling how he once woke her before dawn so they could catch a glimpse of the Hale Bopp comet.

In 1997, Hutchinson and Diane Dustman, a park volunteer from Boston, embarked on a late-winter ski trip to the Heart Lake Geyser Basin as part of a park-wide hot springs inventory. Dustman, who had a geology degree and Master of Business Administration, had fallen in love with the park on a cross-country road trip years before and was eager to help digitize Hutchinson’s findings.

The two snowmobiled to the trailhead and then skied to a patrol cabin on the shore of Heart Lake. They spent the next day touring the area. On March 3, two days shy of Hutchinson’s 50th birthday, an avalanche swept down the slope on which they were skiing, burying them both.

When they failed to radio in their status (a routine part of backcountry work) or meet colleagues at the geyser basin as planned, the park began a full-out search, complete with dog teams, on-the-ground staff and helicopter support. Their bodies were found a few days later under several feet of snow.

Whipple, who was park botanist for many years, takes some consolation in the fact that Heart Lake Geyser Basin was Hutchinson’s favorite spot. “If he had to be killed somewhere,” she said, “it was the right place.”

Joseph Anthony (Tony) Dean

Grand Canyon National Park, 1980

In 1978, Joseph “Tony” Dean moved his family from Washington, D.C., to Yellowstone National Park. The former Maryland high school teacher had spent nearly a decade at the Park Service, filling multiple roles in the National Capital region, from seasonal community relations specialist to manager of Frederick Douglass’ home.

Taking the blended position of North District naturalist and park historian at Yellowstone meant a drastic change for the Dean family. They had little experience living outside of a city, and they would be the first Black family to live in the park.

“I think it took a lot of courage just to make that move to come here and assume a very visible and prominent role,” said Linda Young, then a seasonal employee supervised by Dean. She recalled the small Mammoth community wholeheartedly welcoming the “instantly likable” Dean, his wife and their two children. Now Yellowstone’s chief of the division of resource education and youth programs, Young credits Dean with securing her first permanent Park Service job.

I think it took a lot of courage just to make that move to come here and assume a very visible and prominent role.

In 1979, Dean accepted a position at the Horace M. Albright Training Center in Grand Canyon National Park. Though reluctant to uproot his family again, he believed in the center’s mission and admired the commitment of the instructors, whose energy he had witnessed firsthand in his early days with the Park Service.

On November 1, 1980, participants in a three-day field course led by Dean woke up to find him missing from their campsite on Horseshoe Mesa, a U-shaped promontory about halfway between the canyon’s South Rim and the Colorado River. After looking for him, the participants located Dean, 43, at the foot of a nearby cliff, where he had fallen to his death in what was later deemed an accident.

Young remembered being shocked by the news. Even 40 years later, she said, “it’s still one of those claps-of-thunder moments. It didn’t seem real.”

William Shaner & Ashley Smith

Fire Island National Seashore, 1966

On May 21, 1966, William Shaner — a high school science teacher with a penchant for collecting rocks — clocked in for the first day of his summer naturalist job at Fire Island National Seashore. Located on a thin spit of land south of Long Island, the park is a favorite haunt of day-tripping urbanites, who go there to enjoy the sandy footpaths, beaches and maritime forest.

Sunset at Fire Island National Seashore

National Park ServiceShaner, 23, was speaking to visitors on the beach at Sailor’s Haven mid-morning when he became aware of two teens in distress in the heavy surf. The emergency was also apparent to Ashley Smith, 37, a nearby park maintenance worker and U.S. Navy veteran.

The two men grabbed a flotation device and, shedding their shoes and outer clothes, began swimming out to assist the high school seniors. A bystander, 25-year-old barge crewmember James Lawler, retrieved a life preserver from a boat and joined the rescue. Shortly after reaching the boys and passing over the life preserver, all three men were swept farther out to sea.

James Del Giudice, a witness on shore, saw one boy make it back to land and set out to assist the teen who was still struggling. With the second teen safely on shore, Del Giudice then secured a rope, held by onlookers, to his waist before returning to the water to collect Smith, the only rescuer still visible. Smith, father of three daughters, died en route to the hospital. The bodies of Lawler and Shaner later washed to shore.

In light of their heroic efforts, all four men were awarded the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission’s Carnegie medal. Shaner and Smith were also posthumously recognized with the Department of the Interior’s valor award. In the 1970s, around the time that Smith’s daughter Kathleen worked at the national seashore, the Park Service commissioned a boat in Smith’s honor. A decade later, the park commissioned a patrol vessel for Shaner.

James Alexander Cary

Hot Springs National Park, 1923

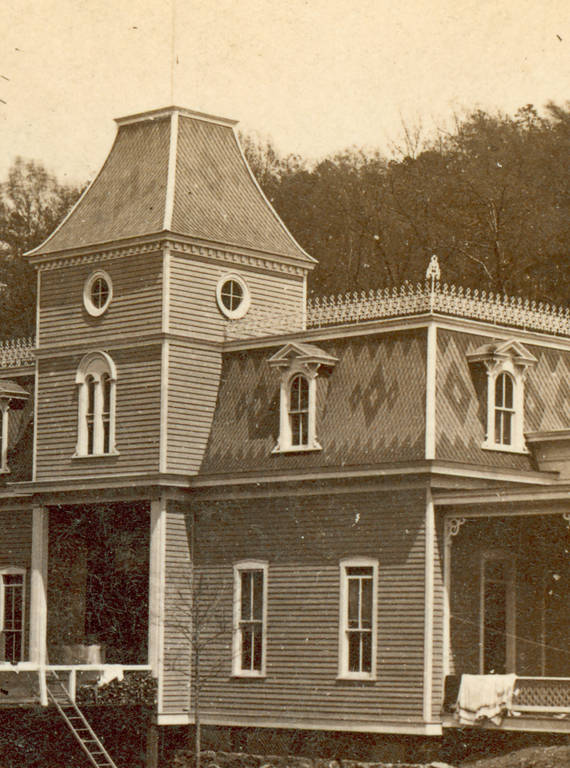

The opulent architecture of Bathhouse Row in Hot Springs reveals little of this town’s salacious past. During the late 1800s to mid-1900s, the allure of the resort town’s restorative waters was matched only by its notoriety as a major hub for gambling, bootlegging and prostitution.

Hale Bathhouse, 1916

National Park ServiceIn 1923, at the height of Prohibition, Hot Springs National Park hired James Cary as a park policeman. A World War I Navy veteran, Cary was a fierce opponent of bootlegging, especially when it involved using park lands. His diligent efforts to patrol the park resulted in the arrest of three bootleggers in December 1926. Cary was set to testify at the men’s trial in April 1927.

On March 12, while staking out an area on West Mountain, southwest of town, Cary was shot and killed. The park superintendent, noticing Cary’s absence that evening, instigated an all-night search. His body was found early the next morning.

Cary, 31, the first park ranger slain in the line of duty, left behind a wife and two small children. The FBI’s case led to the arrest of several men, none of whom were convicted of the murder. One man did serve 366 days in prison for violating prohibition laws.

In 2016, 89 years after his death, the park dedicated a memorial to Cary.

About the author

-

Katherine DeGroff Associate and Online Editor

Katherine DeGroff Associate and Online EditorKatherine is the associate editor of National Parks magazine. Before joining NPCA, Katherine monitored easements at land trusts in Virginia and New Mexico, encouraged bear-aware behavior at Grand Teton National Park, and served as a naturalist for a small environmental education organization in the heart of the Colorado Rockies.