There is more work to do to honor one of our country's most important civil rights and labor rights leaders and create a more inclusive park system for all.

Dr. Rast will be participating in a free NPCA webinar on the César E. Chávez National Monument on Thursday, October 1, 2020. Learn more about the webinar and how to join.

Using his authority under the Antiquities Act, President Barack Obama established the César E. Chávez National Monument on October 8, 2012. At the time, there were 397 units in the National Park System. A handful of those units were associated with Spanish colonization and other aspects of our nation’s Hispanic heritage, but none were associated with modern Latino history. The Chávez National Monument was the first.

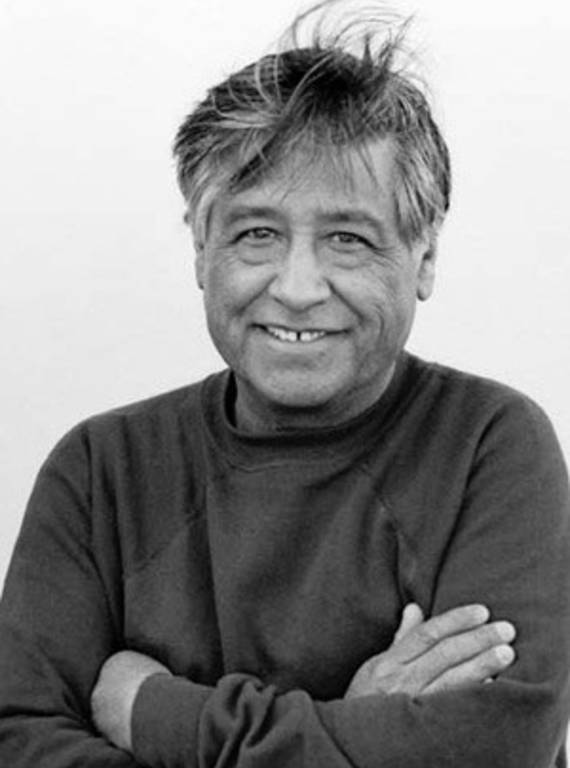

César Chávez, a leader whose non-violent advocacy led to unprecedented victories in labor and human rights.

Courtesy of the César Chávez FoundationThe election was four weeks away, and some critics claimed this was a crass effort to pull Latino voters to the polls. (Ruben Navarette, Jr. derided it as “some campaign aide’s bright idea of how to turn out Latino voters.”) Yet this was no last-minute scheme — far from it. In fact, it was the culmination of a decade-long process defined by collaboration, extensive research, public input and the carefully developed recommendations of National Park Service professionals.

If anything, establishment of the Chávez National Monument was long overdue. And it was only the first step in a march that must continue.

The 10-year process began in 2002, when the Park Service partnered with the César E. Chávez Foundation and the Historic Preservation Program at the University of Washington. Working together, the partners would identify sites and properties associated with the life of César Chávez and the history of the farmworker movement that might merit listing on the National Register of Historic Places, designation as National Historic Landmarks (NHLs), or even consideration for inclusion in the National Park System.

I was a graduate student at the University of Washington, working toward my Ph.D. in History and pursuing my interests in place-based history. The director of the Historic Preservation Program, Gail Dubrow, invited me to play a key role on this project. As the grandson of Mexican immigrants, I jumped at the opportunity.

Over the next two years, I conducted archival research and oral history interviews, identified a few dozen sites and properties, and drafted two NHL nominations. The first was for a property in Delano, California, known as Forty Acres, which served as the original home of the labor union that became the United Farm Workers (UFW). I revised this nomination in 2006, and Interior Secretary Dirk Kempthorne finally approved it two years later.

By that point, Congress had authorized a much broader study of sites and properties associated with Chávez and the farmworker movement. When the National Park Service received funding for this special resource study in 2009, I was an assistant professor at California State University, Fullerton. The cultural resources chief for the Pacific West Region, Stephanie Toothman, invited me to serve as the primary consultant for this study, and again I embraced the opportunity, knowing this time I could mentor students of my own.

Our team secured information and input from Chávez family members such as César’s brother Richard, sister Rita and son Paul; UFW co-founder Dolores Huerta; then UFW President Arturo Rodríguez; movement leaders such as Luis Valdez, LeRoy Chatfield and Deacon Sal Alvarez; and many other movement veterans and community stakeholders. By 2012, we had analyzed more than 100 sites and properties, including five that merited consideration as potential national park units.

One of the five properties was Forty Acres. Another was Nuestra Señora Reina de La Paz, a 187-acre property in the Tehachapi Mountains about 30 miles east of Bakersfield, California. La Paz became the headquarters of the UFW — and the Chávez family home — in 1972. A small portion of this property would become the Chávez National Monument.

After drafting the NHL nomination for Forty Acres in 2004, I drafted another for La Paz. I documented the history of the property from the 1920s to the 1960s, decades during which it developed as a tuberculosis sanitorium (with two dozen medical, residential and administrative buildings), and then since the early 1970s, when it evolved as the headquarters of the UFW and other affiliated organizations.

The property had gained national historical significance through its close association with Chávez, one of the most important Latino civil rights and labor rights leaders in U.S. history, and through its close association with the UFW, the first enduring agricultural labor union in U.S. history.

For scores of union staff members and their families, La Paz literally became a new home in the 1970s. For Chávez in particular, it became a refuge — a place to re-energize, strategize and envision the future of a movement that would encompass but also transcend the needs of workers in the fields. As he told writer Jacques Levy in 1975, “After we’ve got contracts, we have to build more [health] clinics and co-ops. Then there’s … so much political work to be done taking care of all the grievances that people have, such as the discrimination their kids face in school, and the whole problem of the police. … We have to participate in the governing of towns and school boards. We have to make our influence felt. … It’s a long struggle that we’re just beginning, but it can be done because the people want it.”

Chávez lived at La Paz with his wife Helen from 1972 until his death in 1993. That he wished to be buried at La Paz is an enduring testament to the strength of his association with the property.

For the UFW as a whole, La Paz became a site for managing the union’s operations, training organizers and negotiators, debating and developing strategies, celebrating victories, and regrouping after defeats. For members and supporters of the broader movement, La Paz became even more — it became a symbol of the movement’s expanding horizons, its push toward innovation, its investments in new technology, and its experimentations with communal living and community building. As one volunteer told the Los Angeles Times in 1972, a visit to La Paz was like “a journey to Mecca.” It was “so peaceful. And once you visit it you just feel … more tuned in to the whole movement.”

This NHL nomination still had not moved forward when, in 2010, the Chávez Foundation decided to nominate La Paz for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. I offered assistance, and the Chávez Foundation submitted a nomination to the California Office of Historic Preservation. It was approved and La Paz was listed in August 2011.

Exactly Where We’re Meant to Be

How a weeklong celebration of people who look like me can create a greater sense of belonging for the Latinx community in the outdoors.

See more ›A year later, the Park Service had confirmed the property’s eligibility as a National Park unit and recommended its protection. The National Chávez Center at La Paz soon agreed to donate 10 acres of land. In accepting this donation and establishing the Chávez National Monument, President Obama noted that La Paz “marks the extraordinary achievements and contributions to the history of the United States made by César Chávez and the farmworker movement.” The Chávez National Monument was established — at long last — because it is a key part of an important chapter in our nation’s history.

The National Park Service had long neglected such chapters. Recognizing as much, Interior Secretary Ken Salazar launched the Park Service’s American Latino Heritage Initiative in 2011. When the initiative began, the Park Service counted around 2,400 National Historic Landmarks. Only three had any connection to Latino history during the 20th century: Ybor City Historic District in Tampa, the Freedom Tower in Miami and Forty Acres. Among its many accomplishments, the initiative led to 11 new NHL designations for sites associated with Hispanic heritage or modern Latino history. One of them was La Paz — formally approved by Secretary Salazar on the same day that President Obama established the monument.

All of these efforts to identify, protect and interpret sites associated with modern Latino history are important because truthful representation of our nation’s diversity matters, now more than ever. America’s Latino population has surpassed 60 million — which equals the combined total of the 32 least-populous states and territories in the U.S. A map of the U.S. that did not include those 32 states and territories would be not only incomplete and inaccurate, it would perpetuate a kind of ignorance that would undermine our national unity. The same could be said for a National Park System — and any of our federal, state and local registers — that failed to faithfully represent Latino history.

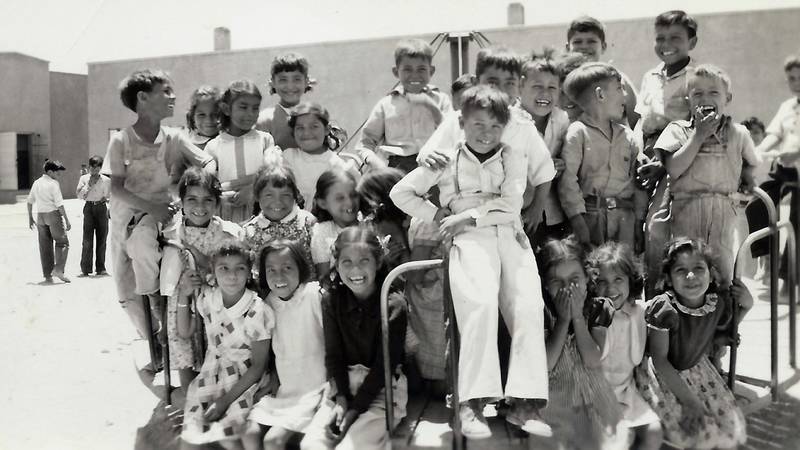

The Complicated History at One of America’s Segregated Schools

One student shares her experiences at the Blackwell School in Marfa, Texas, a site many want preserved in the National Park System.

See more ›President Obama’s establishment of the Chávez National Monument was an important first step. The work of the American Latino Heritage Initiative was another. The march has continued, and several national organizations have joined in — not only NPCA and the National Trust for Historic Preservation but newer organizations such as Latinos in Heritage Conservation and the Hispanic Access Foundation. Other agencies and organizations are doing great work at the state and local levels, including the California Office of Historic Preservation, the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation, San Antonio’s Westside Preservation Alliance, San Diego’s Chicano Park Steering Committee, the Blackwell School Alliance in Marfa, Texas, and many more.

The National Park Service will face daunting challenges in the years to come, but we still need its leadership, especially because we seek not only diversity and inclusivity in our national parks and preservation programs but also equity and justice. At the Chávez National Monument, this means the maintenance of an adequate budget, staffing and other support. Seven years after his appointment as superintendent, Ruben Andrade continues to manage the monument in partnership with the National Chávez Center and, recently, with support from the Latino Heritage Internship Program and from the National Park Foundation’s Mellon Public Humanities Postdoctoral Fellowship Program. Additional resources would allow for the further development of on-site and digital interpretation and other educational offerings.

Stay On Top of News

Our email newsletter shares the latest on parks.

In completing its “César Chávez Special Resource Study,” the Park Service also recommended federal support for the recognition, protection and interpretation of Forty Acres and the Filipino Hall in Delano, the former Guadalupe Mission Chapel in San José, the Santa Rita Center in Phoenix, and many other sites and properties that merit NHL designation or National Register listing.

Federal funding for such efforts is woefully inadequate. For every $100 the federal government allocated in its last budget, the National Park Service received seven pennies — a paltry amount to invest in the Park Service’s contributions to our local economies, our environmental and public health, our educational resources, and the strength of our social fabric.

Our federal government can do better, but so can we. The march must continue. Our future depends on it.

About the author

-

Ray Rast, Ph.D. Contributor

Ray Rast, Ph.D. ContributorRay Rast, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of History at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington, where he teaches courses in U.S. history, the history of the American West, American Latina/o history, and public history. He is proud to serve on the Board of Directors for Latinos in Heritage Conservation.

-

General

-

- NPCA Region:

- Pacific

-

Issues