Summer 2025

Battlefield Barkeologists

Hardworking canines are helping staff at Richmond National Battlefield Park identify the unmarked graves of enslaved people.

Last summer, a new sign appeared at Totopotomoy Creek Battlefield. “Attention,” it read, “Dogs Working.” The 124-acre site, part of Richmond National Battlefield Park, isn’t a stranger to four-legged visitors. At any given moment, a half dozen pups might be romping around this former plantation in central Virginia, human visitors in tow. The canine laborers this past June, however, were on a much different mission. They’d been deployed to seek traces of people buried on the property more than 150 years before.

Richmond National Battlefield Park’s 12 noncontiguous units preserve the Civil War-era structures, landscapes and history of this city (then the Confederate capital). Part of that story played out on what was once a 900-acre estate on the banks of Totopotomoy Creek known as Rural Plains. (The creek gets its name from Chief Totopotomoi, a 17th-century Pamunkey leader, whose people have a long history in the area.) As Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s forces marched toward Richmond during the Overland Campaign in 1864, Union and Confederate soldiers spent days advancing, retreating and jockeying for position along this tributary. Today, the site features a 1.5-mile trail that runs by a circa-1725 stone house, edges past agricultural fields and dips into the forest on its way to the water.

Visitors can easily find the graveyard for residents of the main house, which is set off by a white picket fence, but until recently no one knew precisely where the family’s enslaved workers were buried. (It was clear there had been another cemetery because a former landowner had mentioned its existence to park staff.) Tasked with searching a lot of land at a reasonable cost using minimal staff time, the park’s archaeologist, Lexie Lowe, started looking around for a method that wouldn’t disturb the ground.

Kristen Allen, the park’s integrated resources manager, said that they’d used ground-penetrating radar for other projects in the past, but that method proved unreliable and time-intensive on varied terrain. “Those things really have a hard time getting through the forest,” she said. For that technology to succeed in this situation, they needed a way to significantly narrow down the search area.

“The dogs seemed like a really good method to try out,” Lowe said.

Paul S. Martin with Abby. Martin is the founder of Martin Archaeology Consulting, LLC.

COURTESY OF PAUL MARTINSo, they contacted Paul S. Martin, the owner of an archaeology consulting firm that specializes in pairing highly tuned biological sensors (read: canines) with more traditional remote sensing methods. But unlike other human-remains-detection dogs, which might be trained to sniff out the scent of those who died within the last few decades, Martin’s dogs are trained to seek decomposition odors corresponding to historical, even pre-colonial, remains.

Martin said he fell into this line of work while volunteering with a sheriff’s office on a missing person case in 2002. He and his dog followed a tip about the man’s whereabouts to some Native American mounds in Mississippi and, amazingly, his pup started responding as if human remains were present, even though there was no evidence of a recent burial. He started wondering about the limits of canine olfaction. In other words, how far into the past could his buddy smell? “It opened up this whole line of research and questioning,” Martin said. He went back to school, eventually completed a master’s degree in anthropology and embarked on doctoral coursework with a focus on archaeological geophysics.

Today, his crew of handlers and their keen canines — coined “barkeologists” and “snoofers” — have traveled to sites in about two dozen states, including several national park units, and even overseas, where they’ve been involved in the search for World War II missing-in-action personnel. This work, Martin said, helps “provide recognition for those individuals who oftentimes have been forgotten.”

Working Like a Dog: See How Pups Help Park Rangers in These 12 Unusual Jobs

From sniffing out turtle eggs to keeping mountain goats out of parking lots, four-legged rangers carry out many duties that help preserve national park resources and make sure visitors have…

See more ›Environmental factors — such as extreme heat, wind and rain — can influence the perceptibility of smells. But in most cases, Martin said, the ideal time for pups to put their noses to the dirt is early in the morning, just as the sun is heating the ground. Such was the case at Richmond National Battlefield Park, where Martin and his dog Abby, as well as veterinarian Kathleen Connor and her pup Seamus, worked two different sites for around four hours a day over the course of about two weeks. Equipped with GPS-enabled collars, Abby and Seamus crisscrossed 15 acres of uneven and bramble-studded land at Totopotomoy Creek and Glendale, another former plantation in the park. Martin used a laptop to track the dogs’ somewhat erratic paths, building a map of everywhere the Labrador retrievers had run. This information helped him identify any gaps in the canines’ coverage, which the teams surveyed on subsequent days.

“The dog is not just running everywhere,” Martin said. “To the untrained eye, it might look like that. But it’s very much a controlled process, very much like two dancers, in that the handler will react to what the dog does, and the dog will react to what the handler does.”

Even highly trained barkeologists need the occasional break, though, as demonstrated by Abby. “She’s very friendly through the whole thing,” Lowe said. “She’ll come up, say hi, and then go back to work.”

Allen and Lowe invited cultural resources staff from other parks and Tribal partners out to see this non-invasive technique in action. Martin would explain the whys and wherefores of the process, and then they all observed as one of the pups traversed the land.

To everyone’s delight, the doggy gamble paid off. Allen described being on hand to witness the canines suddenly stop, seemingly apropos of nothing, and either bark or sit to indicate they’d smelled what they’d been trained to identify. The experience was “very powerful,” she said. All told, Abby and Seamus alerted their handlers several times at both sites (receiving the occasional treat, toy or praise), but those responses don’t necessarily signify the presence of discrete graves. Rather, their signals are an indication that the particulars of the topography and climate have funneled decomposition odors into that spot.

To confirm the dogs’ finds, Martin used ground-penetrating radar soon after Abby or Seamus detected something and then returned in the fall to perform magnetometry, which maps underground features based on their effect on the geomagnetic field, on the identified hot spots. After synthesizing the disparate datasets, he pinpointed multiple burial locations. (In an effort to preserve the integrity of these archaeological sites, neither the Park Service nor Martin would disclose the exact number or location of these finds.)

Bird’s Best Friend

Turning to the very goodest dog in the race to save Hawaii’s endangered seabirds.

See more ›In time, Lowe and Allen hope the park can honor the final resting place of all those who once stewarded the land. “We want to tell more stories and represent a more complete history of these battlefield landscapes,” Lowe said, “because the history is a lot deeper than just the time periods of the Civil War battles.” They would like to collaborate with the descendants of those buried on the properties and explore their ideas for how to commemorate and honor their ancestors. To that end, they recruited Orice Jenkins, a genealogist from New England with a personal connection to Rural Plains, to investigate who might have lived and labored at the plantation.

Jenkins first happened upon this Hanover County estate about five years ago while digging into his family tree. He was most curious about his maternal grandmother’s ancestry, as she’d been his best friend, so he’d been following that line back in time as far as he could go using DNA, as well as historical records. He wound up in the 1700s, in the Richmond area of Virginia. More specifically, he traced his ancestors to plantations owned by the sons of John Shelton, the original owner of Rural Plains. Through his research, Jenkins discovered that a man by the name of Bristol, likely the father of his seventh great-grandmother, might have been born at Rural Plains.

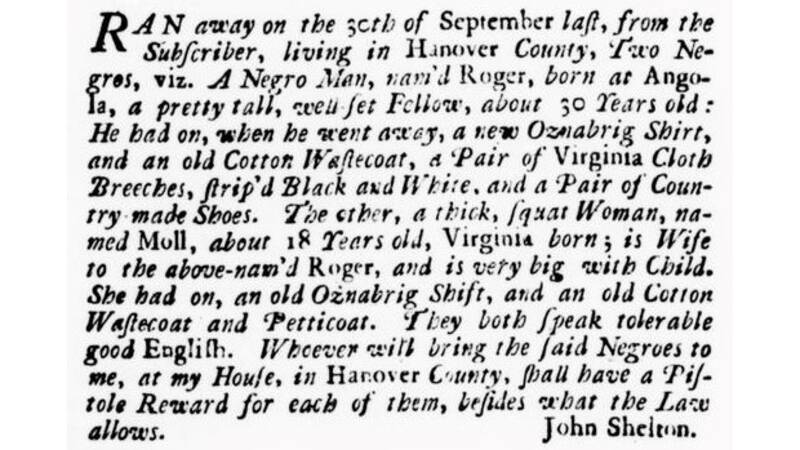

While researching those who had been enslaved at Rural Plains, genealogist Orice Jenkins discovered this advertisement requesting the return of two people who had escaped.

COURTESY OF ORICE JENKINSIntrigued, Jenkins visited the park and eventually connected with a few rangers. When the opportunity arose for the park to hire someone to assist with genealogical research, Jenkins seemed like a natural fit. He was well aware of the project’s complexities. Not only was the search itself tricky — after all, enslaved people are generally nameless outside of probate inventories, which itemize property assets — but many of the records he would have used had been destroyed when the Confederacy set fire to Richmond in 1865. Undaunted, Jenkins pivoted to other sources, and his perseverance was rewarded. “Altogether, I was able to identify around 90 distinct names of people that were enslaved on the land between 1739 and 1865,” he said. One of his most interesting discoveries was a nearly 200-year-old advertisement listing two people, Roger and Moll, who fled Rural Plains (or possibly one of the landowner’s other properties) and ran away together. “I’m hoping that they escaped somewhere where they could be free,” Jenkins said.

His goal for this research mirrors that of the park staff. “I just want to see these people remembered,” he said. “I have trouble saying John Shelton built Rural Plains, because I don’t think he did. I think the people that he enslaved, they’re the ones who labored to build that house and to clear those fields and to plant those crops. So, I want their names to be remembered and to be called out and to be memorialized in some kind of way.”

About the author

-

Katherine DeGroff Associate and Online Editor

Katherine DeGroff Associate and Online EditorKatherine is the associate editor of National Parks magazine. Before joining NPCA, Katherine monitored easements at land trusts in Virginia and New Mexico, encouraged bear-aware behavior at Grand Teton National Park, and served as a naturalist for a small environmental education organization in the heart of the Colorado Rockies.