Fall 2015

Gift of the Glaciers

Michigan’s Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore offers visitors beaches, bluffs, clear waters, and 10,000-year-old hills of sand.

The crooked letters on the hand-painted sign stand a foot high, broadcasting a surprising message to everyone driving past the produce stall filled with ripe cherries. Instead of advertising pie or pints of fruit, they advise, “Live the Life You’ve Imagined.” It’s a sentiment off a coffee cup, but in this unexpected setting, it doesn’t strike me as trite. Instead, it reminds me that I’m visiting a place that haunts my own imagination—the northern shores of the Great Lakes.

A Petoskey stone, a fossil found only in Northern Michigan.

© IAN SHIVEI’m driving toward Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore in northern Michigan. I spent a season as a camp counselor in the woods nearby one distant summer, and ever since, I’ve dreamed about cackling loons, lighthouse beams winking over the water, and white bark peeling off birch trees—the sights and sounds that capture the spirit of the wild north for me. Thirty years ago, I only had time to drive through this park. This time around, I want to savor it. I pass cars with green canoes strapped to their roofs, reminding me of the fur traders and Native Americans who once paddled the lakes. In fact, it was the Anishinaabek Indians who gave the dunes their name.

TRAVEL ESSENTIALS

According to their legend, a blazing forest fire on the shores of Lake Michigan once forced a mother bear and her two cubs into the water. When the mother bear reached the opposite shore, she looked back to discover that her cubs had drowned just before reaching land. The grieving mother was transformed into a giant sand dune, and her two cubs became the twin Manitou Islands.

Geologists tell a different story, one that’s dominated by another towering figure: the glacier. More than 10,000 years ago, an ice sheet a mile thick made its way down a series of ancient river valleys, gouging out the Great Lakes. Then the bulldozer of ice melted away, leaving pulverized rock behind in the forms of hills and bluffs on the lakeshore. Winds blowing across Lake Michigan lifted the finest particles of rock to the top of these bluffs, creating perched sand dunes. Today, dunes like these are found in only a handful of places on the planet.

I arrive in mid-July, the height of vacation season, looking for two things I fear might be elusive at this time of year: some peace and quiet, and a Petoskey stone. The stones are fossils that can be found only in northern Michigan, the remains of a massive coral reef. The skeletons of six-sided coral polyps that lived 350 million years ago leave ghostly white lines on the smooth gray rocks. It’s legal to collect Petoskey stones on most beaches in the state. Even though the fossils inside the park are protected, I still wanted the thrill of winning my own scavenger hunt.

Arriving late in the day, I begin my quest for quiet at the short Pyramid Point Trail. When I pull in around dinnertime, the trailhead is nearly empty, which seems like a good omen. The trail begins in a meadow of wildflowers but soon climbs through a maple and birch forest that reminds me of those mainstays of northern souvenir shops, maple syrup and birch bark canoes. I break through the trees to find myself on top of a dune that drops nearly straight down to the water below. I’m 400 feet above Lake Michigan on a sandy grandstand. The sun sparkles off a lake that stretches to the horizon, looking vast as an ocean, and a tiny Great Lakes freighter threads its way between the shore and the Manitou Islands, hazy green in the distance. This treacherous stretch of water, known as the Manitou Passage, has snared dozens of ships over the years. (The Maritime Museum in Glen Haven Historic Village, a few miles south of my lookout, holds daily demonstrations showing how locals once rescued the victims of Lake Michigan shipwrecks.)

Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore

Sleeping Bear Dunes features immense and magnificent sand dunes, as well as beaches, forests and inland lakes along a 35-mile strip of the southeastern shore of Lake Michigan. Off the…

See more ›I hadn’t planned to linger for long, but with my toes burrowed into warm sand, I listen to the measured slap of waves hitting the beach below, punctuated by the bass notes of a foghorn. The sounds lull me into watching the ship until it disappears into the blue—shipwreck safely avoided. Back on the path, three pileated woodpeckers, each a foot and a half tall, flash across the trail just a few yards away. I’d seen taxidermied versions in the visitor center and marveled at their size, and now I could tell that an enormous woodpecker doesn’t actually flit—it seems to lumber through the air, like a duck wearing a backpack. Having sighted one cool bird, I check my birding brochure: that’s one park species down, and 285 left to go.

The next morning, I head for the park’s scenic drive to get an overview of the landscape. The drive is slotted into one of the widest sections of a mostly skinny park that hugs the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. When Sleeping Bear was established in 1970, it already had a long human history, starting with Native Americans tapping maple trees for sugar. French Jesuits arrived in canoes in 1675, then Europeans moved to the area to cut timber for steamships plying the Great Lakes. They were followed by farmers, and finally by nature lovers building vacation cottages and homes. As a result, the lakeshore is a patchwork of park and private land, and the park’s main road weaves in and out of villages, meandering past old wooden barns and cherry orchards filled with fruit.

SIDE TRIP

The scenic drive loops through the maple forest and emerges on top of four square miles of sand dunes, an expanse that connects to the body of the legend’s sleeping bear. The Cottonwood Trail is the only path onto the dunes, and hiking along its weathered gray boardwalks, I discover that these dunes are no arid Sahara but an oasis of life. Cottonwood trees shade the path, their leaves rattling in the breeze off the lake. A hognose snake skitters through the coarse grass, leaving an S-shaped track in its wake, and strangest of all, wide swaths of sand are blanketed by the tiny white flowers of baby’s breath, the same plant that florists use in bouquets. I enjoy the sweet smell until I meet park ranger Peggy Berman, out on patrol. She tells me the flowers escaped from a nearby garden 30 years ago and have taken over wide sections of the dunes. The delicate blossoms are anchored by a gnarled root bigger than my forearm, which lodges them in place. These roots are harming the dunes by preventing them from naturally drifting over time. It’s a reminder of the fragility of this rare ecosystem, which sits cheek by jowl with civilization and its gardens.

Dumping sand from a sneaker after climbing a dune.

© IAN SHIVEAlthough the dunes are fragile, there’s something about a giant hill of sand that begs to be climbed. The park’s Dune Climb, about five miles north of the village of Empire, scratches that itch with a 110-foot-high dune that kids, or anyone who can’t resist the sight of all that sand, can climb up and then descend at top speed, yelling optional. The dune has actually shrunk over time, as visitors cart it away grain by grain in their shoes.

So far, my hikes have taken me to the tops of the dunes, high above Lake Michigan itself. But if I want to hunt for a Petoskey stone, I need to find a beach. A tip leads me to the Sleeping Bear Point trailhead, where a path veers away from the parking lot toward the lake. I wind my way between two steep dunes, wondering if I’m lost, then suddenly emerge on a wide sweep of empty beach. In the distance, a figure hunches over in the surf, searching for something in the water. It takes five minutes of walking over the cool, damp sand to reach the man, who is peering through the clear water, picking up smooth beach stones and chucking them back in. A pile of his favorites rest nearby. “These are just pretty rocks,” he explains, “except for this one.” He pulls a gray stone out of the pile. “This one’s a Petoskey. They’re easier to spot if you look underwater.” It had taken him about an hour of searching, he said, to come across his find. One hour later, I don’t have a single fossil, but I’ve got my own pile of pretty rocks, wrinkly feet, and the kind of serenity that can be improved only by something even more blissful—like a slice of Michigan cherry pie from a local bakery.

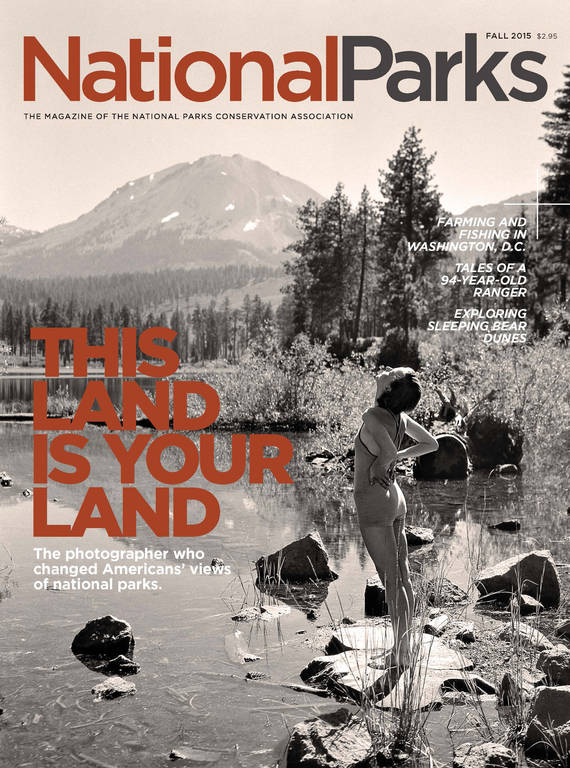

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›I think I’ve found Sleeping Bear’s most out-of-the way beach, but I’m wrong. The next day my husband joins me, and we set out for one of the park’s jewels, isolated South Manitou Island, reachable only by an 80-minute ferry ride. The island has no permanent residents and no cars, but its former inhabitants left behind a tall white lighthouse, a one-room school, and a picturesque cemetery. I take the Manitou Island Transit ferry on a Friday morning with a few dozen weekend backpackers bound for the island’s campgrounds, but once they disappear into the woods, we seem to have the place to ourselves. We sit on the steps of the 1871 lighthouse, eating lunch and watching swallows swoop over the waves, snatching insects from the air. Once a minute, as if on schedule, a line of double-breasted cormorants skims past. Perhaps they’re flying to the shipwreck we spot later, where roosting birds cover the rusting hulk of the Francisco Morazán. Five hours after we arrive, which seems far too soon, we hike back to the ferry dock. While the boat motors into sight, I search the shoreline one last time for the flash of mottled gray that signals a Petoskey stone. I board the ferry with empty pockets but the realization that I have, after all, found an excellent prize: a reason to come back to Sleeping Bear next year.

IAN SHIVE is a photographer, author, film and television producer, and conservationist. His latest book, Celebrating the National Park Centennial, will be released in November.

About the author

-

Laurie McClellan Author

Laurie McClellan AuthorLAURIE MCCLELLAN is a freelance writer who grew up on the southern shores of Lake Michigan. She loves maple syrup and anything made out of birch bark, and has hiked in more than 20 national parks.