Summer 2024

Four Walks in the Park

When I decided to camp four nights over four seasons in Rocky Mountain, I hoped for some time alone in the woods. I got that — plus a snowstorm almost too big to handle.

Ice crystals on the inside walls of the tent shimmered in the light of my headlamp. I checked my phone, which I had kept in my sleeping bag so that the battery wouldn’t freeze: 5:30 a.m. I sat up and tapped the nylon, expecting a layer of light snow to glide down, but instead the fabric felt heavy to the touch. Uh-oh. I anxiously unzipped the door, and a mini-avalanche tumbled into the tent.

I put on my snow boots and dug my way out. It was pitch-black, and snowflakes pelted my face. From the outside, the tent looked like an igloo with an orange crest, and I wondered whether I’d be able to find the trail leading back to my car under 3 feet of snow. My “breakfast skillet” dehydrated meal would have to wait. I had to get out of there.

This was not what I had in mind when I first set out to camp in the Wild Basin of Rocky Mountain National Park. My original inspiration was “A Year in the Woods: Twelve Small Journeys into Nature,” a small book by Torbjørn Ekelund that I received as a gift a couple of years ago. In it, Ekelund laments about how the incessant demands of daily life have kept him from experiencing the simple joys of nature, so he decides to leave his house after lunch once a month for a year and spend the night by a small pond in a forest near his Oslo home. His idea was that with no one around and nothing to do, he could pay attention to the subtle changes that mark the passage of seasons. “We most clearly perceive nature in these transitions, and yet they are also the easiest things to miss because they most often occur in the most minuscule of moments,” he writes. “To experience them requires stillness and attention as well as an openness to one’s surroundings.”

I could relate to Ekelund’s yearnings. I know about the countless benefits of spending time in nature, but work deadlines, grocery shopping and carpools to kid activities have a way of taking precedence over walks outside. What I lacked was intentionality, so the idea of setting aside a few dates to be out in nature was appealing. I was not even done reading Ekelund’s book when I decided to emulate him: I’d camp four nights — one in each season — in the same spot of Rocky Mountain. Ekelund had boldly started his year in the woods in January, but I figured I’d ease into it. I’d begin with spring and work my way toward winter.

While Rocky Mountain is not exactly in my backyard, some of its trailheads are less than an hour away from my home in Boulder, Colorado. Wild Basin was an obvious choice for my “micro-expeditions,” as Ekelund calls them. It sees relatively few visitors, and that park entrance is the closest to me, which was important because, like Ekelund, I’d arrange to leave home each time after a shortish workday and be back at my desk the next morning. I wasn’t sure these interludes of solitude would be long enough to recharge, but I intended to make the most of them.

I had never been to Wild Basin before, but I settled on the Campers Creek campsite. It’s about 2.3 miles from the trailhead, so I could get there and back reasonably quickly. From what I could tell, the campsite was not by a lake and didn’t offer any sweeping views, which I hoped meant less competition to book the site. Nonetheless, I was ready when the reservation period opened in March, and in a matter of minutes I had booked the site for spring, summer and fall.

Spring

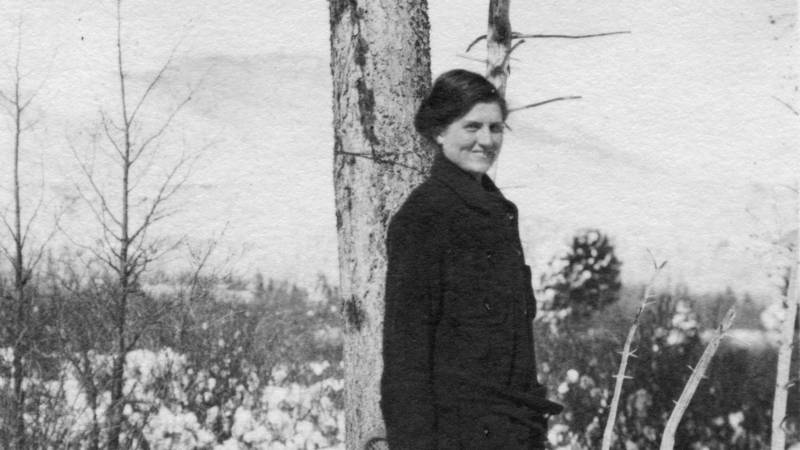

Esther of the Rockies

She left the corporate world to homestead in the mountains and became the Park Service’s first female nature guide.

See more ›What is spring? Astronomically speaking, it begins on the equinox around March 20, when day and night are each about 12 hours long. I associate spring with pretty little flowers, but you would be hard-pressed to find a blossom anywhere in Rocky Mountain in late March. The park’s wilderness camping page provides a useful factoid for each of its campsites: what it calls the 20-year average snow-free date. For Campers Creek, that date was June 5, so I had picked June 6 and hoped for the best. On the day, I belatedly realized that to get my permit, I had to go to the park’s wilderness office, which closed at 3:30 p.m. and required a significant detour. As I drove, the skies went from a welcoming azure to an ominous slate hue. The ranger at the wilderness office told me a thunderstorm was expected that night, and he gave me another tidbit to chew on: a black bear had just been spotted near my destination. “They’re definitely out and about right now,” he said, as a screen behind him displayed images of bears getting into all kinds of mischief. “They’re waking up from the wintertime. They’re definitely hungry.”

Paying attention to the little things usually requires discipline on my part, but it was easy when I first started hiking. The ground was littered with brown, brittle pine needles, yet new life shot through in the form of yellow, blue and purple flowers that my phone’s plant identification app later informed me were thermopsis, clematis and mertensia. Bell-shaped white blooms on berry bushes and moth cocoons held the promise of even more changes to come. With every step, soft patch of moss and interesting lichen pattern, my mood brightened, and I stopped to snap pictures. My worries about a rain-soaked outing dissipated as the sun emerged and rays filtered through the ponderosas.

The straps of my overloaded backpack started to dig into my shoulders over time, though, and thoughts of unfinished tasks started creeping back in. So it was with some relief that, a little less than two hours after leaving my car, I spotted the sign for the turnout to Campers Creek. I followed a muddy path to a clearing amid towering spruce, which would be my home for the night and others in the months ahead. I dropped my heavy pack, set up camp away from the rain puddles and placed my bear-proof canister a safe distance away. Since there was quite a bit of daylight left, I decided to walk another couple of miles up to Sandbeach Lake, a destination the ranger had recommended.

Hiking up was like going back in time. By the trailhead, aspens sported bright green leaves, but higher, leaves were smaller, then there were no leaves at all, and finally there were no more aspens. The broad-tailed hummingbirds I’d seen earlier were gone, and I encountered patches of crusty snow, which eventually covered the trail.

View from the author’s campsite in the spring.

Nicolas BrulliardBecause the whole hike had been a walk through the woods, it was somewhat of a shock to arrive at the lake where I was afforded a 360-degree view. The still water was ringed with conifers and a few stands of willows, and all around me, gently sloping peaks dotted the horizon. I couldn’t believe I had the whole place to myself. I sat down on a granite boulder jutting out into the water, ate a salami sandwich and lingered as daylight started to fade.

It was past 9 by the time I was back at my tent. I attempted to read my book for a few minutes and conked out. It turns out that early-June nights at nearly 10,000 feet can be quite frigid. Despite wearing all my layers, I struggled to get warm. I got up before dawn and couldn’t eat breakfast because my canister, I discovered, not only is bear-proof but also resisted my cold and numb fingers. By the time I was done packing, the day’s first beams of sunlight had turned the tips of the spruce trees a greenish gold. I was about to hike out when I noticed, a few feet away, what I can best describe as a miniature throne delicately fashioned out of moss, pieces of wood and pinecones. Either my ability to pay attention to small things was worse than I thought, or I’d have to reconsider my take on the existence of forest fairies. I was back at the trailhead before 7:30 a.m., and it was there that I saw the first humans since I’d left the car the day before.

Summer

Trip two in mid-August had the comforting feel of a personal tradition. I now knew when and where to pick up my permit and how long the hike in would take. I was greeted by the same friendly ranger at the wilderness office who gave me the same warning about a “big burly black bear.”

The Long Haul

For more than four decades, Jill Baron has studied the changes to the air and water quality of a small corner of Rocky Mountain National Park, and her research exposed…

See more ›Some changes were immediately apparent. It was considerably balmier, and the warm air carried the scent of pine needles. Also, the parking lot and the trail were more crowded. Wildflowers were less abundant but tended to be larger, and bees swarmed around purple asters and thistles. Gone was the chirp of hummingbirds, but the buzz of grasshoppers provided the new soundtrack to much of my hike. The narrow path to the campsite was now lined with ferns, and the fairy throne was in ruins. After setting up camp amid a swirl of mosquitoes, I decided to go back to the lake — both to take in the view and escape the blood-thirsty bugs.

The scene at the lake was no longer a surprise, but it was breathtaking nonetheless. The snow had melted away, and little white clumps of western pearly everlasting flowers had bloomed by the shore. I encountered one solo camper and a couple, but we kept our distance. Above me, contrails streaked the sky, and I wondered if true wilderness still existed anywhere. I quickly ate a snack on the same rock I’d sat on the last time and headed back to my tent.

I woke up at an ungodly hour because I was on a mission. When I had booked my summer outing months earlier, I hadn’t realized it would coincide with my daughters’ first day of school, but if I packed up quickly and kept a steady pace on the trail, I’d be home in time to walk them to class. I felt pretty good about myself when I got in the car before 7 and was downright buoyant after spotting four bighorn sheep on the drive. But all that cheeriness disappeared when I passed the school and saw all the parents walking away. I had somehow missed the notice that school was to start an hour early that day, and all my planning had been for naught.

Sandbeach Lake.

Nicolas BrulliardSpring foliage.

Nicolas BrulliardSunrise over Colorado’s Front Range.

Nicolas BrulliardSandbeach Lake trail.

Nicolas BrulliardFall

I never expected my camping trips to be affected by the shenanigans in Congress, but as the October 3 date of my fall outing approached, the likelihood of a government shutdown on October 1 seemed to increase by the day. If the federal government closed, national parks would likely shutter, too, and if they did, who knew how long it would last? Not willing to risk it, I called the wilderness office on September 26 to see if Campers Creek was available that night. It was, so I hurriedly packed my bag and headed to the park.

In early fall, Rocky Mountain is the stage for two star performances: elk bugling and aspen leaves turning golden. I knew I’d be more likely to see elk in nearby Estes Park than on my hike to Campers Creek (and I did in fact see them all over town), but I was hoping to catch the aspen spectacle. It didn’t take long for my hopes to be dashed. In each aspen cluster I saw on the trail, the trees had already lost their leaves or the holdouts were mottled with black and gray spots. Someone on a passing trail crew said abundant rains in the spring were the culprit, while his crewmate blamed abrupt weather changes. “It’s just a guess, though,” he said.

Because aspens are pretty much the only deciduous trees along the trail to Campers Creek, I had to search for fall colors among shrubs, vines and small plants. It was a diminutive yet stunning show of scarlet, canary and tangerine shades, sometimes all in one leaf. The air was chillier, and more than once I caught a whiff of mushrooms. One change that was inescapable was a shorter day, so I hurried to my campsite to pitch my tent. Back on the trail to the lake, I heard a ruffling noise and turned to face a male deer sporting a rack the size of a small chandelier. He gave me a quick glance before darting into the brush.

It was dusk by the time I made it to the lake. I was threading my way toward my usual rock through dense stands of head-high willows when I stopped in my tracks. About 25 yards in front of me was an antlerless moose the size of a horse. It appeared almost black in the fading light, except for its gray legs and a tuft of white on its rump. I’d learn later that moose are not native to Colorado, but this one looked right at home, unwilling to cede an inch of its territory. We looked at each other for a long while, then it lost interest and started munching on grasses. I stayed a few more minutes, then bade it farewell and retreated.

Fall fireweed.

Nicolas BrulliardAfter encountering two large mammals, I found myself thinking about mountain lions the whole way back to the tent. At first, I imagined how cool it would be to spot one of America’s most elusive predators. But as darkness fell and the battery of my headlamp weakened, I started to envision what would happen if one of these gorgeous cats decided to prey on me. I picked up a good-sized rock and a stick. Just in case.

There is something soothing about packing up your tent. It involves steps that have to be performed in a certain order, and it’s not a task you can leave for later, like filing expenses. I was also starting to enjoy the routine of the morning hike back to the car. It was downhill, for one thing. And completing an hourlong hike in a national park before many people had had their first cup of coffee made me feel like the day stretched out ahead of me was full of possibilities.

Winter

There is no such thing as spring, summer or fall camping but winter camping is a thing. In fact, in anticipation of my trip, I picked up not one but two “winter camping” guides at the library. In these books, I read about interesting skills, such as how to make a “deadman,” which is a sort of anchor for your tent when you camp on snow, and unsettling winter hazards, from snow blindness and chilblains to sun bumps and Raynaud’s syndrome. I also figured out that I needed to up my gear game. I had shivered each night so far, so my 22-year-old sleeping bag was not going to cut it, and my so-called three-season tent wouldn’t do either. “Winter is the one season where your gear really makes a difference between comfort and misery, or even survival,” wrote Molly Absolon in “Winter Camping Skills.” I wanted comfort, and I certainly wanted survival. My wife had given me a “zero-degree” sleeping bag for Christmas, and I settled on a mountaineering tent called the HotBox. I really hoped it would live up to its name.

Snowed In

Surviving a winter in Glacier National Park takes a strong marriage—and 25 pounds of coffee.

See more ›One of my library books recommended that winter camping newbies pick a day after a snowstorm for their first outing. Based on forecasts, March 13 seemed promising, but as the date neared, it looked increasingly likely that I’d be camping in a snowstorm. When I showed up at the wilderness office, though, gray skies were distilling just a few meager snowflakes, and I reasoned that if conditions worsened significantly, I could always scrap my camping plans. I told the ranger who handed me my permit as much, and it seemed to reassure her — somewhat. “We’re totally OK with you going out there during a blizzard because this is your park and you have the ability to go wherever you want,” she said. “But that doesn’t mean we aren’t going to worry about you.” She told me that no one else had requested a camping permit and that the park would probably shut down the next day. “Just know that it will be you out there, and that’s it,” she said.

There was almost no snow on the ground by the time I started hiking a little after 2 p.m. I saw some hikers in jeans and tennis shoes. This was hardly the setting for impending doom, I thought, but as I went up, I encountered both more residual snow from earlier snowfalls and more fresh accumulation. Before long, a layer of white covered everything.

The park asks backcountry campers to avoid designated tent sites if there is more than 4 inches of snow on the ground, so I picked a flat-ish spot in the vicinity of Campers Creek. Fallen trunks lay in a nearby jumble and a dead spruce tree stood uncomfortably close, though after side-eyeing it, I decided it wasn’t a potential widow maker. I strapped on my snowshoes, packed the snow to create a pad and pitched my tent. It was still early, and I wondered what the lake looked like in winter — and if I could make it there. I decided to give it a try.

Snow-covered spruce branch.

Nicolas BrulliardThe fresh snow turned every tree stump and rock into smooth, white humps. I spotted my first-ever snowshoe hare before it hopped away. The only other creature I saw was a brave little spider traipsing on top of the snow cover. I relished the quiet that had descended on Wild Basin, and the snow felt like an ally rather than a menace. Daylight was fading when I made it to a frozen and snow-covered Sandbeach Lake. I could barely make out the far shore of the lake, and anything beyond disappeared into the whiteness.

There is a fine line between solitude and loneliness. As full darkness set in, I started gravitating toward the latter before the increasingly snowy path demanded my full attention. Back at my tent, I slipped into my warm sleeping bag and wondered about what the next day would bring.

When I surveyed the snowy scene the next morning, I briefly considered leaving my igloo-tent behind and coming back later to get it. After thinking better of it, I used a snowshoe as a shovel to dig out the tent, which took me most of an hour.

There is such a thing as too much snow for snowshoes — or at least my snowshoes. I found myself knee-deep in the powder, and each step involved lifting not only my foot, but a big pile of snow on top of it. I had to catch my breath every minute or so. Also, the trail was nowhere to be seen. I kept straying from the path I thought I knew and tripping over snow-covered tree trunks and rocks. After three and a half hours, I finally made it to the parking lot — now a vast white plain from which protruded a boulder-sized mound where my car had been.

There is a fine line between solitude and loneliness.

I got to work shoveling my car out, but after two hours I had moved it only 10 yards — and the county road was still an additional 100 yards away. I needed to let my wife know I wouldn’t make it home that day, but one of Wild Basin’s wildness attributes is that there is virtually no cell service, so I walked toward a few houses nearby hoping that someone would let me use their phone. Most were clearly vacant. I found one with a couple of snow-covered cars outside and knocked on the door, but no one answered. Finally, I spotted a house with snow-free cars — and light inside. The owners, a couple, were understandably wary at first, but they let me use their landline, and then generously offered me their guest bedroom for the night. The husband told me he hadn’t experienced as big a snowstorm in a couple of years, which both validated my experience and put my judgment into question.

Crossing a stream in snowshoes is a perilous exercise.

Nicolas BrulliardThe park had closed, and there was no information as to when the trailhead parking lot would be plowed, so I figured I might as well continue to work at clearing a path for my car even though the snow was still falling. I borrowed a snow shovel and dug for four hours before calling it a night. After sharing a glass of wine with my hosts, I showered and, exhausted, crawled into bed. It was my best night’s sleep in recent memory. The snowfall had finally stopped by the time I walked back to my car at 7 the next morning. I toiled for a few more hours, then caught a break when I convinced the operator of a county snowplow to clear a section of the park road even though it was outside his jurisdiction. My car was still struggling to get a grip on the soft snow, but around 11, a park ranger showed up. He offered to give my car a push, and just like that, the car lurched forward, and I was on my way home. It almost didn’t feel real to be effortlessly zooming at 55 mph on clear roads.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›What did these four nights in the wilderness get me? They did allow me to escape the ever-present worries of daily life, but I was never out there long enough to achieve a state of reverie à la Thoreau. My Walden Pond was a destination rather than an inspiration, and I found myself spending much of my time on the move, hiking in and out, setting up camp and taking it down. I did find instances of ordinary and extraordinary beauty, though, in the snowy pom-poms on pine branches or the soothing chomp of a moose at ease with my presence. I also found solitude, that elusive quality in increasingly crowded national parks.

After I returned from my winter trip, I was somewhat miffed not to be peppered with questions from my family. I had just camped alone in the year’s biggest snowstorm, trudged through snow up to my waist and gone on a two-day shoveling marathon. How could they not want to know everything? But then I came to see that this was precisely the reason I had ventured out by myself: Yes, I could attempt to share my stories, but in the end, the experiences and memories would be mine and mine alone.

About the author

-

Nicolas Brulliard Senior Editor

Nicolas Brulliard Senior EditorNicolas is a journalist and former geologist who joined NPCA in November 2015. He serves as senior editor of National Parks magazine.