Spring 2024

A Diamond in the Desert

During World War II, Japanese Americans held at Manzanar found joy and normalcy in baseball. More than 80 years later, their field is back.

Sometimes history needs to be unearthed, and other times it just has to be weeded.

That’s what 27 volunteers gathered to do last November at the Manzanar National Historic Site in California’s Mojave Desert. The volunteers arrived to find 3 acres of tumbleweed that the National Park Service had marked for clearing. Buried beneath the brush was a baseball field where more than 80 years ago, Japanese Americans imprisoned during World War II found escape and normalcy by playing ball.

The manual labor was arduous, even for Mike Furutani, who lives on a flower nursery near Salinas and is accustomed to toiling under the sun. “Clearing the field by hand gives you a perspective of what the internees did back in the day,” said Furutani, whose uncles and grandfather were imprisoned in a similar camp in Wyoming. “They did it all by hand, too. They must’ve really loved baseball, like I do.”

The volunteers worked all weekend under the shadow of a guard tower, using picks, shovels, rakes and pitchforks to clear brush. By the time they were finished, tumbleweed piles — some taller than a person — were scattered across the field. “It reminded me of the barbed wire fences,” Furutani said.

The ground was still uneven, but with boxes marking the bases, the field started to resemble the original. Furutani, who plays for and manages a Japanese American baseball team in Monterey, threw a few pitches from the mound. That’s when the weight of the whole thing hit him. “I was thinking about the guys who had stood here before me,” he said. “Baseball was their last hold on that belief that they were still Americans.”

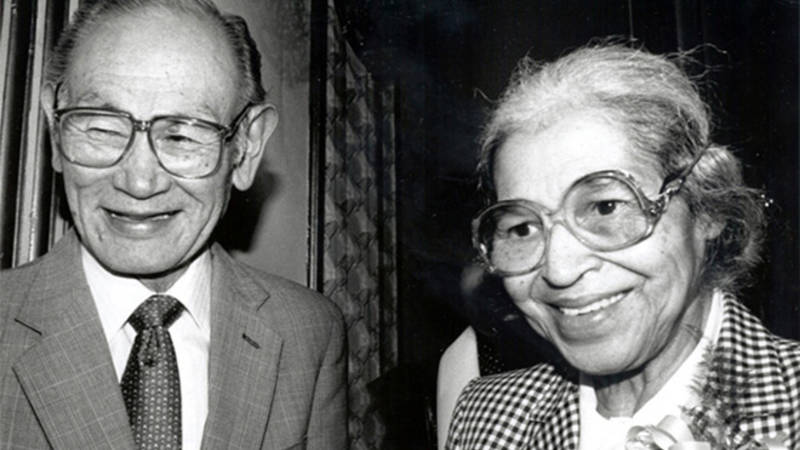

The Legacy of Fred Korematsu

He fought against his forced imprisonment, all the way to the Supreme Court. Today, the National Park Service helps interpret the dark history behind World War II incarceration camps.

See more ›The Manzanar War Relocation Center was one of 10 incarceration camps where the U.S. government imprisoned approximately 120,000 people of Japanese descent from 1942 to 1946. Manzanar was a desolate, inhospitable place where summer temperatures could top 110 degrees and winters were bitterly cold. Strong winds would cake the camp in dust. Two-thirds of the 10,000-plus people confined at Manzanar were U.S. citizens, and the remainder were barred from naturalization because of their race. Those imprisoned there had no idea how long they would have to stay.

In the face of injustice, the residents of the camp made a community in the desert. They built gardens, established a newspaper, raised livestock and made furniture. The camp operated like a small town, with its own bank, barbershop and general store. Sports were a welcome distraction, and baseball took on special significance. Manzanar formed 12 baseball leagues with more than 100 teams whose games, on the camp’s main field, drew thousands of spectators.

Manzanar ranger Sarah Bone said the Park Service and volunteers have long wanted to reconstruct the field, a project made possible in part by a grant from The Fund for People in Parks. She hopes future visitors will be able to play ball the way incarcerees once did.

Baseball was their last hold on that belief that they were still Americans.

“It makes that literal connection, that human connection,” she said. “No matter what your background is, you’re a human being playing sports behind barbed wire.”

Dan Kwong, whose mother, uncles, grandmother and grandfather were imprisoned at Manzanar, said his mother played catcher on a softball team there and once busted her nose when a hitter threw her bat. A performance artist, playwright and documentary producer from Los Angeles, Kwong has played in California’s Japanese American baseball leagues since 1971. These leagues, which began in Hawaii in 1899 then spread across the West, let people of Japanese descent pursue their love of baseball in a country that didn’t always welcome them. Kwong was thrilled to get the email from Park Service staff about the plan to use archival photographs to re-create the field and offered to head up the volunteer effort. Now he’s consulting with structural engineering and construction companies that are donating services to help build the backstop, fencing, announcer’s booth, bleachers and player benches.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Kwong wants to finish the field for several reasons. In addition to his commitment to telling the Manzanar story — he’s been visiting since childhood and volunteering since 2008 — he has been dreaming up a special day of baseball he’s tentatively planning for September. It will be a double-header, with the first game between the Li’l Tokio Giants and Lodi JACL Templars, the two longest continuously active teams in Japanese American baseball. The second game will be an all-star game, a North vs. South matchup of California’s top Japanese American league players. Kwong is raising money for that game to be played in 1940s-era uniforms with old-fashioned bats, gloves and gear. “It’s going to be like time travel,” he said.

Kwong continues to be inspired by the way his family and other Japanese Americans made the best of their terrible circumstances in the years they spent in incarceration camps. He credits their resilience to the Japanese value of “shikata ga nai,” which translates to “it can’t be helped.”

“It’s part of a cultural stoicism that helps people to move on from difficult things,” Kwong said. “The spirit of the community was, ‘You can stick us out here in the middle of nowhere, but we’re gonna live. We’re gonna live life. We’re gonna play baseball.”