Spring 2024

Rocky Days

How Chiricahua National Monument’s hoodoos and history helped one writer find her footing in the great outdoors.

I slowed the car and peered at the unassuming sign: “No services.” Six weeks prior, I’d suffered a life-threatening infection that resulted in a stint in intensive care, so this felt like a “here be dragons” challenge and warning in one. The prickle of unease was especially acute given that the illness had taken hold during my last camping adventure, and here I was, about to embark on another one.

The message’s location perplexed me, though. Wouldn’t a better spot for such a sign have been miles back, well before our arrival at Chiricahua National Monument? Say, sometime after my friend Andrea and I turned off the interstate from Tucson but before our surroundings assumed an almost fantastical severity? In that pocket of timelessness between departure and destination, we’d driven south through a seared and yawning valley, our view framed by the crenellated ridgelines of the Dragoon and Dos Cabezas mountains. The empty road, hazy with heat on that late October day, had dipped through arroyo after arroyo. Above, raptors perched on power lines, their sharp eyes surveying a battlefield of yucca, whose stalks shot skyward like swords. At one point, I’d begun counting and tallied a whopping six cars, one border collie and a dozen cows in the span of 40 miles.

No services, indeed.

I’d come to Chiricahua to hike and stargaze and gauge whether — in my inexpert opinion — the 12,000-acre monument with no restaurant, lodge or gas station and minimal cell service warranted an upgrade to national park status, a move under consideration in Congress. (Spoiler: I think it does!) What really sold me, however, was the chance to see a coatimundi (picture a long-nosed, arboreal raccoon) and to reclaim my camping mojo. I wanted to test the limits of my healing body and prove to myself that a few nights in the wild wouldn’t kill me. Andrea, the first friend I made when I moved to Virginia a dozen years ago, had simpler motives: She had vacation time to burn and knew I was in the market for a travel buddy. Luckily for me, Andrea shares my affinity for public lands and is as easygoing as they come.

Chiricahua National Monument encompasses the northern extent of the eponymous mountains in southeastern Arizona. The Chiricahuas, along with other ranges in this part of the world, are considered sky islands. These biodiverse havens — from the Sierra El Tigre in northern Mexico to the Animas Mountains in the bootheel of New Mexico — rise like islands out of an ocean of scrubland, their canyons, hillsides and summits providing a variety of habitats unavailable on the valley floor. With their jumble of ecosystems, sky islands meet the needs of a rich and remarkable assortment of montane- and desert-dwelling species. In the Chiricahuas, for example, you can find ring-tailed coatis alongside hoglike javelina, petite Coues deer sidestepping prickly pear, Mexican chickadees flitting over cinnamon-barked manzanita, and Douglas fir tucked up beside Apache pine.

After registering the “no services” sign and cruising past the unstaffed entrance station, we continued to the monument’s visitor center, arriving two minutes before closing. I snagged a map and, unable to help myself, asked the white-haired volunteer at the front desk about the best place to find coatis. She said that they often appear near the visitor center around that time of day, so we scrambled outside and struck out for some quick reconnaissance on the nearest trail. I’d skimmed my hand across the chunky bark of an alligator juniper and skipped over piles of scat before the reality of our surroundings sunk in. Gone was the sun-flayed valley. In its place was a pine-scented forest cloaked in shade. “It’s so quiet,” I whispered.

A Thorny Question

Why some saguaros grow more arms than others — and why it matters.

See more ›That evening, having failed in our cute-critter quest, we pitched our tent beneath a listing oak at the park’s lone campground. Like much of Chiricahua, the campground — with its 25 sites — feels intimate rather than sprawling. I’d reserved our spot knowing it was nestled alongside Bonita Creek, forgetting that the streambed would be dry this time of year. Rather than the soothing sounds of a brook, our site’s soundtrack consisted mostly of the ping and plink of falling acorns.

After we added boiling water to our dehydrated meals, Andrea scurried to her suitcase. She returned with a stuffed blue bear, plopping it beside our stove. I looked at my friend and raised my eyebrows in question. Turns out, her 8-year-old had insisted she pack said bear because it would, magically, improve the flavor of our camp food.

Night fell quickly, accompanied by a welcome chill and a handful of swooping bats. Donning our headlamps, we walked to the main road for a glimpse of unobstructed sky. Andrea, a self-professed space nerd, was particularly excited about the monument’s status as an international dark-sky park. “I love this,” she said, as she peered through her binoculars. We’d hoped to observe the Orionids, meteoric dust from Halley’s comet, but the evening was too young, the moon too bright. We examined a few lunar craters, located the star Vega and then shuffled back to camp.

The view west from Inspiration Point with Sulphur Springs Valley in the distance. Tens of thousands of sandhill cranes overwinter in this valley before returning to their northern nesting territories each spring.

©ALAN ENGLISH CPAThe elegant trogon is typically found in tropical forests, but four mountain ranges in Arizona, including the Chiricahuas, offer breeding habitat for this jewel-toned bird.

©FRANCIS MORGANView from Massai Point. According to 18th-century writings from Jesuit Juan Nentvig, Chiricahua is an Opata word for “wild turkey.” Though the birds were historically prevalent in the area, they had been extirpated by the mid-1900s. Beginning in 2003, the Arizona Game and Fish Department and the National Wild Turkey Federation collaborated to reintroduce the Gould’s wild turkey (one of two species native to the state) to mountain ranges in southeast Arizona, including the Chiricahuas.

©E.J. PEIKERCochise Head can be seen from the fire lookout on top of Sugarloaf Mountain.

NPCA/K. DEGROFFThe next day, after shaking off our stiffness, we set out for one of the National Park System’s last maintained fire lookouts, perched atop the 7,300-foot summit of Sugarloaf Mountain. The road to the trailhead ascended past lichen-smeared pinnacles before turning sharply. “Oh, wow!” Andrea gasped. The canyon had disappeared, replaced by a world of cascading ridgelines that stretched east into New Mexico.

After parking, we commenced the hike, tracing outcrops of chalky tuff before dipping through a tunnel. Andrea snapped pictures of the trailside foliage, as both of us struggled to identify the dainty flowers of one plant, the silvery leaves of another. By the time we’d worked our way around the Sugarloaf knob, our focus shifted, lifting to take in the expanse. Peachy pillars, anointed by sunlight, marched up the opposite ridge. We’d found what the Chiricahua Apache, who explored and moved through the region for centuries, called a land of “standing up rocks.” (A nomadic people living in scattered family groups, the Chiricahua left little evidence of their presence in the area aside from sparse circles of rocks indicating the one-time presence of shelters known as wickiups.)

A series of volcanic eruptions 27 million years ago spewed superheated gas, rock and ash across 1,200 square miles, blanketing the Chiricahua landscape in a debris layer some 1,600 feet thick. As the material cooled, it formed a rock called rhyolite. Then, at a rate of two-thirds of an inch per millennium, wind and rain, freeze and thaw cycles ate away at the rock, chiseling, carving and smoothing the expanse into a dizzying array of hoodoos.

On various hikes over the next few days, Andrea and I would marvel at these pyroclastic formations. We walked through valleys of cantilevered stone and beside slabs stacked like the cairns of giants. We spied one that looked like the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man and scores that could have been victims of Medusa. Walking alone up Lower Rhyolite Canyon on my last day in the park, I found myself in an amphitheater of these stony spectators. The feeling could have been eerie, but it wasn’t. I found comfort in the silence of their sentry, as if they possessed the wisdom of the ages.

Back at Sugarloaf, we pulled ourselves from the panorama long enough to reach the 1930s fire lookout. A squat building — half glass, half stone — it exudes a certain stoic melancholy. I peeked in at the deep enamel sink and the rust-red hand pump before pivoting for the 360-degree views. The peak known as Cochise Head in honor of the Chiricahua leader lies to the northeast. (It does, indeed, resemble a person’s profile, complete with an evergreen eyelash.) The volcano’s shriveled remnants are just visible to the south. And to the northwest, Sulphur Springs Valley unfurls for some 40 miles before butting up against the tiny town of Willcox. We could have lingered longer, but we were late for a date with some birds.

I have to admit, birding’s not my thing. But it is a thing at Chiricahua, where more than 200 species have been cataloged. And so, armed with my husband’s binoculars and Andrea’s checklist, we descended from one of the highest points in the park to the grasslands at Faraway Ranch for a ranger-led walk. I had passing success pinpointing the chubby ruby-crowned kinglet and dusty gray canyon towhee based on the group’s excited exclamations. But soon all the squinting and zooming lost their appeal, and I found myself falling behind, more enchanted by a historic windmill and a peculiar fireplace along the back wall of a pale pink home. I was contemplating the chimney stones, trying to decipher the dates and names engraved on each, when a wiry woman I initially mistook for a birder approached.

Lillian Riggs, known as “the lady boss of Faraway Ranch,” in a photo circa 1919. She continued to oversee ranch operations for nearly 30 years after her husband died in 1950. What little of the homestead hadn’t been sold to the Park Service during her lifetime passed to the park two years after her death, safeguarding this window into frontier history.

NPSJoAnn Blalack has been the resource manager for a trio of southeast Arizona parks, including Chiricahua, for four years. She’d seen our bevy of birders while on her morning walk and decided to tag along. Noticing my interest in the fireplace, Blalack explained how the blocks had been hewn and engraved by buffalo soldiers of the 10th Cavalry Unit, one of four all-Black regiments created after the Civil War. The men were stationed in the vicinity of Bonita Canyon during the final years of the Apache Wars, when the U.S. government — intent on opening the area to ranchers — engaged in a tragic and bloody decadeslong offensive that culminated in the Chiricahua Apache’s removal. (Read more in the sidebar.) Before moving north to Fort Verde, the soldiers erected a monument to President James Garfield, the theory goes, because he supported equal pay for Black and white troops. When no federal funds arrived for the structure’s upkeep, Lillian and Ed Riggs — then owners of the land — used the stones to craft a fireplace for their ranch house as a last-ditch, if questionable, effort at preservation.

After admitting she’s not holding her breath for a national park designation (“they’ve been talking about that since I got here”), Blalack peeled off, leaving me to catch up with the group. We passed through an orchard, rife with aging persimmon trees, and by the remains of a cabin once owned by the Riggses’ neighbors. While a few settlers made their homes here at the turn of the 19th century, it was the Riggses, and Lillian’s mother, Emma Erickson, who arguably left the biggest mark.

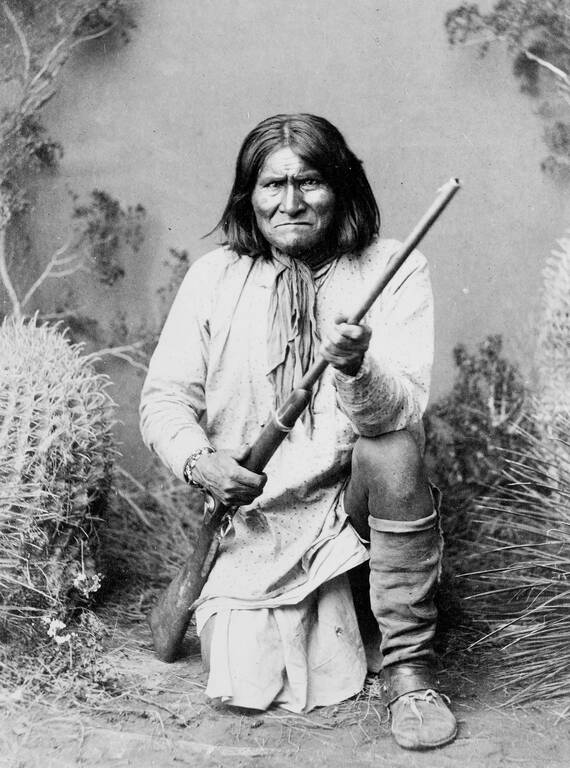

Geronimo, a fearless leader of the Chiricahua Apache, evaded Mexican and American forces for more than a decade before formally surrendering in 1886.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESSIn 1886, the same year the Chiricahua leader Geronimo surrendered and the Apache Wars ended, Emma, a 32-year-old Swedish immigrant, purchased a two-room cabin. (This building would evolve over time, morphing into the pink homestead I’d admired earlier.) “She found the place and thought it the most gorgeous spot she had ever seen,” wrote her husband Nels Erickson in Hoofs and Horns magazine. “Large oak trees lined the canyon, grass was three feet high wherever she walked, and Bonita Creek was then running like a full sized river.”

Emma would work this land for most of her life, raising a family and running the ranch. Nels (also known as Neil) helped when home, but it was 15 years before he found a nearby job, meaning he was often gone for months on end. Lillian followed in her mother’s footsteps and took over the family business, which eventually grew to include a guest ranch. She and Ed became leading advocates for the creation of the monument, offering horseback tours through what was billed then, as now, as a “wonderland of rocks.” Their passion paid dividends when President Calvin Coolidge established Chiricahua National Monument in 1924.

As Andrea ticked off birds she’d spotted, from the Say’s phoebe to the Arizona woodpecker, I snapped a final photo of the ranch’s weather-beaten barn and headed to our rental car. We had one more hike to go.

Desert Storm

Fort Bowie stood at the center of America’s most brutal Indian Wars.

See more ›This one, a succession of connecting trails, traversed the core of the monument. We’d hoped to complete the Heart of Rocks Loop but found, a couple of hours in, that our eyes were bigger than our legs. We’d both packed enough water, but neither of us had our headlamps (rookie mistake), and I was worried about waning daylight, flagging endurance and the raw patch along my spine courtesy of my chafing backpack. So, we plunked down on a fallen tree to consult the map. We opted to cut our hike short after detouring out to the aptly named Inspiration Point where we stumbled across a metal container emblazoned with the words “open me.” Popping the top, I leafed through a quirky mix of messages and images, wet wipes and candy wrappers. I got sidetracked reading a note about someone’s first kiss and missed the lewder content that had Andrea averting her eyes. We closed the box. After a selfie in front of the spiry view, we about-faced and hiked out the way we came.

That night, we returned to our campsite and were immediately greeted by our neighbor: a wriggling, 6-month-old pup named Bluetooth. All around us, the campground flared to life in the peaceful gloaming. The patter of baseball game announcers filtered out from an RV. Savory smells wafted from grills. A Mexican jay hopped close, cocking its head as if begging for a handout. An owl hooted. More acorns fell. While we sat hunched over our meal pouches, Sanober Mirza, a colleague from Tucson who had serendipitously picked the same weekend to go camping, sauntered up. “Did you see coatis?” they asked. I shook my head, so Sanober whipped out a phone and pressed play. I sat, amazed, as I watched a band of maybe 30 coatimundis tumble across the screen. Sanober had encountered the racoon relatives just that afternoon. The cuteness was off the charts.

SIDE TRIP: FORT BOWIE

In the small hours of the morning, I crawled out of the tent to watch another day unfold. I hugged my knees and craned my neck. Just before the stars vanished into a whitewashed dawn, a meteor slashed across Orion’s Belt.

I had another day to explore the park, but Andrea needed to get home for a meeting. So, after rolling and stowing her belongings, we drove to the Natural Bridge trailhead for a pre-airport jaunt. Breaking into an arena of agave and stone, Andrea paused to set up a coffee station on a flat rock. As she sipped, sunlight and silence settled around us, wrapping us each in our thoughts.

On the way back to the car, I asked my friend if anything had surprised her about Chiricahua. After considering her response, she said something about how the monument felt approachable, going so far as to call it “cozy.” That seemed an odd way to describe a park, but the more I thought about it, the more the word fit. Chiricahua is just large enough that you can have an adventure and see some beautiful and surprising things, but not so big as to overwhelm. It may require time — and intention — to get here, but once you arrive, it doesn’t take hours to drive from one end of the park to the other. There is, in fact, just one park road and only a handful of parking lots. And while there are only about 15 trails, many of them connect, turning every outing into a pleasing series of fork-in-the-road questions: Do I turn left and return to my car, or do I go right for an additional 3, 6 or 12 miles?

All of this creates a sense of community among the monument’s visitors, which numbered around 60,000 in 2022. I’ve never been to a park and encountered the same people over and over, but on this trip, Andrea and I did. Fellow birders turned out to be campground neighbors. Sanober and I ran into each other outside the campground restroom and again on Ed Riggs Trail. Even the strangers we passed while hiking the crowd-free paths were unusually amiable. When I offhandedly said “Roll Tide” to a guy in an Alabama shirt, he paused to chat. “People might wonder why I’m not watching the game,” he said. He shrugged, lifting his hiking pole: “I’d rather be out here doing this.”

The things that make Chiricahua so charming, however, also raise questions about its ability to handle an influx of visitors if it becomes the 64th national park. This year marks the monument’s centennial, and momentum seems to be building for a new designation. Those who hope Chiricahua joins the sisterhood of national parks see a status change as affirmation of the monument’s worthiness. Others wonder if a new title would attract hordes of motorists and hikers, simultaneously harming a landscape that consists primarily of designated wilderness and detracting from the visitor experience. During Saturday night’s campground program, someone asked how the park site would manage a surge in popularity. “That is the 6-million-dollar question,” said Suzanne Moody, a ranger who’s served Chiricahua for 29 years. “Enjoy the peace and quiet while you can.”

After dropping Andrea at the airport, I returned to the park just in time to see a roadrunner and a coyote cross the road — a cartoon come to life. Then, with the ranger’s warning ringing in my ears, I headed out for one final hike to soak in Chiricahua. I lengthened my stride as the sun rose, bathing the rock formations in a honeyed glow. The path curved, and I tripped, coming perilously near the edge. I found myself reflecting on this crazy, fragile, no-guarantees world, where one moment you’re cruising along, invincible, and the next a careless step or an invasion of bacteria forces you to confront your mortality. Before turning around to start my long journey home, I slowed my breathing — in, out, in — each breath a meditation in gratitude. I had crossed the “no services” Rubicon, and I had survived.

I never did see a coati. But you know what? That’s OK. I’ll just have to come back.

About the author

-

Katherine DeGroff Associate and Online Editor

Katherine DeGroff Associate and Online EditorKatherine is the associate editor of National Parks magazine. Before joining NPCA, Katherine monitored easements at land trusts in Virginia and New Mexico, encouraged bear-aware behavior at Grand Teton National Park, and served as a naturalist for a small environmental education organization in the heart of the Colorado Rockies.