Fall 2020

Call of Duty

For nearly 50 years, Lt. Col. Cheeseman and his troops have been a mainstay at Dry Tortugas National Park in Florida, where they have fixed up everything from a rusted iron lighthouse to leaky toilets.

Retired Lt. Col. Jerry Cheeseman held one hand over his brow to shield his eyes from the afternoon sun while he surveyed his men. They were some 50 feet below, replacing a shed over a fuel storage tank on a small patch of cement. From this windswept perch atop Fort Jefferson, they looked miniature. Behind them, the endless ocean rolled toward the horizon.

It was day five of a nine-day work mission, and so far, Cheeseman was pleased. The younger, active reserve members of his squadron had already departed for the mainland, after completing the repair and installation of air conditioners in the living quarters for the park’s personnel. Now it was up to Cheeseman and his older cohort — mostly 50- and 60-somethings — to finish building the shed.

“I’m getting too old for this,” said Cheeseman jokingly — not for the first or the last time that day — as he descended the steep spiral stairs from his vantage point.

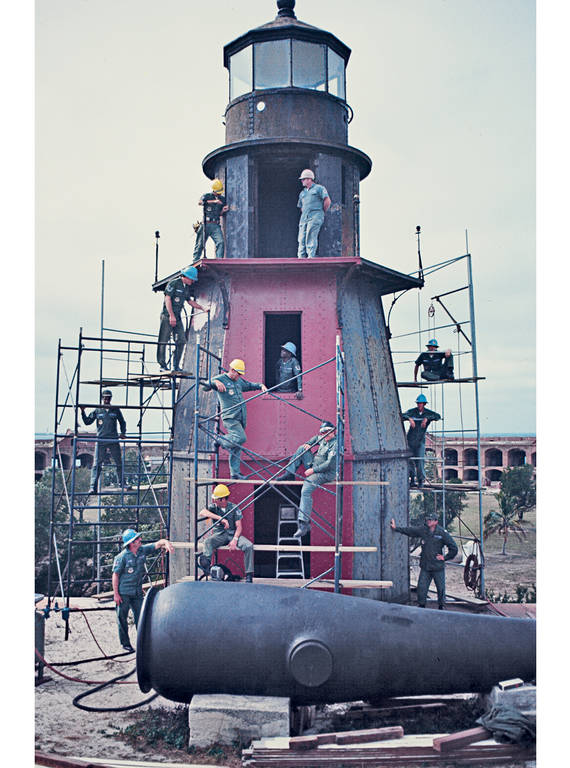

Cheeseman and a rotating crew of men and women of the 482nd Civil Engineering Squadron have volunteered at Fort Jefferson most years since 1972. A mix of active and retired Air Force reservists, they have had a hand in building and rebuilding nearly every modern amenity there. With each major task typed out as a line item, the list of their accomplishments is 10 pages long. Some of their feats: constructing cannon platforms; installing a garbage incinerator and desalinization systems; restoring a lighthouse; setting up interpretive tour displays; building employee living quarters and campground latrines; and refurbishing and expanding a museum.

Volunteers restore the iron lighthouse at Dry Tortugas in February 1976.

U.S. AIR FORCEThe centerpiece of Dry Tortugas National Park, Fort Jefferson was designed to control the trade route between the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. Built over a 30-year period starting in the mid-1800s on a sweltering island with no source of freshwater, the fort is a 16-acre, roughly 16 million-brick testament to sheer will. Dry Tortugas is located about 70 miles from Key West, and even with the help of today’s technology, maintaining the park is a challenge. Freshwater availability is still very limited, as are housing and generator power, which severely restricts the work that can be done. Everything must be transported by boat or seaplane, so deliveries are expensive and can be held up by stormy weather. This makes the efforts of Cheeseman and the 482nd invaluable, especially at a time when national park budgets are shrinking and the maintenance backlog across the National Park System has reached almost $12 billion.

“The 482nd works closely with park staff to identify and complete projects that make the park a richer and more pleasant experience for park visitors,” said Jacqueline Crucet, associate director of national partnerships for NPCA, who helped bring in younger veterans to work with the 482nd at the park. “They are just so respectful of people and so dedicated to their work at Dry Tortugas. The colonel and his crew have done a great deal for this park.”

But it’s not a one-way street. At Fort Jefferson, the reservists can hone their plumbing, electrical, construction, engineering and management skills, which helps them prepare for deployment.During Operation Desert Storm in 1991, the Air Force called for 50 volunteers from the 482nd and immediately filled those slots. The reservists’ readiness was a point of pride for Cheeseman.

“The mission of the reserves is to be trained and ready for deployment around the world,” Cheeseman said. “This is good systems skills training for our active members of the squadron, and the park likes the free labor. One piece of government helping another. It’s a win-win.”

NPCA AT WORK

Cheeseman’s own military career spanned 28 years, during which time he served in the Air Force both on active duty and as a reservist. Before retiring in 1992, he was a squadron commander during Desert Storm in Saudi Arabia, where he and his troops deconstructed a temporary base used for aircraft missions. He now runs a South Florida construction management company — essentially a one-man operation — and volunteers as an advisor to the local Little League.

While Cheeseman is a fixture here, the other volunteers from the 482nd can vary from year to year. These days, most are retired, though active-duty reservists often leave their civilian jobs for a few days to come help, especially with the more labor-intensive projects. One such job was the construction of the concrete platforms on which the fort’s iconic cannons sit.

“This is one of our better claims to fame,” Cheeseman said, pointing to a cannon about the size of a box truck. “Up until the ‘80s, the cannons were just lying in the sand. For years, they rusted in front of our eyes.”

Had the fort been fully outfitted as originally designed, it would have held 450 cannons, some of which could shoot iron shells 3 miles into the ocean. Most of the fort’s cannons were sold for scrap in the early 1900s, but a few that were perched at the top of the fort with no easy way to lower them were left alone by scavengers. Today, Fort Jefferson houses six of the world’s 25 known remaining Rodman cannons of this size and four smaller Parrott guns.

In 1982, the 482nd lifted one of the Rodmans onto blocks to hinder further deterioration. (Others followed in subsequent years.) Then in 2008, Nancy Russell, who was the museum curator for Dry Tortugas and who spearheaded the cannon conservation and mounting project, approached Cheeseman to see if he’d be interested in building a platform to hold an 11-ton swivel carriage and a 25-ton Rodman gun. No crane could be brought on the island, and no hauling equipment could be anchored on the fort itself, so lifting the building materials and tools made for a particularly interesting puzzle. Cheeseman jumped at the opportunity. With a lot of sweat and the help of a block-and-tackle pulley system, he and 17 reservists hauled the supplies to the top of the wall and built a replica of the original platform, using concrete with a wood texture. The first platform was completed in 2010, and they built smaller platforms for the other five Rodmans over the next couple of years.

“Seeing the cannon above the fort’s wall as visitors approach by boat gives them a better sense of how vulnerable an approaching ship would have been to the fort’s armament,” Russell said. “Seeing the mounted guns up close inside the fort helps visitors understand the scale and complexity of that technology.”

Working there has also helped some of those volunteers smooth a rocky transition back to civilian life. Marine Gunnery Sgt. Eddy Angueira tagged along on this trip at the suggestion of a therapist from the Department of Veterans Affairs. After serving in combat operations in Iraq, Angueira, 47, developed post-traumatic stress disorder, which eventually led to early retirement and depression. “I pretty much stayed locked up at home,” he said.

But thanks to projects like this, he’s been able to gain back a sense of belonging and connection that is helping him heal. “I feel very proud that I was able to contribute a small part to maintaining the restoration of an important landmark of American history,” he said. “I want my kids to experience this.”

Sharing park experiences has also created strong bonds among members of the 482nd, even when the project is as unglamorous as this year’s new fuel shed. Painting together, it took the team of retirees less than an hour to cover the entire structure. With the shed construction zipping along ahead of schedule, the mess hall at lunchtime on day five was filled with laughter and general cheeriness. Conversations wandered from the inhumanity of eating an entree of brats with no beer to wisecracks about “old guys.”

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›One after another, the reservists said that Cheeseman is what keeps them coming back to Dry Tortugas. “The draw is him. He’s our commander,” said retired Senior Master Sgt. Joseph Cieslinski. Out of earshot, Cheeseman demurred. “All I do is get these men here,” he said. “They’re the ones that do all of the work.”

Cheeseman said he returns year after year for many reasons. He loves the camaraderie, exercise and beautiful landscape. As a civil engineer, he marvels at the fort’s architecture and relishes the chance to help preserve it. And most of all, he enjoys training younger generations of reservists.

Cheeseman (who wouldn’t disclose his age despite repeated inquiries) has white hair and is well into retirement, but he intends to keep leading troops as long as he can. “I feel like I’m 57,” he said.

About the author

-

Karuna Eberl Contributor

Karuna Eberl ContributorKaruna Eberl writes about wildlife, history and adventure from the sandbars of the Florida Keys and the high country of Colorado.