Fall 2017

Esther of the Rockies

She left the corporate world to homestead in the mountains and became the Park Service’s first female nature guide.

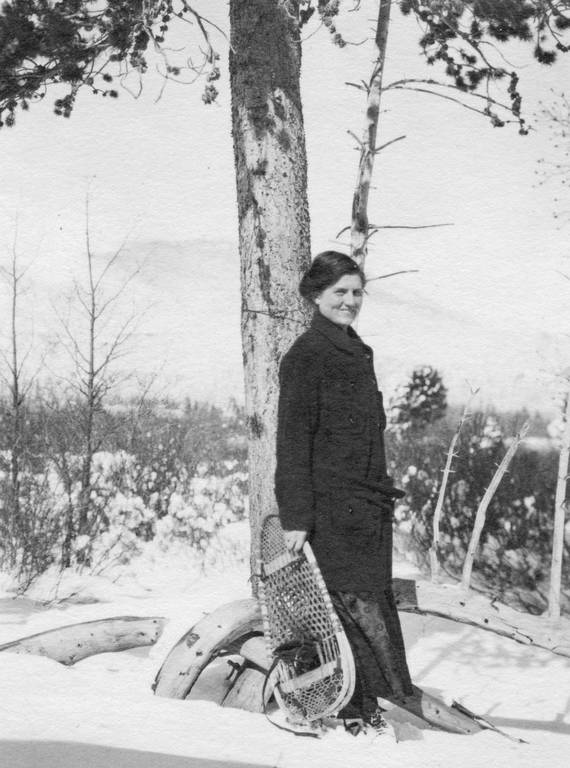

On Christmas morning, 1916, Esther Burnell put on her snowshoes, left her cabin high in the Rockies and trudged through the snow for 8 miles. By her friend Katherine Garetson’s account, it was the “dreariest winter ever known in the mountains.”

Weeks earlier, Esther and Katherine, both homesteaders, had decided to celebrate the holiday with a picnic by a little stream halfway between their respective claims, near what is now Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado. They hadn’t heard from each other since hatching the plan, so each feared the other had chickened out. After hours of effort, they bumped into each other.

“I didn’t think you would come!” they rejoiced before enjoying a Christmas dinner of canned tomato soup, bacon sandwiches and coffee under falling snow. When Esther had arrived in the area a few months before, Katherine — by then a seasoned homesteader — initially dismissed the newcomer as a frail city slicker. Now, sitting by the blazing fire, 27-year-old Esther was the picture of health and vigor. “She looked wonderfully pretty, animation transforming her into a beauty,” Katherine later wrote.

Esther Burnell cemented her reputation as an intrepid mountaineer when she snowshoed for 30 miles to meet friends on the other side of the Continental Divide.

REPRINTED BY PERMISSION OF ENOS MILLS CABIN COLLECTIONKatherine was not the only local impressed by Esther’s metamorphosis. A disciple of famed conservationist John Muir, Enos Mills, whose lifelong dream to create Rocky Mountain National Park had recently been fulfilled, took notice, too. But it wasn’t only Esther’s snowshoeing skills that wowed him. In her, he found a kindred spirit who used all her senses to appreciate the natural world and who thought there was no better teacher of nature than nature itself. And so Enos, who was running a nature school at the inn he operated on the trail to Longs Peak, offered to train Esther as a guide.

Esther’s older sister Elizabeth joined her for the training, and in the summer of 1917 — one year before the National Park Service hired its first two women park rangers — the sisters became the first female certified nature guides in the National Park System.

Esther was born in Kansas, and she attended Lake Erie College near Cleveland before studying interior design at the Pratt Institute in New York. She went on to become an interior designer for the Sherwin-Williams Company but felt burnt out after years of hard work. Seeking a break, she decided to spend the summer in Estes Park, a town just outside the border of the new national park. Her sister joined her, but returned to her teaching job in California at the end of the season. Esther stayed.

THE FIRST HOMESTEADER?

She did some secretarial work for Enos, typing drafts of his book, “Your National Parks,” but spent much of her time exploring the nearby mountains by day and night. “It was a great area for women to get out and get some freedom, frankly,” said Eryn Mills, Esther’s great-granddaughter, in a phone interview.

It didn’t take long for Esther to resolve to trade her interior design career for a life in the mountains. “Here is a woman homesteader who comes from a very comfortable life,” said Kurtis Kelly, a storyteller and reenactor who has performed at Rocky Mountain. “And she decides to leave all of that behind and go build a little cabin.”

Esther picked a spot 4 miles west of Estes Park. A meadow framed by a granite cliff and a forest of pines, firs and aspens offered just enough space for a small garden. On the train to Denver to file her claim, which would give her the right to the land as long as she farmed it for five years, Esther met Enos, who was on his way to St. Louis. He gave her a hint of his developing feelings for her: “Not leaving the country, I hope!”

Esther had no such intention. She drew the plans for her cabin and helped build it, and she made her own furniture. Rumor had it that she “shingled as fast as a man.” She named her cabin “Keewaydin,” a Native American word for “northwest winds.”

Esther prospered in her new life, often surprising locals with her derring-do. When advised to wait until daylight to return to her cabin because of roaming bears, Esther replied: “Well, I’ll certainly start at once. I have been wishing I might see a bear.” A 30-mile snowshoe walk across the Continental Divide to meet with friends cemented her reputation as an intrepid mountaineer.

Meanwhile, Enos was campaigning for the certification of women guides. “He found that women tried harder,” Eryn said. Rocky Mountain’s superintendent was initially reluctant, but he eventually relented, acknowledging later that women guides filled a “long-felt want.” Park officials didn’t allow women to guide above the timberline unless accompanied by a male guide, but after she officially became certified, Elizabeth repeatedly violated this rule, routinely taking groups to the summit of 14,259-foot Longs Peak.

Esther was a natural at guiding, Eryn said, but her career was derailed by the very man who trained her. Enos would stop unannounced by her cabin on his horse, Cricket, and he contrived to get Esther to attend a lecture he gave about a romance between two goldfinches. During the lecture, he made frequent eye contact with Esther and rushed to her side afterward. “It was a very veiled kind of romantic plea to her,“ said Jim Pickering, a local historian.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›It worked. Enos and Esther were married in August 1918 at an intimate ceremony at his cabin — now a museum run by Eryn and her family. In the spring of 1919, their daughter Enda was born, and Esther became a nature guide to Enda, helping her identify flowers and follow coyote tracks in the snow.

Just three years after Enda’s birth, Enos died at the age of 52. But Esther didn’t indulge in self-pity. Besides raising Enda alone, she ran Enos’ Longs Peak Inn, published several of his books and took on his fight over access to Rocky Mountain. She died in Denver in 1964.

A few years ago, Eryn met an elderly woman who had worked for Esther at the inn in the 1940s. Eryn took her aside and asked her about her great-grandmother. “She gave me this intense look,” Eryn recounted, “and she said: ‘She was formidable.’”

About the author

-

Nicolas Brulliard Senior Editor

Nicolas Brulliard Senior EditorNicolas is a journalist and former geologist who joined NPCA in November 2015. He writes and edits online content for NPCA and serves as senior editor of National Parks magazine.