Spring 2017

Reflections on a Man in his Wilderness

Remembering Richard Proenneke.

In 1968, Richard Proenneke — a 52-year-old Iowan who’d fallen in love with the Alaska outback — headed to a remote spot in the southwestern part of the state to test himself. Using simple handheld tools, many of which he’d fashioned himself, he constructed a log cabin on the edge of Upper Twin Lake and went on to live in his expertly crafted home, alone, for the next 30 years. His quiet life and wilderness ethic — the belief that wildlife should not suffer for his presence — could easily have gone unnoticed, but his story became widely known in 1973, when Sam Keith published the book “One Man’s Wilderness: An Alaskan Odyssey,” based on Proenneke’s daily journal entries and photographs. Eventually, large swaths of the diaries, more than 250 steno pads in all, were published in three edited volumes, and several filmmakers used footage Proenneke had shot in biographical movies.

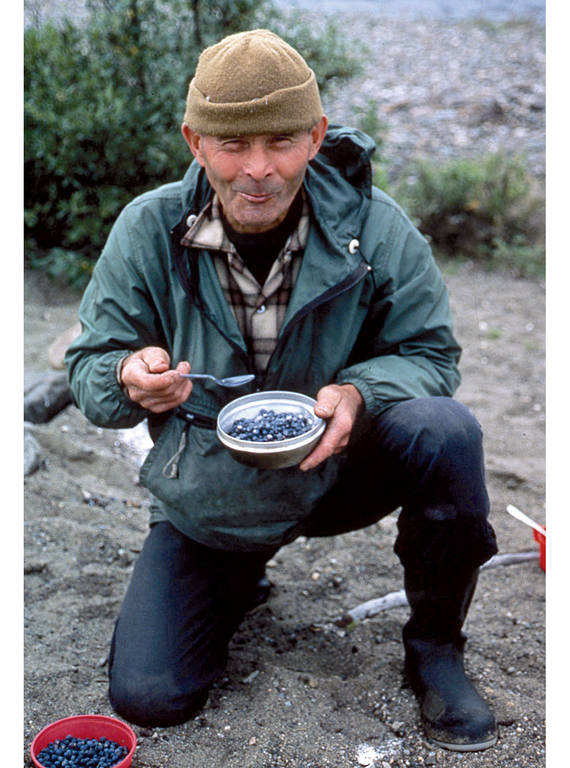

Eating fresh blueberries in a spot along the Chilikadrotna River.

© MAGGIE YURICKTo read “One Man’s Wilderness” is to be swept into a slower, simpler world. Fans of the book (and the other publications and films) admire Proenneke’s self-sufficiency, close observations of nature and unencumbered, off-the-grid lifestyle. He wrote: “I have found that some of the simplest things have given me the most pleasure. They didn’t cost me a lot of money either. They just worked on my senses. Did you ever pick very large blueberries after a summer rain? Walk through a grove of cottonwoods, open like a park, and see the blue sky beyond the shimmering gold of the leaves? Pull on dry woolen socks after you’ve peeled off the wet ones? Come in out of the subzero and shiver yourself warm in front of a wood fire? The world is full of such things.”

Proenneke left Twin Lakes in 1998, when he was 82, to move in with his brother in California. He donated his log cabin and most of his possessions to the National Park Service, which had managed the area since 1978, when it became part of Lake Clark National Monument. (He never had valid title to the land, but some park administrators consider the cabin a gift nonetheless.)

Proenneke died in 2003, but his journals continue to find new audiences, and every year, visitors make the long journey to the Richard Proenneke Site to see his carefully preserved home in what is now Lake Clark National Park and Preserve.

Alan and Laurel Bennett knew Proenneke from their time working at Lake Clark, and after they retired, they served as volunteer guides at his cabin for six years. During those summers, from 2008 to 2014, they found that many visitors asked them a variation of the same question: “What was Dick really like?” It actually wasn’t all that hard to answer: Although he lived by himself, Proenneke interacted with many people — pilots, hunters, fishermen, neighbors, park rangers — and as his legendary status grew, more and more visitors traveled to the far reaches of the park to meet him. Everyone, it seemed, had a story about him, and the Bennetts decided to collect some of them before it was too late. In October, the couple published “Dick Proenneke: Reflections on a Man in His Wilderness,” a compilation of essays written by (or drawn from interviews with) his friends and admirers.

Proenneke would have turned 100 last year; we are pleased to mark the anniversary by publishing some remembrances adapted from the book.

—Editors

A CUP OF TEA

I first met Dick in the summer of 1979. I was one of 19 rangers from the Lower 48 who had been selected and sent to Alaska to watch over the new Park Service monuments covering 48 million acres that had been designated by President Jimmy Carter. I was the first and only field ranger assigned to Lake Clark National Monument that year.

That summer, during my patrols, I flew over and landed at Twin Lakes a number of times. I was not sure it was true, but I had been told that if Dick liked and accepted you, he would invite you for a cup of tea. My first meetings with Dick were a bit formal because of a certain amount of posturing by both of us. I am sure Dick was probably wondering just what was in store for him and his cabin with the new national monument. But on the third visit, he invited me to have a cup of tea, and the courtesy was extended every visit thereafter. I think we both recognized we were on the same side concerning the protection and preservation of the wildlife and natural resources in the new park site.

Dick always left a map of the area on the cabin table and a flagged pin to show exactly where he intended to go that day. To my knowledge, the cabin door was never locked. I asked him why he placed the pin on the map and he jokingly responded, “So if anyone is interested enough, they would know where to look for my body!” On a more serious note, visitors who had business with him could see where he was and perhaps, how long he might be gone. The map was so full of holes from past pin placement that it looked like one of those old-time punchboards.

I remarked one time about how clean his cabin’s gravel floor was. He said, “Well, you arrived just after spring cleaning.” “How so?” I asked. Dick explained that he scooped up the gravel from the floor one bucket at a time, took the bucket to the lake shore, washed the gravel, then spread it back on the floor of the cabin.

He followed the practice of waste-not-want-not. Once when we visited, I noticed a fish line in the lake with what appeared to be fish intestines carefully threaded on the hook. I asked him why he was using intestines for bait. He said that he had caught a lake trout that morning and rather than throw away the insides, he put them on a hook and figured he would catch a burbot for another meal.

After I left Lake Clark at the end of the summer, I made up a large package of assorted teas and sent him a surprise bundle with a thank-you note for helping to educate this park ranger. I considered it an honor to have met and spent some time with this remarkable man.

Stu Coleman recently retired from a job working among the bison and bears at Yellowstone National Park.

VISITING THE SEAMSTRESS

One afternoon, the inseam of Dick’s pants tore from his foot clear up to his crotch. His pants were just flapping in the wind where the seam used to be. He and Will Troyer, a park wildlife biologist, were in the middle of a caribou calf count at Turquoise Lake. The wind was getting stronger, and the noise of Dick’s flapping trousers was getting louder. Finally, Will asked, “What are you going to do?”

Dick replied, “Oh, I’m going to go visit a seamstress.” He handed his clipboard to Will, turned toward the lake and took off. An hour passed, and Will looked up to see Dick coming back with his pants neatly sewed up. Astonished, Will asked, “Well … how did you do that?”

Dick explained that he’d gone down to the creeks at the head of Turquoise Lake. He knew that sport fishermen used that area during the summer and invariably somebody got a snag in their line, so they would just cut the line off and throw it on the beach or in the bushes. He searched the area and soon found some monofilament fishing line and a discarded beer can. Next, he used his knife to cut a narrow wedge-shaped piece of metal out of that beer can, and he rolled it up tight in the shape of a needle. Finally, he used his knife to drill a hole in the wider end of the needle. Then it was a simple matter of threading the needle with the line and getting on with the business of sewing his pants.

A week or so before Dick’s 80th birthday, I flew up to deliver his mail. As I nosed the floats onto his beach, Dick came down, and I asked if he had any plans for his birthday. He said, “I’ve been practicing chin-ups so that on my birthday, I can do 80.”

He was up to 60 when I landed, and he said he was adding two to four a day. Sadly, I missed his birthday, but I did get up to see him a week later. First thing I asked him was, “Did you do those 80 chin-ups?”

“Oh, I felt good that morning,” Dick said. “I got up and did those 80 chin-ups.” Then he paused. “I felt so good,” he continued, “I just went ahead and did 100.”

When he was still a teenager, Glen Alsworth Sr. began flying to Proenneke’s cabin to deliver his mail. He went on to become a well-known Alaskan pilot and the mayor of the Lake and Peninsula Borough.

THE FISH KNEW WE WERE HAVING A PARTY

I think of Dick as a kindred spirit. I grew up here in Alaska. My backyard was a mountain, my front yard was a river and my best friends were the trails. Dick loved those things as much as anybody I’d ever met.

Canoeing with Dick was easy. We paddled at a steady but slow pace. Being together was always very comfortable, whether conversation came or not.

Once, when we were canoeing, I asked him, “Do you get lonely, or is this enough?”

He said, “I never get lonely.”

But then he wrote me a letter afterward and said, “After you left, I felt lonely.”

One fall, I came to visit Dick over my birthday. It’s always a beautiful time of year there, and he made my birthday a very special day. We got ready to go on a long hike, but before we left, we did my favorite kind of fishing. He took some line and threw it in the lake with a hook, and then we headed up behind his cabin. Way back up.

At the upper end of the valley, Dick said, “See that glacier over there? That glacier doesn’t have a name. I’m going to name it Alison Glacier.” I don’t know if it’s official or not, but years later, I learned that the Park Service stuck that name on its map.

Proenneke wrote regularly in his journal; he filled hundreds of steno pads, many of which the Park Service now owns.

NPSWhen we got back to Dick’s cabin, we found a very large lake trout on the line, and Dick made much of it. He said, “Oh, the fish knew that we were having a party today.”

The day after my birthday, we went to the other side of the lake and picked blueberries. Those blueberries were the best ever. I’d love to go back just to pick blueberries.

Alison Woodings never returned to Twin Lakes, but she corresponded with Dick for many years. Before settling in the Matanuska-Susitna Valley where she grew up, she taught school in Tanana, Ketchikan and Fairbanks.

SMALL MOMENTS

I’ve never known a person who could put as many miles on his legs as easily as Dick. He commonly walked the legs off people half his age, even as he approached his 80th birthday. After one tiring hike up and over Low Pass to the Kijik area with my sister and Dick, who was then 79 years old, we returned to soak our feet in the lake in front of Dick’s cabin and eat his famous blueberries with Tang. After a moment, he asked, “Well, girls, where are we going to hike tomorrow?”

On my last visit to see Dick, in the late 1990s, he wanted to show some visitors the Teetering Rock above Hope Creek. By then, he was more frail but still able to make his way up the trail to his favorite rock. After a little while, it was clear the visitors from California wanted to keep moving, so they quickly left to make their way down the mountain and back to their boat. It occurred to me that they had just missed out on one of the most unique moments of their lives — to spend some quality time with Dick. If they had only slowed down to savor the moment. But they were still on California time, rushing about and trying to see and do everything they could.

I knew when I flew out that I might not see him again, and that turned out to be the case. We continued to exchange letters for a few more years, even as Dick’s health failed more and more. His letters are some of my most cherished possessions — words of wisdom from a man I loved and admired.

Although it’s been years since Dick’s passing, I still think of him whenever I see something unusual or interesting in the natural world. How I wish I could tell him about it in a letter and seek his thoughts.

Chris Degernes was Proenneke’s nearest neighbor at Twin Lakes for many years. Today she lives at Cooper Landing on the Kenai Peninsula.

CALL ME DICK

I met Dick Proenneke in 1982 when I was a seasonal park ranger on my first summer assignment in Alaska. My partner, Tim Wingate, and I would be flown to Twin Lakes for a variety of assignments. We’d always check in with Dick whenever we were up there. He was very welcoming and very friendly, and he helped us out with all kinds of things. I was always amazed at his cabin, cache and woodshed — how immaculate they were and the craftsmanship they exhibited.

One day I learned that Dick did have a sharp side to his personality. The early 1980s must have been an anxious time for Dick and many others who lived inside the boundaries of newly created parks and preserves. His cabin was illegal at the time, though of course we gave him five-year leases and ultimately a lifetime lease. But it’s understandable that back then, Dick was apprehensive whenever high-ranking park officials came to his cabin.

That year, two associate regional Park Service directors flew in to meet Dick. High-level park administrators, although well intentioned, can sometimes seem a bit arrogant. Maybe it rubs off on them during their stints in Washington, like spruce pollen on a moose.

I was at Dick’s place the day the associate directors visited. After they left, I asked Dick, “So how’d it go?” He instantly lit into them. He said, “Well, they got off that airplane, introduced themselves as director this and director that and then called me by my first name like we went to school together.”

It offended him that they wanted respect because of their lofty titles, yet they didn’t extend the same level of esteem to him. For me, this event was quite a good lesson in etiquette and the importance of treating everybody with utmost regard.

Tom Betts is currently superintendent of Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument.

THEY GOTTA WORK FOR IT

When I moved back north to Alaska in 1992 to work as the pilot for a fishing lodge, I’d frequently take guests to see Dick. We would just show up, and if he was there, Dick would give us a little tour of his place, explain his daily routine and pose for pictures. He loved the photo sessions and knew exactly where he wanted everyone to stand to take advantage of the sun. He always liked to have people get pictures of themselves looking out through the top of the Dutch door of his cabin. We still do that today.

“His birds” — gray jays — were always part of the visit. If the jays hadn’t already been drawn in by the sight and voices of lodge guests milling around the cabin, Dick would call them. “Hey, guys, come on, you guys.” Dick’s jay calling is etched in my memory. When they came in, he would pass out crackers and tell visitors, “Now hold the cracker tight. Don’t just give it to them.” He’d really make them peck and pry to pull it out of his hand. Some guests would be a little timid at the prospect of a screaming gray jay landing on them, and they would just place the cracker in the palm of their hands. “No, oh no,” Dick would quickly command. “You want to hold it tight. They gotta work for a living.”

Bush pilot and fishing guide John Erickson has been flying visitors to Twin Lakes for almost 25 years. Since 2012, he has worked for Operation Heal Our Patriots, flying wounded veterans in to see the Richard Proenneke Site.

BETTER FRIENDS

When I worked at Lake Clark in the summers of 1990 and 1991, Dick and I would check in with each other on the radio most mornings.

“Lower Lake, Upper Lake,” he’d say.

“Upper Lake, Lower Lake,” I’d respond.

“What are ya gonna do today?”

“Well, maybe take the Klepper kayak over to the other side and see if berries are ripe. What are you doing?”

“I’m cooking beans.”

“OK. Give you a berry update later.”

Dick never changed his clock for daylight savings time and thought it was dumb when Alaska merged all its time zones. So his clock was behind mine. If we checked in at 10 a.m., it was only 8 a.m. for him.

Dick had scores of fans from all over the U.S. and beyond. One of his admirers didn’t live too far away and, in fact, owned the small lodge that had been built in the only private non-native inholding in the Twin Lakes area. Chris Degernes made Dick chocolate peanut clusters a few times a year. Afraid he didn’t have the discipline to keep from eating the whole box at once, he stored them in an abandoned cabin he used as storage. Once in a while, on a visit, we would walk down and each get two — one for eating right now and one to take back. His smile was always one of childlike joy, like we were getting away with something.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›One sunny day, Dick and I were relaxing on his well-raked beach enjoying a little chat. I took off my boots and Dick noticed how callused the balls of my feet were. Something about the callusing had created a really tender spot, and I was rubbing it.

“You need to do something about that, Pat,” Dick told me. “You have to take care of your feet.”

“What should I do?”

“Lemme see,” Dick replied. Off he went to his tool shed and back he came with a fine wood file. As I leaned back on my elbows, knees bent, he took first one foot, then the other and began to rub off the calluses, gently but persistently.

I remarked, “None of my other friends would do this for me.”

Dick responded with a twinkle, “Then you need better friends.”

Patty Brown, who was a park ranger in Alaska and California for 20 years, worked at Lower Twin Lake from 1990 to 1991. She went on to spend another 20 years teaching science, math and other subjects in Alaska.

To purchase a copy of “Dick Proenneke: Reflections on a Man in His Wilderness,” edited by Alan and Laurel Bennett, go to richardproennekestore.com or amazon.com.