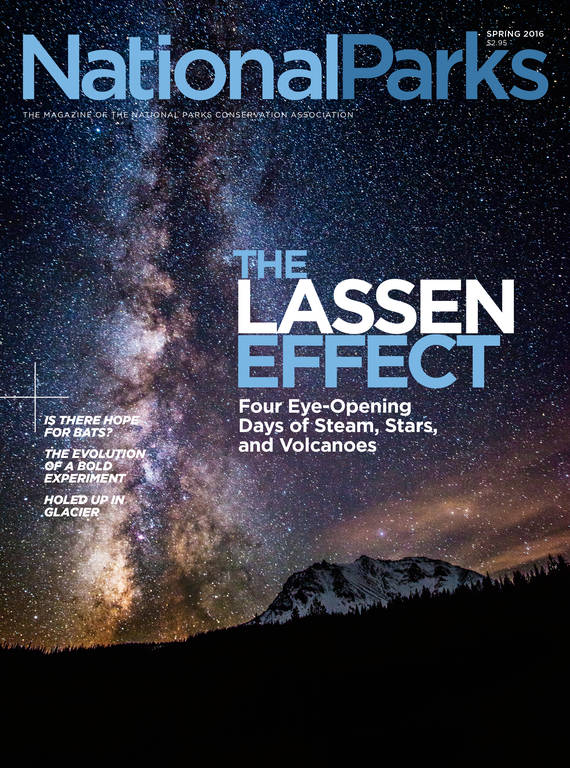

Spring 2016

Landscape Poetry

Artist Tom Killion has spent more than 40 years translating his love of the natural world into intricate, Japanese-style prints.

Since childhood, Tom Killion has considered the poppy-strewn slopes of Tennessee Valley his playground. He and his brother, who were raised in a small town north of San Francisco, would play Revolutionary War on the gentle trail leading to the pebbled beach, dubbing a pile of dirt on the former ranchlands “Bunker Hill.” Later, they would scatter their father’s ashes here in the valley.

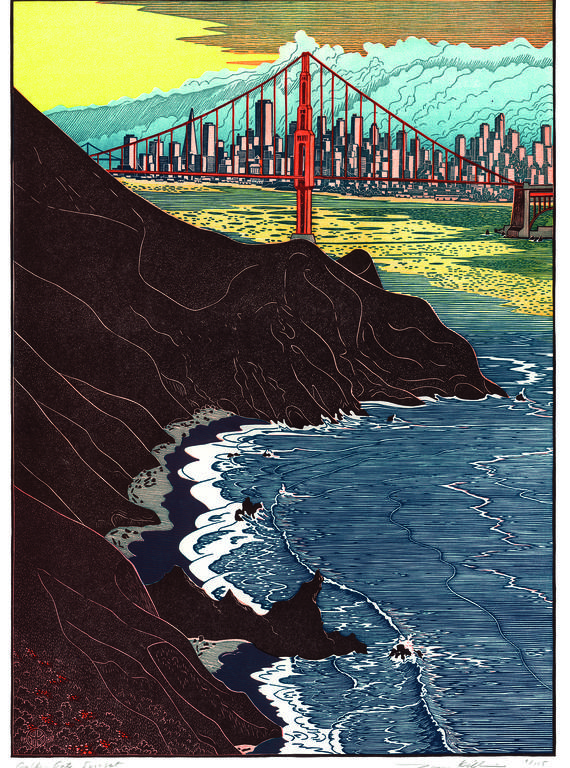

Golden Gate Sunset, 1997.

© TOM KILLIONIn the spring of 2011, Killion returned again to the valley—part of Northern California’s Golden Gate National Recreation Area—and began work on a new print. He quickly drew the pocket beach, cliffs, and the sea, scribbling in the colors and details he wanted to include. He envisioned a bright, Southwestern light in the sky, the clouds rippling and catching the sunset.

But after going through the exacting, 250-hour process of creating the print—which involves transferring the sketch to a key block, carving that block and others to add layers of color, then using a small hand-cranked press to print the image on fine Japanese paper—he wasn’t happy. The yellow was too bright. “I almost threw all that paper away and started over,” he said.

Instead, he kept tinkering using a host of tricks he’d learned in more than four decades of printmaking. He carved more details into his color blocks, inserted bits of wood between the press and the paper to make certain colors pop, and added layers of color. Eventually, the print “took on its own life.”

“When things start going in a certain direction that I hadn’t really planned, I just go with them,” Killion, 63, said on a recent morning in his studio, which sits a few paces from his house and overlooks Tomales Bay in Point Reyes National Seashore. He pointed out the purples, grays, and pinks that backlight the beach, and the sunset light, stippled with golds and greens.

Tennessee Cove, Marin Headlands, 2013.

© TOM KILLIONTennessee Cove and dozens of other seascapes appear in Killion’s most recent book, California’s Wild Edge: The Coast in Prints, Poetry, and History. The book brings together Killion’s wood- and linoleum-block prints, his writings on the cultural history of the coast, and the work of California writers, including Pulitzer prize-winning poet Gary Snyder, who collaborated with Killion on the project.

The printmaker and poet first met in the 1970s. Snyder, now 85, was a hero to Killion, who attended a memorable 1972 reading at University of California, Santa Cruz, which ended with a giant clap of thunder and a power outage. In 1975, Killion took one of the 100 hand-printed editions of his first book to Snyder’s home in the Sierra foothills.

Twenty years later, the pair began their first significant collaboration, a handmade book about the High Sierra. At first sight, the Sierra prints “stole my heart,” Snyder wrote. “He had caught the streams and mountains as they are: visionary and earthy; icy, aloof, and dangerous; but an inspiring teacher when approached the right way.”

Killion said the force behind his landscape art is topophilia—an intense love of place. “I am very visual, and my favorite form of beauty, other than human, is the landscape of western North America, with its wide spaces, open grasslands, and mixed forests,” he said.

Killion’s interest in art was sparked at a young age, when his mother took him to an East Asian art exhibit at San Francisco’s de Young Museum. He recalls being fascinated with the mountains and rivers he saw on the scrolls, which reminded him of his own world on the side of Mount Tamalpais, the 2,571-foot peak across the Golden Gate from San Francisco. Soon after, his parents gave him a book of prints by Hokusai, the Japanese printmaker best known for his series of images of Mount Fuji. “I thought, ‘Wow, I want to make art that looks like that, in my landscape,’” Killion said.

He began making prints in high school; in college, he took letterpress printing classes and produced his first book, a compilation of Hokusai-inspired images of Mount Tam, as locals call it.

After graduation, Killion traveled throughout Europe and Africa, and then attended Stanford University, where he completed a doctorate in African history. He later taught African history at Bowdoin College in Maine, and studied in Eritrea as a Fulbright scholar. Over time, however, he started to wonder why he was so focused on a place not his own. “California really is my homeland, of many generations,” he said. In 1995, he returned to teach African and California history at San Francisco State University.

All along, Killion had been creating limited-edition books of his prints, which captured scenes from his adventures in California and abroad. When Malcolm Margolin, the head of Heyday press, first encountered Killion’s hand-printed High Sierra book in 2000, he was smitten. “It was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen.” he said.

Margolin went on to publish The High Sierra of California, the collaboration with Snyder, which includes Killion’s interpretation of iconic Yosemite scenery, the wilderness backcountry of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, and the region’s junipers, streams, and granite peaks. “I just love the forms in the Sierras,” Killion said. “Each tree and plant and even the rocks—they all have this individuality because it’s such a harsh landscape and you don’t have a whole big forest in a lot of places.” Running alongside the images are excerpts from Snyder’s backpacking journals and writings by naturalist John Muir.

The book raised Killion’s profile, allowing him to retire from teaching to focus on his art. He and Snyder followed up with a book about Mount Tam and the 2015 collaboration about the coast. With each project, Killion has immersed himself more deeply in writing about the region’s history; California’s Wild Edge includes chapters on early exploration by the Spanish turn-of-the-century horseback travelers and poet Robinson Jeffers. “I finally found a way to put history and printmaking together,” Killion said.

For more than three decades, Santa Cruz was Killion’s home base, but in 2003, he returned to Marin County with his wife and two children. His newfound proximity to stretches of undeveloped coastland led to a series of artworks; when he learned that Snyder had also been influenced by the time he spent on this part of the coast, the book took shape. Snyder, a former merchant marine, encouraged Killion to think of the coast as seen from the sea—which led Killion to go deep into seafaring literature, such as Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast, which describes California through a watery lens.

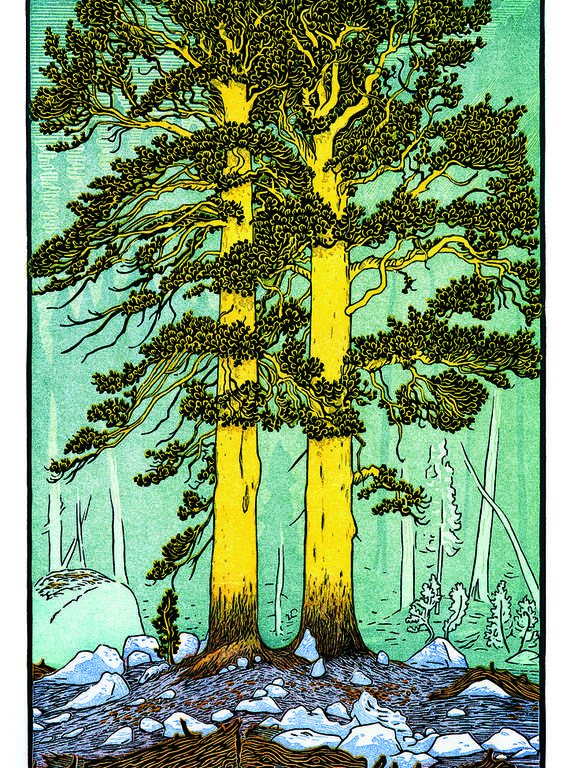

Twin Lodgepole Pines, 2011.

© TOM KILLIONSnyder also inspired one of Killion’s best-known prints. In 2007, the two went on a trip for writers and artists into Sequoia National Park’s Miter Basin. One day, Snyder and Killion hiked to Siberian Outpost, a barren stretch of land dotted with rocks and pines. On their way back, they noticed two lodgepole pines growing side by side, their roots intertwined. Snyder told Killion about a Japanese Noh play in which a devoted older couple becomes a pair of pine trees. Killion later headed back to the spot with a camp chair to sketch the intricacies of the foliage.

In his small shingled studio—crowded with printing blocks, sketches for future projects, a small press, worktables, and carving tools—Killion quickly found the lodgepole print and pulled it out. The golden sheen of the trunks comes from the resinous pitch that the high-elevation trees produce to protect themselves. In the summer “they glow, especially at sunset,” he said. “Just like candles.” The print will likely become part of Killion’s current project, a book on California treescapes.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Most of the book will feature new prints, which will take him back into the mountains and along the coast to sketch. In an artist’s statement, he wrote about his “love for the natural world, the bones of the land, the skin and fur of the plants and trees.” This wild creature is his first and deepest love. “That’s why I make my art,” he said. “It’s the beauty of the real world that I’m entranced with.”

Both those things—the tangible wilderness and representations of it—are critically important, in Margolin’s view. He recalled a talk and slideshow Killion gave at Yosemite’s Ahwahnee Hotel. When the printmaker came to an image of Half Dome, he stopped. “This is ridiculous,” he said. “I’m showing you an image of Half Dome, and it’s right out there.”

But it’s not ridiculous or redundant, Margolin said. “Beauty leads us to knowledge and understanding and to a relationship with the world. If anything is going to save us, it’s not science; it’s beauty, it’s art.” he said. “I think it’s the love of beauty that has created the National Park System. And I think that Tom Killion is a part of that lineage.”