A Century of Impact

Fighting to Keep the Canyon Grand

The Grand Canyon is enormous in every way — 277 miles long, 18 miles across at its widest point and a mile deep, revealing 2 billion years of geological history — but the place it holds in our collective memory is immeasurable.

To the Havasupai (Havasu ‘Baaja), the people of the blue-green water — just one of Grand Canyon’s traditionally associated tribes — it is the homeland entrusted to them by the Creator since time immemorial. To many other Americans, it is the landscape — vast, complex, beautiful — that defines not only the Southwest but the spirit of an entire nation. And to people the world over, it is a singular wonder — the most spectacular gorge on the planet — enshrined as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

It’s a truly astonishing sight. And it’s hard to imagine a place more obviously deserving of protection.

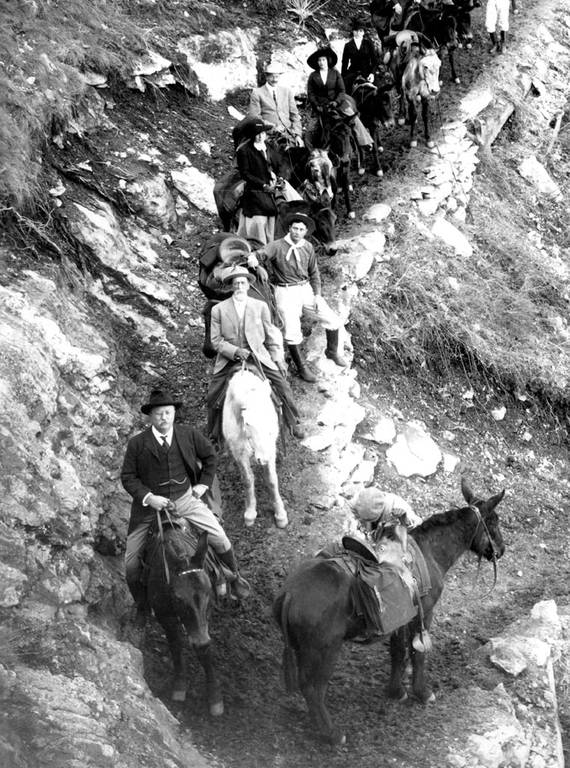

Teddy Roosevelt and the Colgate Party start down the Bright Angel Trail in Grand Canyon.

Grand Canyon National ParkYet the Grand Canyon, carved by the Colorado River over the past 5 or 6 million years, has seen the growing impact of human activity over the past century — threats that continue to this day.

President Theodore Roosevelt understood that this place, for all its magnificence, was not immune to exploitation. To stave off encroachment by those seeking to profit from its grandeur, he sought to protect the Grand Canyon as a national park but initially was met by opposition from Congress.

So, in 1908, using his executive authority under the Antiquities Act, Roosevelt established Grand Canyon National Monument, safeguarding what he considered “a natural wonder which is in kind absolutely unparalleled throughout the rest of the world.”

I want to ask you to keep this great wonder of nature as it now is,” he said. “Leave it as it is. You cannot improve on it; not a bit. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it. What you can do is keep it for your children, your children’s children, and for all who come after you…

On February 26, 1919, a month after Roosevelt’s death, an act of Congress that furthered his vision was signed into law, establishing Grand Canyon National Park. Just 12 weeks later, on May 19, 1919, the National Parks Association — known today as the National Parks Conservation Association — was formed, and we’ve been fighting to keep the canyon grand ever since.

Through the Great Depression and Second World War, the park received only a modest number of visitors and even fewer resources, leaving its roads, trails and buildings in disrepair. By the 1950s, amid the postwar economic boom and a renewed and growing interest in America’s national parks, more than a million visitors found their way to Grand Canyon each year. And as the population of the Southwest grew, the Colorado River Basin’s precious reserves of minerals and water left it vulnerable to extraction and development.

By the early 1960s, a serious threat emerged: proposed hydroelectric dams in both Marble Canyon and Lower Granite Gorge, projects that, if completed, would have forever changed the character of the Grand Canyon. NPA, always a staunch defender of the integrity of the parks, joined allies like the Sierra Club and entered a four-year struggle to defeat the dams through focused outreach and policy work — highlighting the issue in National Parks magazine, petitioning the Federal Power Commission, and conducting studies of the engineering and economic feasibility of the proposals that would ultimately influence the outcome. The immediate threat ended when the Johnson administration withdrew its support for the water projects but, as a compromise, an alternative plan — the construction of a nearby coal-fired power plant — was approved.

NPCA collaborated with the Navajo environmental group Dine’ CARE to produce a video that raises the profile of native voices advocating for better air quality in the Southwest.

The Navajo Generating Station in Page, Arizona — the massive power plant built in lieu of the proposed dams — was widely seen as the lesser of two evils at the time. But situated just 12 miles from the boundaries of Grand Canyon National Park, the facility, one of the dirtiest in the country, became a constant source of sulfur dioxide emissions, fouling the air for millions across the Southwest and plaguing the park for decades. When the winds blew toward the park, noxious industrial haze would settle over the canyon, dramatically reducing visibility and creating unhealthy air conditions for millions of visitors drawn to what should have been the Grand Canyon’s sublime vistas.

In 2014, after sustained pressure on the Environmental Protection Agency, NPCA and coalition partners challenged the EPA’s failure to uphold the standards of the Clean Air Act and protect the Grand Canyon — a ruling that would have allowed the coal-fired plant to continue to pollute for decades. In 2017, the operators announced that the Navajo Generating Station would close in 2019 — a quarter-century ahead of schedule — allowing both park lovers and residents of the region to breathe a little bit easier.

Just as vulnerable as the Grand Canyon’s air is its water. Like much of the Colorado Plateau, the canyon is rich in uranium, first discovered by prospectors in the 1890s and later the object of a Cold War-era mining boom that stretched from the 1950s until prices fell in 1969. But mining operations left in their wake hazardous radioactive materials and contaminated soils, aquifers and drinking water — cause for great concern when uranium prices rose again in 2006 and new mining claims were filed in watersheds draining directly into the Colorado River and Grand Canyon National Park.

For five years, NPCA staff worked tirelessly to block new claims, publishing a critical report, testifying before Congress and collecting the comments of 85,000 park advocates. In 2012, those efforts paid off when Interior Secretary Ken Salazar ordered a 20-year moratorium on thousands of new mining claims — safeguarding the health of the canyon and the local communities whose water supplies were at risk.

Since Roosevelt’s day, developers have had designs on the Grand Canyon, but two recent proposals were beyond the pale. One, a planned mega-development that would have transformed the tiny gateway community of Tusayan into a sprawling, multi-use complex, was considered by the Park Service to be one of the greatest threats in the history of Grand Canyon National Park — and a clear threat to the groundwater feeding the Grand Canyon’s creeks, seeps and springs. Another, the Escalade development, would have sited a resort hotel and tramway on Navajo land right on the rim of the Grand Canyon, at the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers — an ecologically important site held sacred by many of the region’s tribes.

NPCA adamantly opposed both proposals. In 2015, NPCA and its coalition partners urged the U.S. Forest Service to turn down the plan that would pave the way for the Tusayan project, flooding the department with over 200,00 comments from concerned citizens. A year later, the Forest Service rejected the proposal, setting a high bar for the park’s protection. And in 2018, after rallying supporters to ask the Navajo Tribal Council to reject the Escalade proposal, NPCA celebrated the unanimous vote by the Bodaway/Gap Navajo chapter that finally stopped the development cold.

Successes like these are hard-won and worth celebrating. But while the consequences of the challenges we face can be dire, even irreversible, no victory is ever fully assured. In 2017, the 20-year moratorium on Grand Canyon uranium mining was targeted by the Trump administration — even though nonpartisan polls showed that 80% of Arizona voters and 80% of all Americans supported permanent protection from new mining — before being overruled by the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, which upheld the Interior Department’s ban. Still, other public lands in the region, such as Bears Ears National Monument — which the Trump administration, despite great public opposition, reduced by 85% in 2018 — remain vulnerable to a rising number of mining claims on, and even within, their shrinking borders.

Two things are for certain: More threats will come and, when they do, NPCA will be there to defend the parks against them — in the courtroom, before Congress and in local communities with our partners beside us.

Make a tax-deductible gift today to provide a brighter future for our national parks and the millions of Americans who enjoy them.

Donate Now