Support the Fund that Improves and Protects Public Land

As a child, I was inspired by the landscapes, night skies, and historic treasures in our national parks. As an adult with a career protecting these places, I was stunned to learn that many of these same national parks I enjoyed exploring as a boy are threatened by trophy homes, luxury hotels, and mini-marts, not just near, but inside their borders.

How can people build mansions, stores, and other inappropriate buildings in world-famous landscapes like Zion or Grand Teton? It boils down to chance—and the effects can be irreversible.

When Congress or the president designates a national park site, there are often land parcels within these larger landscapes that remain privately owned, even though they may be surrounded on all sides by public land. When a landowner decides to sell one of these properties, it can be purchased as a building site for a home or commercial development, just like with any other property.

These kinds of developments create a multitude of problems, from disrupting the native ecology of a landscape to physically blocking wildlife migration. Most obviously, these new buildings are eyesores that destroy the character of natural scenery and historic battlefields and create conflicts with hikers and other visitors looking to explore and enjoy their public parks.

Thankfully, Congress pioneered a program 50 years ago called the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) to protect these vulnerable parcels within national parks and other federal lands while compensating landowners fairly.

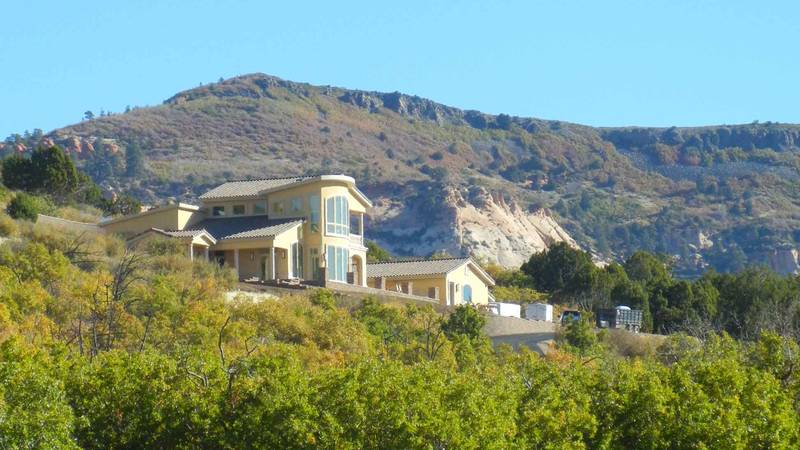

This home at Zion National Park was built on land that could have been protected with the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

Photo © Cory MacNulty/NPCAThe concept is simple. When energy companies drill for oil on federal offshore waters, the government sets aside a small portion of the royalties they collect to buy these threatened land parcels from willing sellers. This way, when private companies profit from federal lands that belong to all Americans, Americans can also profit from an improved public lands system that supports public health, natural beauty, historic preservation, and strong local economies.

LWCF has a solid track record of success. A couple of years ago, developers were eyeing four acres in Harper’s Ferry National Park as a possible location for a large service station and mini-mart, among other proposals. Money from LWCF helped save the historic integrity of this iconic Civil War park.

Similarly, inside Grand Teton National Park, the state of Wyoming owns parcels of land that officials plan on selling by 2016. LWCF funds helped protect 86 acres along the majestic Snake River in 2012, although hundreds more acres of land at this landmark park remain seriously threatened.

Right now, however, the entire conservation program is vulnerable. If Congress doesn’t act, this fund will expire on October 1, leaving many of our national parks open to potential ugly intrusions like condos, gas stations, and private villas.

If Congress does not prioritize money for LWCF, the stakes are literally huge: 2.2 million acres of vulnerable lands exist within the National Park System alone—that’s almost 3,500 square miles! And there is even more acreage in national forests, national wildlife refuges, and other protected areas.

The threat at Grand Teton National Park in particular is pressing and serious. Though LWCF successfully protected prime riverfront land there in 2012, the state of Wyoming would like to sell more than a thousand additional acres. The Department of the Interior entered into an agreement to purchase these properties, but the deadline is fast approaching in 2016 to finalize details and complete the deal. The agreement dictates that if the deadline is not met, the state will sell these lands inside Grand Teton National Park, as required by state law. What would happen to those lands if they fall into private ownership is anyone’s guess.

This very real threat is exactly why LWCF was created. Inappropriate development can forever change some of America’s most beloved landscapes—the places we loved as children and hope to bring our own children to enjoy someday. There is simply too much to lose.

About the author

-

John Garder Senior Director of Budget & Appropriations, Government Affairs

John Garder Senior Director of Budget & Appropriations, Government AffairsJohn Garder is Senior Director of Budget & Appropriations at NPCA. For fifteen years, he’s been a budget analyst and advocate for more adequate funding for the National Park Service, speaking with diverse audiences, including media outlets, Congress, the White House, and the Department of the Interior.