Most of Congaree National Park lies within the floodplain of two rivers and floods about 10 times a year. The nutrients the water washes in creates a natural wonder like no other.

About a half hour’s drive from the bustle of Columbia, South Carolina, majestic bald cypress, water tupelo, cedar and pine trees grow to astonishing heights. Nutrients washed in by the floodwaters of two rivers create one of the country’s most distinctive ecosystems, now preserved as Congaree National Park.

Bordered by the Congaree and Wateree rivers, this park harbors the largest intact expanse of old-growth, bottomland hardwood forest remaining in the U.S. It also contains an upland forest of longleaf and loblolly pines — “upland” being relative, as this park’s highest elevation is just 140 feet above sea level.

Congaree’s 26,000 acres of wilderness reflect what much of the Southeast looked like prior to the arrival of Europeans, who farmed, logged and developed the area. Old-growth bottomland forests once covered about 30 million acres, while longleaf pine savannahs covered about 90 million acres.

And these trees are tall!

The forest’s canopy height averages more than 100 feet, and the tallest tree is a 170-foot loblolly pine with a circumference of over 15 feet. Some trees rise so high they have been judged as “champion trees.” This means that they have been determined to be the largest of their species at a given time in the state or nation, according to formula based on trunk circumference, height and crown spread.

According to the National Park Service, Congaree contains the highest concentration of champion-sized trees anywhere in North America.

Floodplain forests like Congaree’s thrive in areas that cycle through wet and dry periods. Unlike a swamp, which stays water-filled year-round, a bottomland floodplain periodically gets covered by water from the streams or rivers it borders. Almost 80% of Congaree National Park lies within a floodplain, and the park floods about 10 times a year. These forested wetlands, slow-moving creeks and oxbow lakes (formed by abandoned bends in the rivers and streams) provide a rich habitat for aquatic life.

10 Parks for Every Tree Lover’s List

National parks are home to some of the country’s rarest and most remarkable trees. In many cases, these spectacular plants have stood watch over centuries of history. Here are…

See more ›Visitors come to Congaree to hike, kayak, fish and camp — with spring, fall or winter being the best months to explore the park because of the mild temperatures. There are fewer mosquitoes then, too. The park recommends bringing insect repellent along when visiting in the mid-spring to mid-fall.

Once a less-known park in the National Park System, Congaree was among 20 parks that broke annual visitation records in 2023. The secret is out — with 250,114 visits last year, Congaree has experienced a 57% jump in visitation since before the COVID-19 pandemic. Even visits during the summer months are up, according to the park. Public viewing of synchronous fireflies has become a signature event for two weeks in mid-May to mid-June, with admission through a lottery system.

As USA Today pointed out last July, Congaree is just a few hours from Charleston, Greenville, Charlotte and Atlanta, making it an easy weekend trip for many people.

Raised boardwalks allow visitors to stroll through the park’s lowland areas and see the towering trees up close. Cypress knees protrude from watery pools, and switch cane and dwarf palmetto plants thrive in the wet, sandy soil where sunlight strikes through the canopy. Dead trees, called snags, provide homes for the park’s many bird species, insects and fungi. Moss can be seen growing on the lower portions of the trees, indicating the water level of previous floods.

For paddlers, the 15-mile Cedar Creek Canoe Trail winds through the old-growth forest, and the 50-mile Congaree River Blue Trail flows from Columbia downstream to the park.

Hiking trails in the park’s upland regions meander along river bluffs and through longleaf pine forests, which the Park Service manages with prescribed fires that encourage the trees’ growth. With little elevation change in the park, many trails are flat and rated as easy — although some backcountry trails are rated as difficult.

In 1983, UNESCO designated Congaree National Park a biosphere region for these old-growth forests — and also for its distinctive cultural heritage. As part of the area’s human history, African Americans hid from slavery in the dense woodlands in the 1800s. Called maroons, they lived in the wilderness, oftentimes for years, to avoid enslavement at nearby plantations, while others sought refuge here temporarily on their way north. After the Civil War, freed people established towns in the area.

A robust logging industry operated here in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and resumed for a brief time in the 1960s, with the trees used for ships, railroads and buildings.

The park’s forest might have disappeared to logging and development without the efforts of journalist and conservationist Harry Hampton, for whom the park’s visitor center is named.

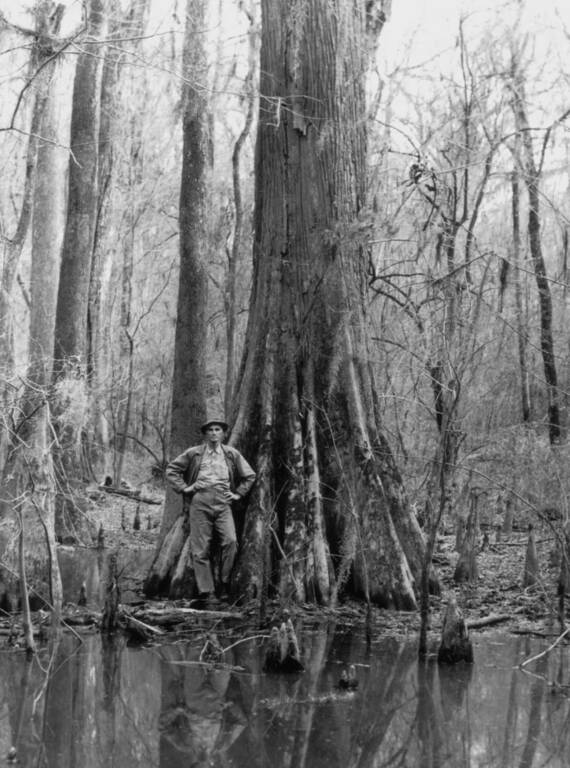

Harry Hampton pictured next to one of the giant bald cypress trees in what would become Congaree National Park.

NPSHampton often hunted in the floodplain and, recognizing the distinctive characteristics of the forest and its wildlife, started advocating in the 1950s for their protection. His work inspired a successful citizen action campaign in later years, and Congress established Congaree Swamp National Monument in 1976. Congaree was redesignated a national park in 2003.

Congaree has two sides. Most people visit the park’s western side, where the visitor center, campgrounds and boardwalk trail are located. The eastern side is worth exploring, too. For hikers, the Bates Ferry Trail follows a historic road likely used by Native Americans before Europeans arrived. Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto’s expedition passed along here, as did Gen. William T. Sherman and his soldiers as they marched across South Carolina in 1865 near the close of the Civil War. Newly installed waysides along the trail tell of the park’s significance during the American Revolution.

The park has its threats. The Park Service says climate change is affecting Congaree’s weather patterns, as well as how its plants grow and animals behave. Invasive feral hogs make a mess in the park as they “root” in the forest, tearing up soil and leaves.

The Wild Congaree

Paddling the Blue Trail to South Carolina’s only national park.

See more ›The feral hogs normally aren’t a danger to visitors, but as with any wild animal, the Park Service warns visitors to not approach or harass them. They are believed to have descended from escaped food animals brought to North America by Europeans in the 1500s. The Park Service periodically manages their population through hunting.

Want to visit?

Congaree National Park is about 20 miles outside Columbia, South Carolina — which is located approximately 130 miles west of the Atlantic Ocean and approximately 150 miles southeast of the Appalachian Mountains. The park is open year-round and has no entrance fee. Because water levels fluctuate, check out the current conditions before heading to the park.

Stay On Top of News

Our email newsletter shares the latest on parks.

About the author

-

Linda Coutant Staff Writer

Linda Coutant Staff WriterAs staff writer on the Communications team, Linda Coutant manages the Park Advocate blog and coordinates the monthly Park Notes e-newsletter distributed to NPCA’s members and supporters. She lives in Western North Carolina.

-

General

-

- Park:

- Congaree National Park

-

- NPCA Region:

- Southeast

-