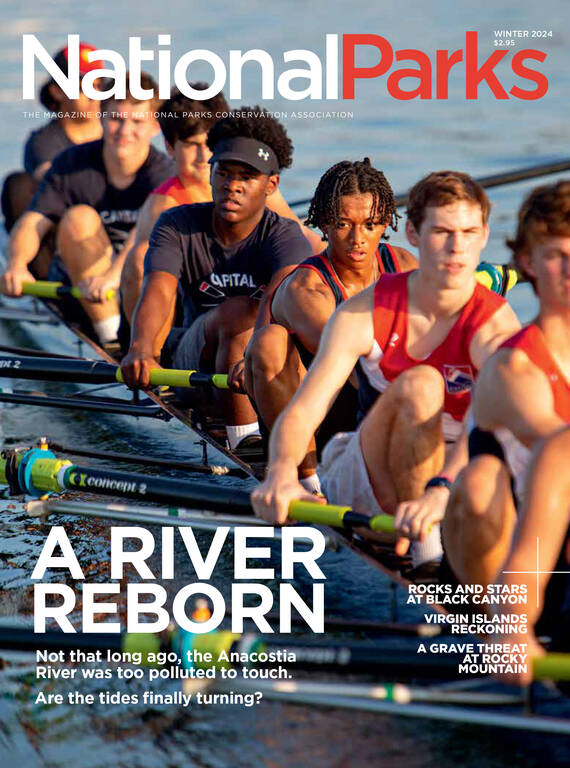

Winter 2024

‘In My Country’

More than a century after Native Americans were displaced to create Glacier National Park, a Blackfeet-run tour company offers visitors a chance to see the park from the perspective of the people who lived there first.

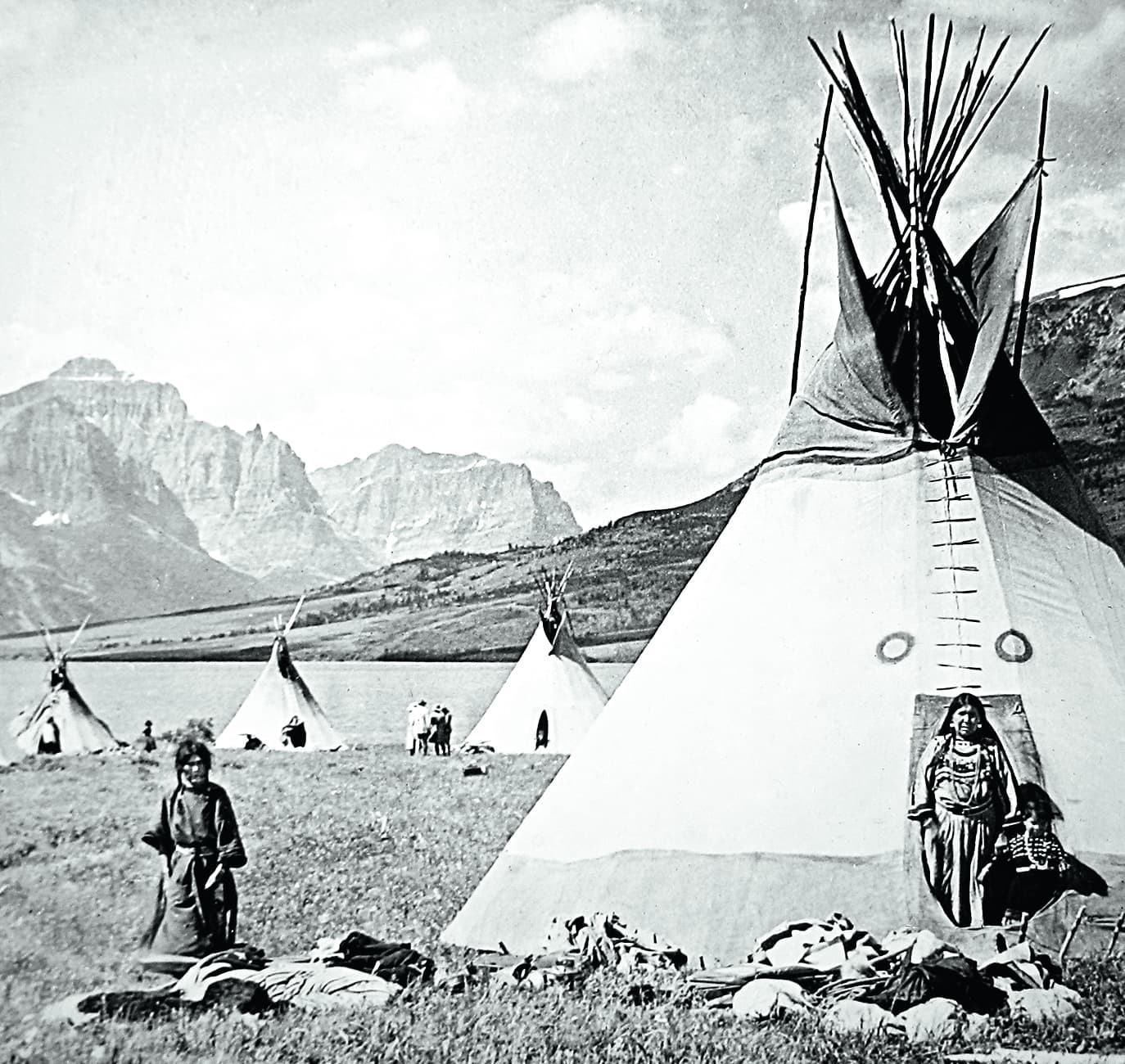

When it came to promoting its hotels and chalets in Glacier National Park, the Great Northern Railway found the Blackfeet enormously useful. After the park opened in 1910, Great Northern hired photographers and artists to capture portraits of the Blackfeet and their scenic camps. They urged tourists to come see “Glacier’s vanishing Indians.” They hired Blackfeet families to erect tipis outside Glacier Park Lodge and paid them to dress in ceremonial regalia and greet arriving trains.

Not included in this publicity was the fact that most of Glacier was, until 1895, part of the Blackfeet reservation. It went unmentioned that the U.S. government negotiated the purchase of this land at a time when the Blackfeet had been weakened by smallpox, famine and the strategic slaughter of the bison that sustained them. Great Northern’s postcards and calendars made no reference to Glacier’s disputed boundaries or the fact that the Tribe stood to gain almost nothing from this bourgeoning tourist economy.

“I don’t think they ever really asked these Native people about their connection to the land,” says Kevin KickingWoman, a high school teacher from nearby Browning and an enrolled member of the Blackfeet Tribe. “It was mostly about posing.”

TOURISM AND THE BLACKFEET

This history is part of what drives KickingWoman, who pulls up to Glacier Park Lodge in a white minibus at 8 o’clock one bright summer morning more than a century later. He steps off the bus dressed in shorts, a windbreaker and a Panama hat, with a beaded medallion around his neck. KickingWoman is a guide for Sun Tours, the first and only company to offer Blackfeet-led interpretive tours of Glacier, and one of the only Native-owned tour businesses to operate within a national park. Now in its 31st year, Sun Tours offers half- and full-day guided trips in the park, part of the ancestral homeland of multiple Tribes, including the Blackfeet and the Kootenai.

Tourists file out of the lodge’s Paul Bunyanesque lobby, and KickingWoman checks them in for the day’s tour. There’s a couple from Wisconsin, a family from Virginia, a pair of barbecue sauce purveyors from Florida, a handful of Minnesotans, an Australian woman and an Englishman.

Once everyone is aboard, KickingWoman takes his seat behind the wheel, adjusts a microphone to his mouth and introduces himself in the Blackfoot language. “You’re in my country now,” he continues in English, “so I’m going to greet you in my tongue.”

KickingWoman turns the bus north and drives past Lower Two Medicine Lake where he points out a Blackfeet lodge — a tipi, to use the Sioux word — on the green plains ascending toward Appistoki Peak. He explains how Blackfeet lodges, which are made out of cured lodgepole pines and canvas (but used to be fashioned from buffalo hide), are passed down through the generations. The lodges got bigger with the arrival of horses in the early 1700s, when they could be dragged on travoises, but they were always portable, designed to move with the seasons like sunlight across a landscape that had never known a fence.

Blackfeet Lodges are passed down from generation to generation and were designed with portability in mind. ©KGPA LTD/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

As he drives the bus along the eastern park boundary, KickingWoman starts in on an unflinching history lesson beginning with the Catholic Church’s decree in 1452 that allowed for the enslavement of non-Christian people. Some 300 years later, the U.S. Declaration of Independence described Native Americans as “merciless Indian savages.” In 1924, KickingWoman adds, “we got to be citizens of our own country.” Meanwhile, the Dawes Act broke up reservation land, and an abusive boarding school system, in which Native children were taken from their families and stripped of their language and culture, continued into the 1970s.

At this point KickingWoman pulls the bus over at a wide turnout where the shaggy forested foothills give way to Rising Wolf Mountain and Red Mountain. “You guys can get out here and do an ooh and an aah,” he says.

KickingWoman was born and raised on the Blackfeet Reservation. At 18, he went to what was then called Haskell Indian Junior College, and subsequently joined the U.S. Navy. He served in the Persian Gulf War, and then returned to Montana where he worked as a firefighter and a corrections officer before getting a degree in linguistics, cultural anthropology and music ethnology. Today, he’s one of only several hundred semi-fluent speakers of the Blackfoot language in the U.S. He teaches the language and Blackfeet history at Browning High School, and for the last four years he’s been a guide in Glacier for Sun Tours. “I love the power and energy of this place,” he says.

We’re Still Here

Every national park site sits on ancestral lands. So what does it mean to be a Native American working for the Park Service today?

See more ›A few minutes later, the bus is climbing through silvered dead pines, past beargrass and yarrow, to the boundary of the Blackfeet Reservation at the park entrance, where the wind whips Saint Mary Lake into a froth and keeps the U.S., Blackfeet and Canadian flags snapping on their poles. As we drive along the lake, KickingWoman explains the natural history of this glacial valley, describes the region’s medicinal plants and tells Blackfeet stories about Napi, the creator of the animals and the earth. In the middle of a discourse on Blackfeet cosmology, and how Polaris is the bellybutton of the universe, KickingWoman interrupts himself to point out a marsh where he often sees moose.

We continue up Going-to-the-Sun Road, lined with lupine and Indian paintbrush, past Siyeh Bend, all the way to Logan Pass, where some of us scramble along the snow-covered boardwalk toward Hidden Lake as tawny bighorn sheep browse on neon-yellow glacier lilies.

The Blackfeet call the Glacier area Mo’kakiikin Miistakiiks, or the Backbone of the World. “We refer to these mountains as grandfathers,” KickingWoman says. “We believe they are energy. They have lives.”

In 1895, their population nearly decimated, the Blackfeet sold 800,000 acres to the U.S. government for $1.5 million. Today many Blackfeet argue that a surveying error cheated them out of 45,000 acres and, moreover, that the land wasn’t sold but offered to the government on a 99-year lease. The agreement of 1895 guaranteed the Blackfeet the right to hunt, fish, cut wood and gather plants on the land, although those rights essentially vanished after Glacier National Park was created in 1910. Disputes over Glacier’s boundaries continue to this day.

We refer to these mountains as grandfathers. … We believe they are energy. They have lives.

The clouds have come in low as we begin our descent back down the highway, but they clear long enough for KickingWoman to point out Heavy Runner Mountain. KickingWoman tells the story of Chief Heavy Runner and his band, who were camped on Bear River (east of what is now Glacier) one frigid winter morning in 1870 when the U.S. Army attacked, killing over 200 men, women and children before burning their lodges. Chief Heavy Runner was among the dead, shot while holding papers declaring him “a friend to the whites.”

After the story, KickingWoman starts to sing Chief Heavy Runner’s song as we listen in silence. The tune is rhythmic and mournful, a song with no words, just wailed syllables heavy with feeling. KickingWoman wrote his master’s thesis on Blackfeet songs, and this is one of many he sings on the tour. “The more songs you know, the more you can help people,” he says. “I’m kinda like the Native Susan Boyle of Indian Country.”

The idea of a Blackfeet interpretive tour of Glacier faced stiff opposition at first, founder Ed DesRosier told me later that day in Sun Tours’ breezy two-story headquarters. In the early 1990s, DesRosier was a young man working for the Montana highway department in East Glacier. An enrolled Blackfeet member, he felt severed from the park, where he’d grown up camping and finding flint arrowheads and buffalo bones with his parents and grandparents. When he saw the park’s iconic red jammer buses, it rankled him. It didn’t feel right that Glacier’s tourism economy was dominated by non-Native businesses, including the red bus tours. Glacier Park Lodge itself sits within the Blackfeet Reservation, on land the U.S. government sold to the Great Northern Railway for $30 an acre.

‘How We Heal’

The Blackfeet Nation’s effort to restore bison reached a milestone this summer with the release of a free-roaming herd onto sacred lands adjacent to Glacier National Park.

See more ›“I realized there’s money to be made,” DesRosier said, “and this big corporate entity is making money off the lodging, the food, the tours, the gift shops.”

So DesRosier printed brochures and licensed his business. Then he went to the park superintendent. “This has been our home forever,” he told him. “There’s not a tour company telling that story.”

The superintendent sent him to the tour bus concessionaire, who offered him a job as a driver. “I’m not really looking for a bus driving job,” DesRosier said.

Convinced that the agreement of 1895 gave him the right to be a park tour guide, DesRosier recruited a cousin and a high school friend. They started taking tourists into the park in a Ford passenger van. Immediately, rangers booked them for operating without the proper paperwork. Eventually, all three were fined, threatened with misdemeanors and given notices to appear before a federal magistrate, who subsequently found them guilty. The Blackfeet Tribal council paid for an attorney to appeal the case to the federal district court, which also found them guilty, and then to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, the last stop before the Supreme Court.

“Our legal team put together an incredible case built upon the agreement of 1895, the history of the Blackfeet, the rights that were recognized translated to the modern world of a business model, the right that Glacier would give us to survive, basically,” DesRosier said.

Meanwhile, DesRosier and others staged protests around Glacier, holding signs that accused the park of being anti-Native American and monopolistic. Eventually the Park Service caved and allowed Sun Tours into Glacier, rendering the court case moot.

“Since then, we’ve been in the good graces,” DesRosier said.

As park visits climb and more people seek out unique cultural experiences, Sun Tours is busier than ever, now with a fleet of 10 buses. And they don’t just guide tourists. Last fall they brought 22 Blackfeet youth on a tour, more than half of whom had never been in the park before. This year, the entire student population of a local elementary school got on a bus, and for the first time, the Park Service hired Sun Tours to give a tour to about 40 interpretive rangers.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Back in the bus, as we wind our way to the final stop, KickingWoman invites questions from his passengers and gives us a playful quiz on what we’ve learned.

“Is Glacier what you expected?” he asks.

“No, it’s better!” says a woman from Duluth. “It’s more.”

Even today, it’s not hard to find in Glacier the same misguided Native American nostalgia that Great Northern Railway was promoting more than a century ago. Decorations in Glacier Park Lodge include a plastic statue of a man in a war bonnet called “Indian Joe,” and two lampposts outside the front doors are carved to look like totem poles, which have no relevance to Blackfeet culture. “It’s like we’re not real,” KickingWoman says. “Like we’re just in the imagination of city folk.” But for those who are interested, Sun Tours offers daily proof that “Glacier’s vanishing Indians” are still here and still connected to this place.

Before pulling up to the lodge, KickingWoman sings us one final song, a song of gratitude. “If I could go back,” he says, “I wish we all had our language. That’s our defining characteristic. Our language derives from this earth. That’s who we are. And our songs. Our songs bring things to life.”