Get a taste of wilderness remarkably close to Chicago and other urban centers at Indiana Dunes National Park, which NPCA has been helping to preserve and enhance.

With 15 miles of Lake Michigan coast and 15,000 acres of landscape, the distinctive setting of Indiana Dunes National Park takes visitors from sand dunes to woodlands, marshes to remnants of once-vast prairies. There’s plenty to see and do at this park about an hour’s drive from downtown Chicago or South Bend, Indiana — and an even shorter distance from nearby Pullman National Historical Park.

Indiana Dunes, located in the Hoosier State, has been known by two names. It was established in 1966 as Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore and then became Indiana Dunes National Park in 2019. The park offers plenty of outdoor activities — hiking, biking, beach-going and swimming, camping, fishing, bird watching and horseback riding — and with help from NPCA has been working to improve its visitors’ accessibility both to, and within, the park.

The park ranks among the top 10 most visited national park areas in the country, with its scenic beaches drawing nearly 3 million people from around the world each year. But there’s much more than sunbathing on a Great Lakes shoreline that distinguishes this national park.

Based on National Park Service information and NPCA’s advocacy, here are nine distinctive features you may not know about at Indiana Dunes.

1. One of North America’s most biologically diverse places

Indiana Dunes is considered one of the most biologically diverse places on the continent, and its intricate ecosystems led to its establishment within the National Park System.

Visitors have seen more than 350 species of birds, many of which use the park for feeding and resting as they migrate. The park has over 1,100 flowering plant species and ferns, including bog plants and native prairie grasses, white pines and rare forms of algae. Many of Indiana’s plant species that are listed as rare, threatened, endangered or of special concern can be found here.

A group of swamp white oak leaves at Indiana Dunes National Park.

NPSThe park’s diverse habitats support many types of wildlife. Nearly 50 species of mammals live here, such as white-tailed deer, beavers, racoons, southern flying squirrels, Norway rats, little brown bats, chipmunks, rabbits and red foxes to name a few. More than 70 species of fish, 60 species of butterflies, 23 species of reptiles and 18 species of amphibians have been identified.

Protecting this treasured landscape and the species that inhabit it is a collaborative effort. In a new report (pdf), NPCA and its partners have outlined an approach for continuing the work to restore native habitats for species within the national park and surrounding areas.

2. Public transportation to — and greater accessibility within — the park

Unlike most national parks, Indiana Dunes has bus and train service as well as car access to its magnificent landscape. Gary, Indiana’s bus route 13 takes visitors into the park, and the South Shore railroad that runs between Chicago and South Bend offers four stops within the park with trail access from those stops to major park facilities. Rail service will be enhanced by a second track project, slated for completion in 2024.

NPCA has successfully advocated to allow bikes on certain trains during peak season so visitors can make better use of the park’s 37 miles of bike trails.

Soon the park will be connected to a far more extensive network of multiuse trails thanks to the Marquette Greenway, a path for bikes and pedestrians with some sections under construction and others already complete. The pathway could eventually link Indiana Dunes to Pullman National Historical Park, an accessibility feature NPCA has called for since 2015 because it would connect Chicago’s South Side to more green space and a system of safe pedestrian trails.

As well, the park has improved the accessibility of its visitor and education centers and enhanced visitors’ ability to explore beaches and trails through specially designed wheelchairs.

3. Sand dunes nearly 200 feet tall

As the mile-thick Wisconsin glacier retreated 11,000 years ago and formed the Great Lakes, it crushed bedrock into rubble and sand. The water levels of what’s now Lake Michigan rose and fell, creating as many as seven different shorelines — the oldest shorelines moving farther and farther from the water’s edge.

Wind sculpted the shoreline sand into layers of dunes, and wetlands formed in their valleys. Over time, plants took hold in the older dunes — first grasses and later shrubs and trees — eventually growing into forests. Four stages of dunes can be seen today, with some reaching 180 feet.

Lake Michigan’s wind and waves continue to shape the dunes. Seasonal changes, shifts in the lake’s currents and the formation of ice all affect a beach’s slopes.

4. Tree-dotted prairies called black oak savannas

Eastern hardwood forests meet western tall-grass prairies in a landscape called black oak savannas. Development and neglect have endangered these ecosystems, so Indiana Dunes is one of the few places in the world where they can still be seen.

If not managed properly, oak trees will quickly dominate a landscape’s prairie plants, which thrive in sunlight. In the past, lightning strikes and fires intentionally set by Indigenous people to manage the landscape kept the understory within control. Now, the National Park Service protects and restores these ecosystems in the park through prescribed fires with help from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Save the Dunes, an organization that partners frequently with NPCA.

The savannas’ diverse plants and wildlife represent both the oak forest and tall grass prairies, and some of the flora and fauna is listed as rare, threatened or endangered.

5. A famed wetland known as the Great Marsh

The Great Marsh, an extensive wetland that formed about 4,000 years ago, serves as a critical habitat for migratory and breeding birds. Industrial and residential development have crept into the marsh, reducing its size and splitting it from an open body of water that flowed into Lake Michigan into three separate watersheds.

A great blue heron at Indiana Dunes National Park.

NPSBecause wetlands naturally filter contaminated water and are a proven successful climate resilience measure, the Park Service, NPCA and area universities have partnered to replant native wetland flora in portions of the Great Marsh. They are also removing invasive plants. This initiative allows the beautiful ecosystem’s insects, birds and animals to thrive, while combating erosion.

The popular Great Marsh Trail includes an overlook of the marsh where visitors can see herons, sandhill cranes, egrets, warblers and other birds in their natural habitat.

6. ‘Diana of the Dunes’ and fellow conservationists

Alice Gray, dubbed “Diana of the Dunes,” in an undated photo.

Chicago Tribune via Wikimedia CommonsIndiana Dunes would not exist as a park today if not for Alice Gray, known as “Diana of the Dunes,” and other early 20th-century women who advocated for the dunes’ conservation. They set the stage for later efforts to federally protect the landscape.

Seeking solitude and wanting “a free life,” Gray shunned conventional society by leaving Chicago in 1915 to live along Indiana’s shore. The 34-year-old dressed in men’s clothing, hiked among the dunes and lived in makeshift shacks.

She developed notoriety through the news media of the time, which she later used to amplify her voice as an early speaker in the Save the Dunes movement. The park honors her memory with “Diana’s Dare,” a combination hiking challenge and ghost story.

Other women seeking to protect the dunes from industrialization and residential development in the early 1900s were Bess Sheehan, a prominent and proactive clubwoman known as “Lady of the Dunes”; Drusilla Carr, who used squatter’s rights through two decades of legal battles to protect the land she called home; and naturalist Flora Richardson, who educated others on early preservation practices through her leadership in groups such as the Audubon Society and Friends of Our Native Landscape.

7. Houses from the 1933 World’s Fair

A home constructed from corrugated steel? A house with an airplane hangar? Wildly modern when they were created, the park’s Century of Progress Homes form a neighborhood displayed at Chicago’s 1933 World’s Fair. After the fair, a real estate developer moved the houses to Lake Front Drive to create a resort community. The national park now encompasses that area.

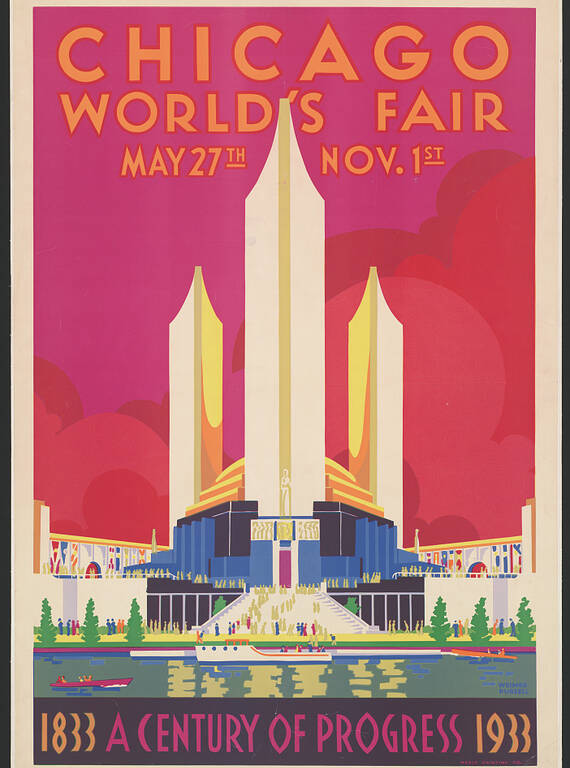

A poster from Chicago’s 1933 World’s Fair.

Library of CongressThe Park Service and the non-profit organization Indiana Landmarks lease the homes to private individuals and families who rehabilitate them. A tour of the homes is held each September and sells out quickly.

The houses demonstrated the latest architectural designs, materials and home technologies of the 1930s — air conditioning and dishwashers among them — and architects’ prediction of things to come. The House of Tomorrow, for example, included an airplane hangar next to the garage based on assumptions that the typical American family of the future would own aircraft.

The House of Tomorrow has been declared a National Treasure by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The 90-year-old home and the park’s 19th-century Bailly Homestead are being stabilized through funding from the Great American Outdoors Act, a congressional measure NPCA advocated for.

8. A national recreational water trail

If paddling to a national park sounds more exciting than public transportation (see No. 2), the 75-mile Lake Michigan Water Trail runs along the lake’s southern shore from Chicago to New Buffalo, Michigan, and has access points in Indiana Dunes. Paddlers can see the park’s diverse ecosystems, high dunes and tree-lined bluffs from the water, as well as pass by urban centers and the Port of Indiana.

The trail is part of the country’s National Water Trails System that conserves and restores waterways through collaboration among federal, state, local and nonprofit groups. Plans are underway to extend the trail around all of Lake Michigan, which would make it the longest continuous loop of freshwater sea kayaking in the world.

9. A state park within a national park

Before sections of the Indiana coastline were designated a national lakeshore in 1966, conservationists succeeded in preserving a portion of the dunes as a state park in 1925.

Indiana Dunes State Park includes more than three miles of beach and more than 2,000 acres of native habitat. It is bordered on three sides by the national park, which has similar landscapes. The state park has its own entrance fee and features a nature center, trails, camping, two beach parking lots and bathhouse pavilion.

Want to visit?

Learn more about Indiana Dunes National Park. Depending on how much time you have to visit, the Park Service provides itineraries for just a couple hours, half a day and one to two days. Nearby attractions include Pullman National Historical Park, which is about 45 minutes away.

Stay On Top of News

Our email newsletter shares the latest on parks.

About the author

-

Linda Coutant Staff Writer

Linda Coutant Staff WriterAs staff writer on the Communications team, Linda Coutant manages the Park Advocate blog and coordinates the monthly Park Notes e-newsletter distributed to NPCA’s members and supporters. She lives in Western North Carolina.

-

General

-

- NPCA Region:

- Midwest

-

Issues