Summer 2023

Remembering Rosenwald

With Booker T. Washington’s help, Julius Rosenwald built 5,000 schools for Black students across 15 Southern states. Why do so few people know his name?

Mostly, what Newell Quinton knew about his boyhood school was that he loved it.

The Sharptown Colored School community was an extended family to Quinton and his seven siblings. All of their teachers lived nearby in San Domingo, a Black enclave outside of Sharptown on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. On cold days, a potbellied stove heated the rooms. On warm ones, two ancient oaks offered shade in the front yard. In the back, a softball field provided a rare place in segregated Maryland for young Black boys and girls to slide into home plate. Light flowed in from two walls of windows, while large, rectangular chalkboards hung on the interior walls. The pine floors often glistened from recent coats of linseed oil.

Quinton’s parents had attended the school, too, and his grandparents had helped build it. So, after he retired from a career at the Department of Veterans Affairs in Baltimore and returned to his father’s farm in San Domingo to raise pigs and goats, he began to think about restoring the weathered building and turning it into a community center — a tribute to a place where Black children had thrived.

That’s when Quinton, 79, learned his beloved alma mater was a historic Rosenwald school, one of almost 5,000 built between 1912 and 1932 across 15 Southern states. The undertaking was a partnership between Black scholar Booker T. Washington, head of Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, and businessman Julius Rosenwald, the president and eventually chairman of Sears, Roebuck and Co. in Chicago. About one-third of all the Black children in the South were educated in these schools during the time they were active. Many graduates, including Quinton and his siblings, would go on to join the Civil Rights Movement.

“I had no idea,” Quinton said of Rosenwald’s name and legacy. “I was just amazed and grateful. Had it not been for these two people, with their unselfish approach to life, who said, ‘What can we do?’ then I have no idea what would have happened.”

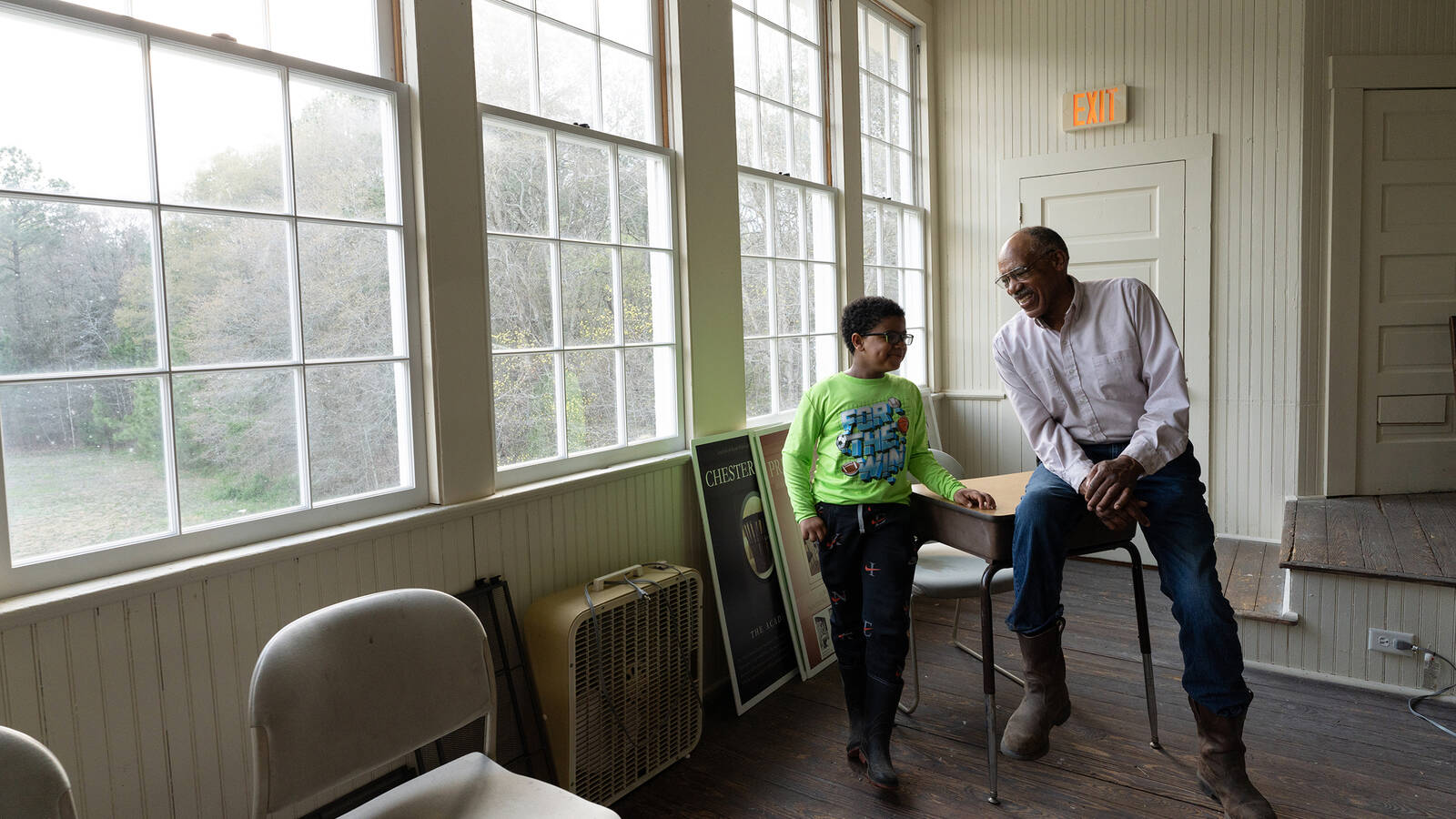

Newell Quinton and his grandson, Zana Kone, in the San Domingo School in

Maryland, which Quinton, his siblings and his parents attended.

Rudolph and Sylvia Stanley, accompanied by members of their family, stand in front of the San Domingo School. The couple, who have been married for 51 years, attended the school as children.

©ANDRÉ CHUNGNow, a group of preservationists, advocates, photographers, historians and civil rights activists are endeavoring to make sure the whole country knows about Rosenwald. They are planning a national park site, based in Chicago, that would tell the story of Rosenwald’s life and philanthropy; in addition, several restored schoolhouses in the South would become part of the park to highlight the schools and what they meant to Black communities desperate for education. Only about 500 Rosenwald schools are still standing, and of those, fewer than half have been restored so far. Historical trusts in many Southern states have inventoried the remaining properties and encouraged their preservation; many supporters believe that a national park designation will help with that effort. Down the road, the National Park Service could consider adding newly restored schools to the proposed park, or those buildings could possibly become complementary state sites.

If a Rosenwald historical park is ultimately designated, it will become the first national park site honoring a Jewish American. And it would introduce many Americans, including former Rosenwald school students, to a man whose name they had not known.

“He was a modest man. He didn’t want his name on the buildings,” said longtime NPCA volunteer and former board member Dorothy Canter, who first proposed the park seven years ago and is now president of the campaign to establish a Julius Rosenwald and Rosenwald Schools National Historical Park. “But he embodied social justice. He just wanted to give back. And he did. It’s a great American story.”

Separate and Unequal

In many ways, Washington and Rosenwald were opposites: an enslaved man turned scholar who believed education was a path out of poverty, and a fastidious son of the garment trade who became fabulously wealthy despite never finishing high school. But for both, their religious faith propelled their interest in social change. Washington believed Christ wanted to lift his people up. Rosenwald believed in tzedakah, or the moral obligation to do what is just, and thought that Jewish citizens, themselves persecuted in Europe, should help their Black brethren who suffered under the yoke of segregation. He was passionate about the Jewish value of tikkun olam, meaning “repair the world.” The day in 1911 that Washington and Rosenwald met was, according to Robert Moton, Washington’s Tuskegee successor, “a fortunate day for black people.” Many scholars agree.

Trailblazers Julius Rosenwald (left) and Booker T. Washington walk the grounds of

the Tuskegee Institute in 1915.

“This idea of these two men from different backgrounds coming together was an early form of social innovation in philanthropy and education,” said Brent Leggs, a Rosenwald scholar and the executive director of the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund. “The Rosenwald schools stand as a physical manifestation of a social movement in response to a crisis in Black education.”

During slavery, many Southern states had laws on the books prohibiting Black children from attending school or even learning to read, with penalties ranging from fines, flogging or imprisonment for white teachers and, typically, physical punishment for enslaved people. After the Civil War, though, these states began allowing Black schools and even supporting them through collected taxes. Many white residents complained; they saw no need for Black people to have an education, and they didn’t think their tax money should subsidize the schools.

“Education would spoil a good plow hand,” an Alabama state legislator, J.L.M. Curry, declared in a speech to the General Assembly in 1889. Three years later, the state passed legislation that essentially starved Black public schools of funds. Other Southern states struggled with the push-pull between a need to support Black schools (along with other institutions) just enough to keep their labor force from heading north but not so much that Black citizens began demanding more rights. Clarity arrived in 1896 when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson, ruling that “separate but equal” accommodations were to be the law of the land. The case was about railcars, but the precedent soon applied to all aspects of Southern life, including public schools. School segregation became systemic in the South, a part of life seldom questioned, according to Douglas A. Blackmon, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “Slavery by Another Name,” which details the convict slavery system — and other forms of forced labor — that emerged after Reconstruction.

“White people totally accepted the logic that there was no need for Black schools to be the equivalent of white schools,” Blackmon said. “The idea that there was any kind of legal, moral or practical need to provide equal educational opportunities had never crossed the minds of the vast majority of white Southerners before the 1950s.”

Meeting of the Minds

Washington had fought to attend school in the tiny West Virginia salt-furnace and coal town where his mother moved after the Civil War. He eventually was accepted at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, a prestigious Black boarding school in Virginia. Later, Hampton’s trustees helped him found the Tuskegee Institute, one of the nation’s first Black colleges. While traveling through the South to raise money for Tuskegee, Washington noticed the deplorable condition of Black schools, which were deteriorating even further in the wake of Plessy v. Ferguson. He wanted schools in rural areas to not just teach writing and reading, but also farming, gardening and life skills. He sought to prepare students to thrive under a segregated system by being dedicated to work and excelling at it. (Even at the time, other Black scholars and activists bristled at Washington’s accommodationist approach and willingness to work within the system, however unfair it was. In particular, the prominent scholar, W.E.B. Du Bois, while a supporter of Rosenwald schools, pushed for more. He wanted Black people to be as welcome in the opera houses as they were in the factories — and favored confronting and dismantling the system.)

Rosenwald, meanwhile, had outgrown his modest Midwestern roots, and his life transformed further when he took an ownership stake in Sears, Roebuck and Co. and turned that company into a mail-order powerhouse that offered satisfaction or money back. He began spreading his wealth around Chicago, giving to his synagogue, Jewish causes and YMCAs.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Rosenwald read Washington’s autobiography, “Up From Slavery,” after the investment banker, Paul J. Sachs, sent him a copy in 1910. Impressed, Rosenwald hosted a luncheon the following year when Washington traveled to Chicago to speak. Soon after, Rosenwald agreed to serve on Tuskegee’s board.

Rosenwald’s sojourns to Alabama for meetings proved transformative. He saw the way Black children lived in the rural South and found the segregation shocking and appalling. He became more keenly aware of a type of racism that he knew existed but had not witnessed in Chicago. Rosenwald recoiled at such hatred, thinking of his own people’s persecution in the pogroms of Europe. He wanted to be part of uplifting the Black community.

When Washington suggested a partnership to build schools, Rosenwald agreed, provided that the communities and the school boards become partners in the endeavor. He’d donate seed money, but the community needed to supply labor, land and materials, as well as some funds, and the boards of education would have to cover teacher salaries and other essential costs. The matching funds approach would become a new way of giving money away that reinvented philanthropy and is still popular today.

They began with six schools in Alabama. Tuskegee staff members designed the first ones, with touches that would make the schools recognizable architectural gems decades later. The buildings had walls of windows that let in natural light and could be opened in warm weather, and large cloakrooms where children could hang coats they wore on long walks to school. Retractable walls let the schools double as meeting spaces for community groups that often lacked places to gather. Many had kitchens in the back for cooks to prepare food and stoves like the one Quinton remembered for heat.

The two men were not far into their plans when Washington died in 1915, but Rosenwald forged ahead on his own. He continued to work with Tuskegee graduates and Robert Robinson Taylor, the first Black graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who had designed many of Tuskegee’s buildings. Fletcher Bascom Dresslar at the George Peabody College of Teachers in Nashville subsequently updated the designs.

Thanks to clean and well-lit spaces for learning, devoted teachers, involved parents and strong, supportive communities, the Rosenwald school students thrived. Families contributed resources, manpower and capital; elders frequently showed up at fundraisers with bags of pennies. That commitment and investment helped incubate leaders, and many Rosenwald students ended up at the vanguard of social justice movements. The late Congressman John Lewis, the revered civil rights leader, attended a Rosenwald school, as did Maya Angelou, Medgar Evers and Carlotta Walls LaNier, one of the Little Rock Nine who integrated Central High School in 1957. “My father would pray all the time that his kids had a better life than he did,” Quinton recalled. “And my mom would say, ‘You’re as good as anybody else.’”

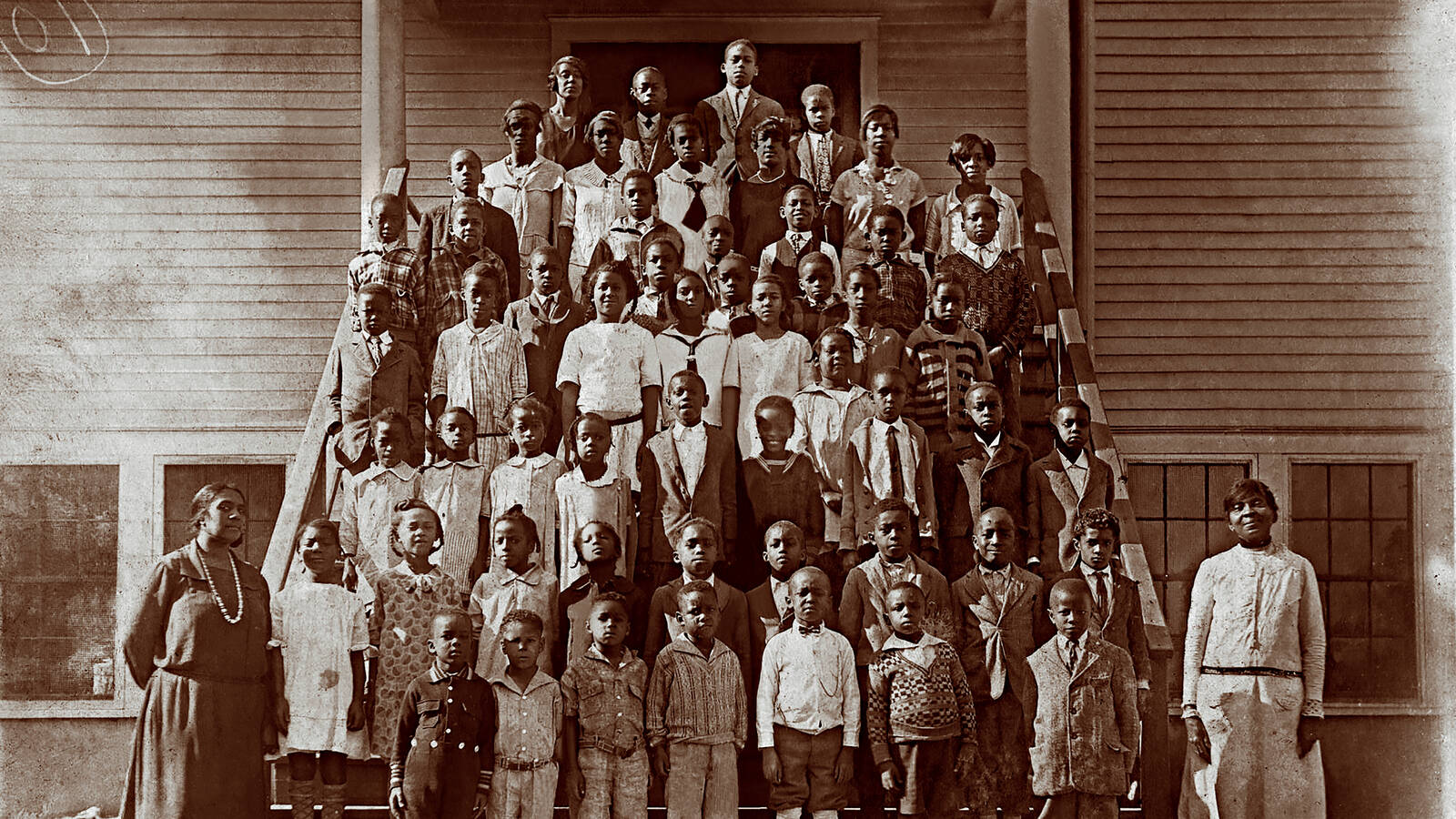

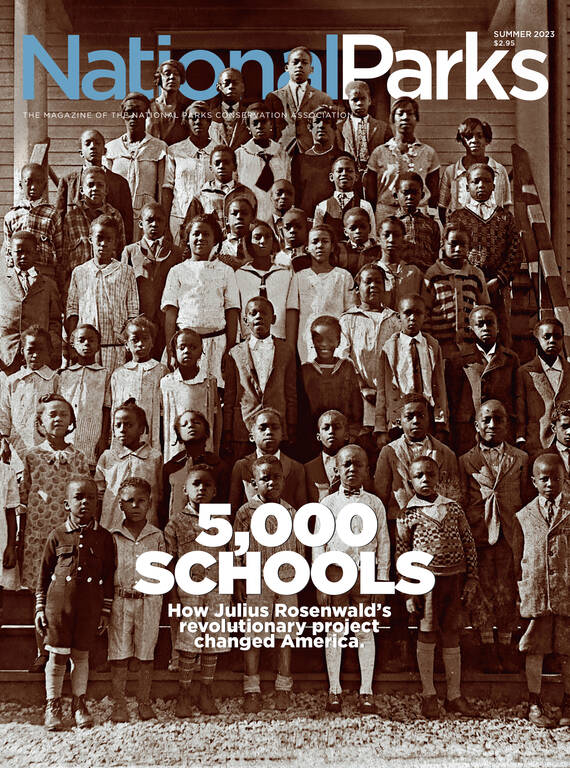

Students pose in front of the Jefferson Jacob School in Prospect, Kentucky, circa 1920. Roughly one-third of all Black children in the South passed through Rosenwald classrooms during the time the schools were active.

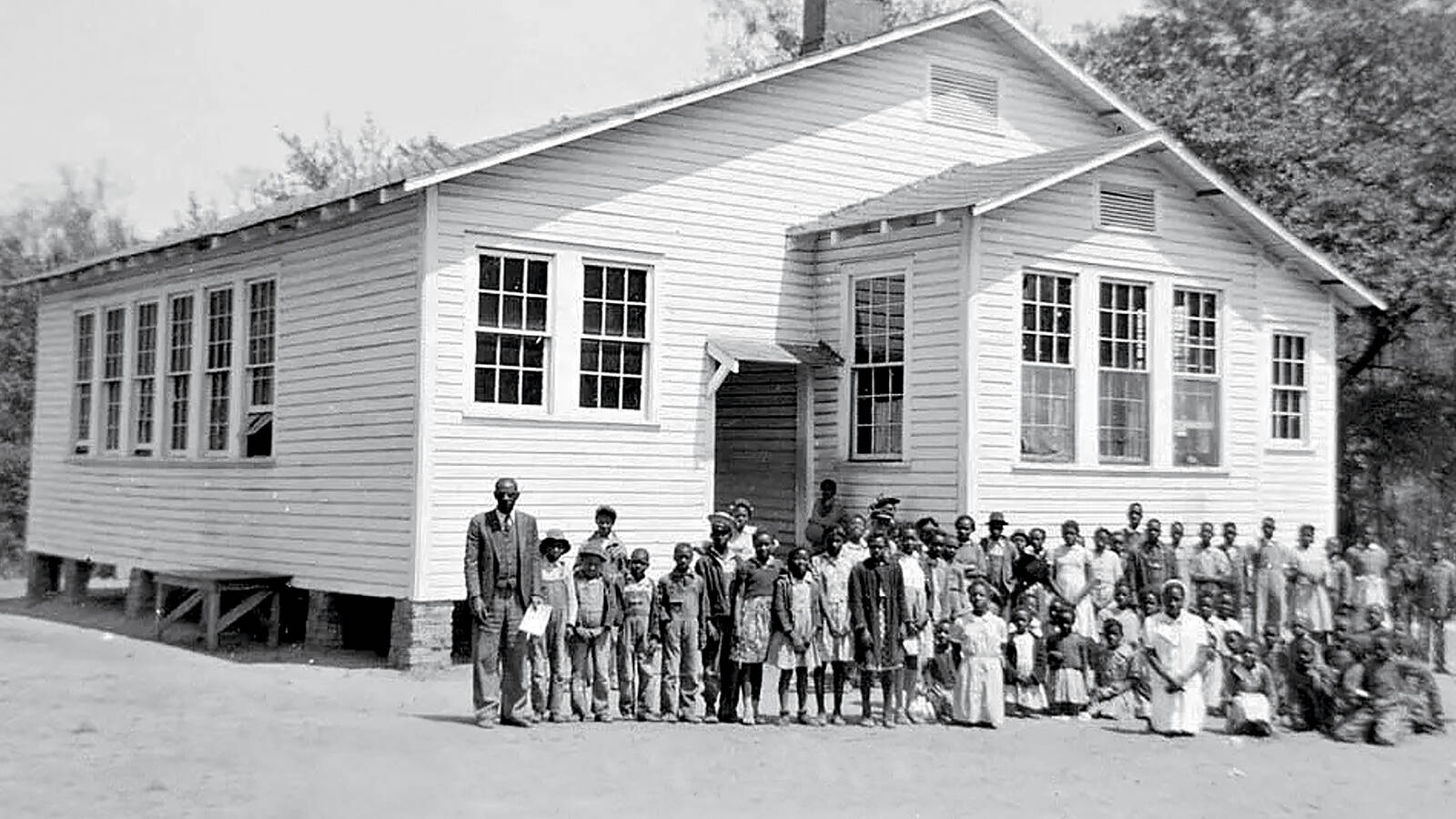

CARRIDDER JONES PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION, FILSON HISTORICAL SOCIETYStudents gather in front of the Pee Dee Rosenwald Colored School (as it was then called) in South Carolina.

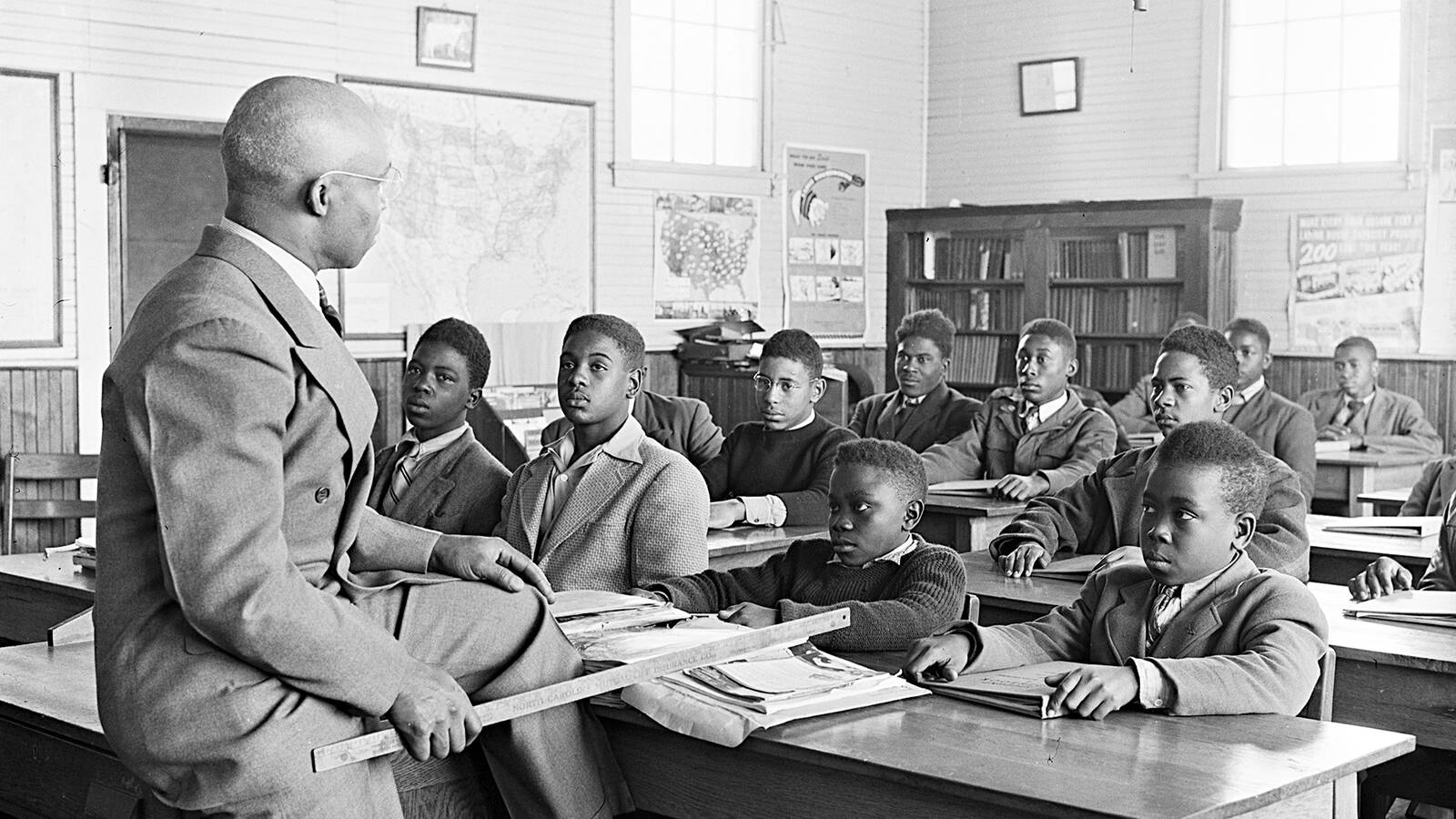

S.C. DEPARTMENT OF ARCHIVES AND HISTORYSingleton C. Anderson teaches a class of young men in a Rosenwald school in North Carolina.

HANNA HOLBORN GRAY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS RESEARCH CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LIBRARYStudents pose with Rosenwald at the Tuskegee Institute.

FISK UNIVERSITY, JOHN HOPE AND AURELIA E. FRANKLIN LIBRARY AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS/THE CIESLA FOUNDATIONA Legacy Almost Lost

Rosenwald wasn’t the only Northern philanthropist building schools for Black children in the rural South, but no one would match his drive, his efficiency or his ability to do so much so quickly, Blackmon said. “He had enough wealth to do things on an unprecedented scale.”

When Rosenwald died in 1932 at 69, Jewish and Black communities mourned the loss along with political leaders. “The death of Julius Rosenwald, which occurred in Chicago today, deprives the country of an outstanding citizen,” said then-President Herbert Hoover. In an interview in The New York Times several days after Rosenwald’s death, social worker and philanthropist Jacob Billikopf said, “One shudders to think what would have been the present state of race relations had not these 5,000 beacons of light shone through the years.”

In Judaism, a high form of tzedakah is to give anonymously. Rosenwald’s gifts were not exactly anonymous, but he was not like his contemporaries — Carnegie, Frick and Ford — who affixed their names to museums and libraries as conditions of their gifts. Most Rosenwald schools, such as the Sharptown Colored School, later known as San Domingo School, had names the community gave them. Rosenwald arranged for his eponymous foundation, which funded various projects including the schools and fellowships for Black artists and scholars, to shut down within 25 years of his death. In 1948, it closed as planned, having given away the equivalent of around $800 million in today’s dollars.

A Rosenwald school in Alabama shows signs of neglect.

COURTESY OF DAVID BULIT/ABANDONED ATLAS FOUNDATION“More good can be accomplished by expending funds as trustees find opportunities for constructive work than by storing large sums of money for long periods of time,” Rosenwald wrote in an article published in 1929. “Coming generations can be relied upon to provide for their own needs as they arise.” Eventually, progress would put the Rosenwald schools out of business. After Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, the American education system began its slow march to integration. In rural areas, that meant Black children often took buses to formerly white-only schools. By the late 1970s, most of the Rosenwald schoolhouses were no longer in use as schools. And though Rosenwald had required the schools to be built on high ground, climate change and sea-level rise had shifted the topography. Some ended up in marshland and were unsuitable to be rehabilitated. Others were repurposed, neglected or misused. One in the Shenandoah Valley became a county dump.

The decline continued until 2002, when the National Trust for Historic Preservation included all the Rosenwald schools on its list of endangered places. That spurred several states to take a closer look. Leggs, then a graduate student at the University of Kentucky, took on a project chronicling the condition of the schools in his state. Through research, he learned that both his parents went to a Rosenwald school. And he was devastated to subsequently find out that the school was gone, no more than an empty field. The discovery crushed and haunted him, and inspired him to change his career path to focus on the preservation of Black history.

“When we lose the Rosenwald schools, we are losing part of the American story,” Leggs said. “We are losing these physical testimonies that can inspire contemporary social movements. We are losing our tangible connection to the past that is related to our individual and shared identity. We are losing memories of children walking to school and toward their ambition and potential. And we are losing it because the traditional preservation movement did not prioritize this piece of American history.”

Stephanie Deutsch wrote “You Need A Schoolhouse,” a book about the partnership between Rosenwald and Washington. Her husband, David Deutsch, is Rosenwald’s great-grandson.

©ANDRÉ CHUNGSeveral of Rosenwald’s descendants followed in his footsteps, becoming activists and philanthropists, and Rosenwald’s grandson, Peter Ascoli, wrote the definitive biography of his grandfather. But the link to Rosenwald and his emphasis on tikkun olam faded with time. With the flexibility that their generational wealth provided, and the distance from pogroms and anti-Semitism, many Rosenwald heirs turned to secular pursuits. Some grandchildren married out of the Jewish faith, left Chicago and assimilated. Their children had an even more attenuated connection to their Jewish roots, their altruistic ancestor and his civil rights legacy.

“I grew up knowing nothing about Julius Rosenwald. Absolutely nothing,” recalled David Deutsch, a retired TV director who is Rosenwald’s great-grandson. “I didn’t even know I was Jewish until I was probably 11.”

His father, Richard Deutsch, married a nominally Episcopalian woman from the South, and they raised their family in Greenwich, Connecticut. David Deutsch knew the cousins on his mother’s side, but not on his father’s. But by the time his wife, Stephanie Deutsch, wrote, “You Need A Schoolhouse,” a book about the partnership between Rosenwald and Washington, David had begun connecting with his cousins, and the book changed his relationship to his family’s history.

“Just because you have money doesn’t mean you have a propensity for philanthropy,” said David Deutsch, who lives in Washington, D.C. “To give your money away because you think you are making a better world … to have that as an anchor, that’s unique. And it’s really been this wonderful, unexpected feeling, learning about all this, and meeting people who are so dedicated to their schools.”

A Chance Encounter at the Movies

One day in 2015, Dorothy Canter went to the movies with her husband. By chance, the Aviva Kempner documentary, “Rosenwald,” was showing on the big screen. It told the story of Rosenwald, his relationship to Washington and the schools they built together. Canter was “blown away” by Rosenwald’s work and surprised by the fact that she’d never heard of him. She immediately thought of an idea to honor him.

“I knew nothing about Julius Rosenwald, but I knew a lot about national parks,” she said. “I knew that there is not one national park unit that commemorates the life and legacy of a Jewish American.”

Canter convened a meeting with Leggs, Tom Cassidy from the National Trust for Historic Preservation and Alan Spears, NPCA’s senior director of cultural resources. They set up an advisory board (including Stephanie Deutsch, whom Canter met through a friend), crafted a plan and launched a campaign to establish a national park. The group asked each state to recommend schools to be considered for inclusion in the park. Fourteen states submitted 55 Rosenwald schools and one teacher’s house. The Julius Rosenwald and the Rosenwald Schools Act of 2020, which could pave the way for a national park, authorized the Department of the Interior to study sites associated with Rosenwald; it lists 10 schools, including Quinton’s in Sharptown.

Create a National Park Site Preserving the Legacy of Julius Rosenwald

A Julius Rosenwald and Rosenwald Schools National Historical Park would recognize an important legacy of philanthropy and social justice and be the first national park honoring a Jewish American.

See more ›The idea for a Julius Rosenwald and Rosenwald Schools National Historical Park enjoys bipartisan backing and has a list of nearly 200 supporting organizations, including synagogues, churches, Black heritage museums, foundations and Rosenwald schools support groups.

“This is not about glorifying Julius Rosenwald. This is about celebrating the work he did in conjunction with Black communities,” Stephanie Deutsch said. “It reinforces this feeling that this is a story we all share.”

San Domingo’s Legacy

Quinton’s parents only went to school through the fourth grade. After that, they had to work. His mother canned tomatoes; his father worked as a custodian. They pushed for a better life for their children, and the children’s teachers reinforced that push for excellence. Every day had a rhythm. Enter the school, take seats, recite the Pledge of Allegiance and devotions, and sing a song. In some classrooms, they had to stand for cleanliness inspections. Ears, underarms, hands. Fail, and it would be embarrassing. Lunch was a packed bag from home, with fresh milk from the milkman. Teachers only allowed outdoor recess if children had finished their work. Outside, softball and dodgeball were the most popular games, but too much misbehavior resulted in a cloakroom paddling.

“It was not just teaching us our ABCs,” Quinton said. “It was teaching us how to survive in a segregated society. We just felt that they did everything they could do for us in order to ensure we were successful. The teachers I experienced, it was not just their occupation, it was their life.”

Newell Quinton outside the San Domingo School, which he has labored to restore.

©ANDRÉ CHUNGThat dedication paid off, as many graduates from the school went into education, medicine and ministry. Seven of the eight Quinton children attended Morgan State University in Baltimore, a historically Black university, coming home in summers to pick vegetables for 10 hours a day, starting at 75 cents an hour, until some found better jobs on campus.

While at Morgan State, Quinton and his sisters Alma Catherine Quinton Hackett and Barbara A. Quinton joined protesters at Northwood Theatre, where managers refused to let in Black patrons. Baltimore police arrested Quinton’s sisters and took them to jail. The judge demanded a high bail, and neither the young women nor the NAACP could pay it. Some of their white friends at Goucher College, then all women, heard about the arrests and conspired to get arrested, too. The Goucher women reasoned their parents wouldn’t stand for them getting locked in jail, and the warden would have to let out the Morgan State students too. The plan worked, Hackett recalled with a laugh.

When Quinton began researching the school and told his siblings and cousins about Rosenwald, they’d never heard of him, either. But they were delighted that Quinton, whom they fondly call the family drill sergeant, took up the restoration cause.

“My life started here,” said Rudolph Stanley, 74, a cousin, as he admired the light coming through the windows on a recent visit to San Domingo School. He was there with his wife of 51 years, Sylvia, also an alumna.

“It’s a sense of pride,” added Hackett. “Here I am 80 years old, and I can sit in this classroom where I got my foundation and just reflect.”

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER

As they spoke, Quinton strode around the room, finally folding his lanky frame into a chair to reminisce. His freckled face lighting up as he joked with his siblings and told stories, Quinton stressed the values the school instilled. Respect. Remember whose son you are. For him, the resurrected school honors not just Rosenwald and Washington, but also those elders — the fathers and grandfathers who cut the timber for the building and the mothers and grandmothers who sold baked goods, hot meals and hand-sewn clothes to help raise the money.

“It represents so much of the sacrifice made by people that I just heard about through my parents,” Quinton said. “I’m always in awe of how they were able to do so much with so little.”

About the author

-

Rona Kobell Author

Rona Kobell AuthorRona Kobell, a frequent National Parks magazine contributor, is the co-founder of the Environmental Justice Journalism Initiative. She is also a professor of journalism and has written about the Chesapeake Bay for 20 years. Reach her at rona@ejji.org.