Winter 2023

Blazes and Colors

The 1947 fire ravaged Acadia National Park — and transformed the park’s autumnal display.

Thick-limbed oak, beech and maple trees towered over my wife, Chrissy, and me, as we pedaled along a carriage road in Acadia National Park a few days after Labor Day. A scattering of crimson leaves danced across the gravel, foreshadowing the brilliant colors that would appear in the coming weeks.

The red, yellow and orange fall foliage seems like quintessential Acadia, so it’s hard to fathom that the trees that put on such a glorious display every year have not always been so prevalent. In large part, the deciduous trees are growing here courtesy of a wildfire that burned much of the park just 75 years ago.

Mount Desert Island, where most of the park is located, is generally cool and damp, even in the summer. High temperatures rarely crest 80 degrees. Annual precipitation typically measures more than 50 inches, and locals joke that the month of “Fogust” falls between July and September.

But in the late summer of 1947, the island was fog free, hot and achingly dry due to a drought that extended across New England. Throughout the Northeast, fire danger was raised to the highest level, and fire lookout towers, typically shut down in early September, were reopened.

The blaze that ravaged Mount Desert Island started on October 17 near a dump outside of Bar Harbor, the island’s hub for park visitors, but no one knows for sure what caused it. Bar Harbor’s fire department responded minutes after the first call came in. Acadia’s firefighters soon joined the effort, and over the next three days, the crews confined the fire to 169 acres of dry marsh grass and kept it out of the nearby forests.

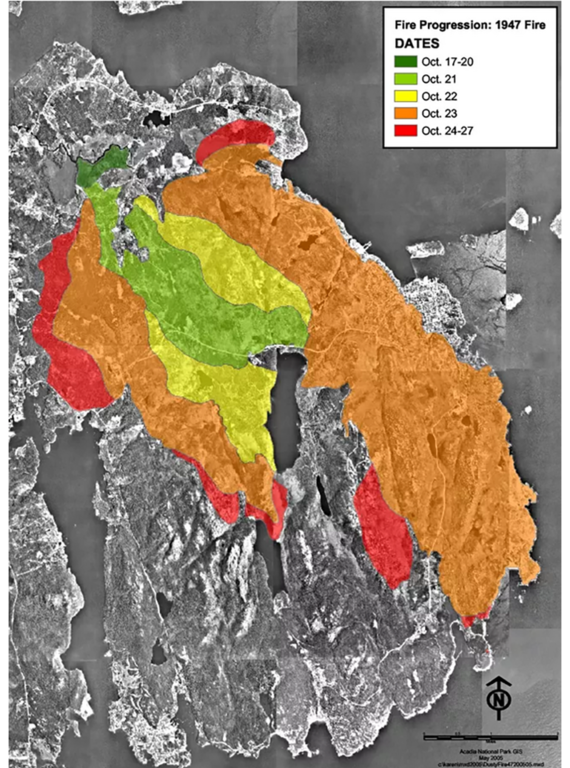

A map documenting the fire’s rapid spread over the course of a week.

NPSThen in the early morning of the 21st, the still-smoldering grasses flamed up again, fueled by fresh winds. The revived blaze swept north and south into timbered hills. By afternoon, the southern front jumped Eagle Lake Road and entered Acadia. The flames spread into the crowns of trees and threw out embers that started more spot fires, and soon the woods along the western shore of Eagle Lake were ablaze.

For the next two days, shifting winds drove the two fronts in one direction then another and another, complicating the task of fire crews, aided by local and federal reinforcements, as they battled the flames in Acadia and private lands north of the park. On the afternoon of the 23rd, a dry cold front ushered in gale-force winds that made the fire even more intense. The violent gusts pushed one front down Millionaires’ Row — a stretch of Gilded Age mansions outside of town — and directly toward Bar Harbor. As the flames raced toward town, 2,500 residents fled to the athletic fields just south of Bar Harbor. “It was an awful scramble — women running through smoke with household goods and crying babies in their arms,” a resident told an Associated Press reporter.

For a few hours, all roads out of town were closed off by the flames, and hundreds of people fled to the municipal pier where boats ferried them to safety as the sea foamed with whitecaps. When the road north was finally bulldozed clear, the remaining 2,000 residents piled into a caravan of 700 cars, buses and military trucks. Those in the open-air trucks covered themselves with wet blankets and tarps for protection from the falling embers.

It was an awful scramble — women running through smoke with household goods and crying babies in their arms.

Meanwhile, the southern arm of the fire tore through Acadia, scorching the eastern side of Cadillac Mountain, the Bubbles and several other peaks, before pushing all the way to the ocean at Great Head. “It was a bad dream, a terrific nightmare,” firefighter William Sheldon Jr. said in an interview with United Press. “It was enough to drive anyone out of their minds.”

Finally, on the 24th, the winds subsided. It took three more days to bring the stubborn blaze under control, though it wasn’t officially declared out until November 14, four weeks after it first started.

When the evacuees returned, the scene was devastating. The fire burned more than 17,000 acres across Mount Desert Island and Acadia. Most of Acadia’s iconic structures — including the popular Jordan Pond House restaurant — as well as Bar Harbor’s business district survived, but 67 of Millionaires’ Row’s grand estates, along with five historic hotels and 170 other Bar Harbor-area homes, were destroyed.

Survivors of the 1947 fire share their memories.

Only five people died in the Mount Desert Island fire. A military officer and a young girl died from injuries sustained in a car accident during the harrowing flight out of town, and an elderly man, last seen running into the basement of his burning home to rescue his cat, never came back out. Two other residents, already ill, died from heart attacks. In the coming years, 1947 became known as “The Year Maine Burned.” All told, over 200,000 acres of the state burned that fall, and 16 people died.

Today, the fire’s impact is etched across Acadia, even if blackened snags have long since disappeared. The stately hardwood forests that cover much of the park’s eastern core weren’t nearly as widespread before the fire. Back then, thick groves of conifer trees — spruce, balsam fir and eastern white pine — dominated most of Acadia. After the fire cleared the conifers and allowed sunlight to reach the ground, beech, oak, aspen and maple were able to take root and proliferate. But new generations of shade-tolerant conifers now grow toward the leafy spread above them. In the coming centuries, they’ll likely take over the park again.

For their part, Acadia officials aren’t terribly concerned about another conflagration like the one in 1947. The day before our bike ride, I met with Jesse Wheeler, the park’s vegetation program manager, and Kate Miller, a National Park Service forest ecologist.

According to Miller, 1947’s severe drought was an anomaly, as was the stand-replacing fire it fueled. The Wabanaki didn’t really use fire here as so many Indigenous Tribes did across North America, she explained. In Maine’s damp coastal forests, up to 1,000 years would pass between large fire events. “Our primary disturbance regimes are winter storms, wind events and insect infestations, not fire,” she said.

THE CCC IMPACT

Because the likelihood of severe fire is so low, Acadia doesn’t actively manage ladder fuel — downed trees, shrubs and other low-hanging vegetation — to reduce the risk. “Fuels management could actually be detrimental to our ecological management goals,” Miller said, further explaining that when a June 2021 storm dumped several inches of rain in just 24 hours, erosion was far worse in places lacking downed wood to slow the torrents of water.

Even climate change isn’t expected to cause another extreme drought anytime soon. Climate forecasts for this region do point to warmer temperatures in the peak summer months, but also to more rain in the spring and winter.

Of course, this doesn’t mean park staff aren’t taking the threat of fire seriously. “Even though we get fog all summer and the relative humidity stays high, our fire program monitors the moisture of the soil and downed wood regularly,” Wheeler said before ticking off all the other work the park does to be ready should a blaze ever blow up: a regularly updated fire management plan, consistent communication with local fire departments, recurring training for the park’s wildland firefighting crew and fire-safety education for park visitors.

And if a fire ever breaks out, it would be put out as quickly as possible. “We are a full-suppression park,” Wheeler said.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›The next day, as Chrissy and I biked on the carriage roads, something Miller had said popped into my mind: “Fires do have ecological benefits, so even if a fire did happen, it wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing,” she told me.

I tried to reconcile her comment with the dramatic accounts I read from people who lived through the 1947 fire — people whose homes were destroyed, whose relatives died and whose lives were upended. But at the same time, private land, scorched by the blaze, was donated to the park. Forests of deciduous trees sprang from the devastation, and new hotels now welcome hordes of leaf peepers each fall, a boon to a tourist-dependent economy. It’s a complicated legacy, one I struggled to assess as Chrissy pulled ahead.

Pedaling was easier than ruminating, so I shifted gears and accelerated to catch up to Chrissy.

About the author

-

Greg M. Peters Contributor

Greg M. Peters ContributorGreg M. Peters writes from Missoula, Montana, where he finds plenty of adventures just dealing with regular life. Find his work at www.gregmpeters.com.