Winter 2022

Out with the Old, In with the New

A generation ago, thousands of people gathered in a remote corner of New Mexico to usher in a gentler, kinder age. Did it work?

The sun rose bright and clear on our last day in hell. Its rays warmed the faces of scores of people camped in the desert way out west of Santa Fe to greet the arrival of the New Age. As the horizon brightened, someone in the crowd banged a gong, and the drummers picked up their tempo. Chants, flutes, rattles, bells and the occasional shriek echoed off the canyon walls. “Tears stream down my face; I feel like my heart is opening,” wrote one worshipper named Yakmiella Britton afterward. “The dawn of August 16, 1987, is here.”

Britton was among a few thousand people who’d made their way to Chaco Culture National Historical Park in northern New Mexico 34 years ago to join in a collective spiritual event known as the Harmonic Convergence. They — and tens of thousands of others around the world — answered the call of an author and self-described visionary named José Argüelles, who urged people to gather at sacred sites for two days of prayer, dance and meditation that would elevate Earth’s consciousness and facilitate our eventual communion with a galactic intelligence.

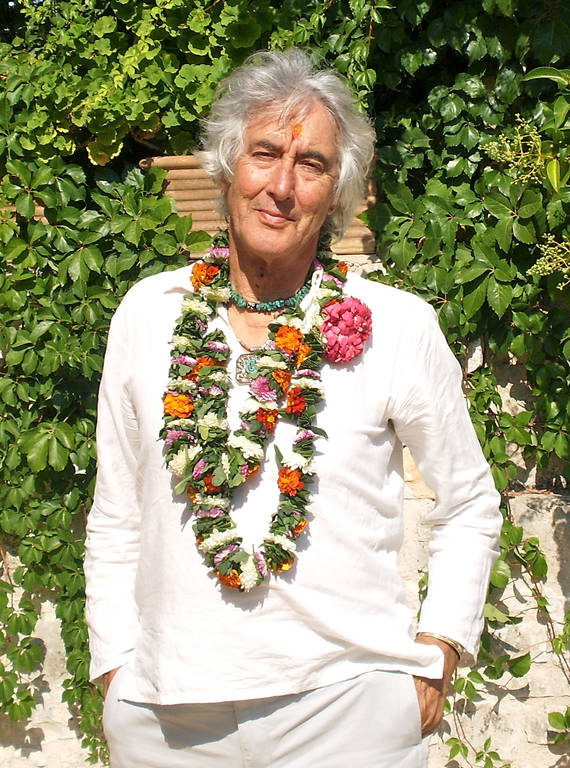

José Argüelles a few years before he died in 2011.

WIKIMEDIA COMMONSArgüelles reckoned that Aug. 16 and 17, 1987, marked a confluence of several portentous astrological events: It was the end of the final “hell cycle” of the ancient Aztec calendar, and the start of the final 25-year phase of the 5,125-year Mayan calendar. As Argüelles wrote in a 1987 book, the long cycle’s end, scheduled for 2012, would present participants with the opportunity to transform themselves into “cosmic resonators” and see to it that “the Armageddon script is short-circuited, yet the possibility of a New Heaven and New Earth is fully present.”

Got all that?

For a little help with translation, I called up Adrian Ivakhiv, a scholar of environmental thought and culture at the University of Vermont who has researched the Harmonic Convergence and its cultural roots. In Argüelles’ writings, Ivakhiv hears crisp echoes of Cold War anxieties and the fracturing of the 1960s counterculture. “By the 1980s, New Age spirituality emerges as this individualized version of what used to be a more radical social movement,” Ivakhiv said. The threat of nuclear annihilation still loomed large, and global warming was just starting to make headlines. In response, Ivakhiv said, the New Age movement expanded to fit “people who were looking to the future, to a more ascended, cosmic status for humans — and on the other hand, those who were more interested in what’s around here, and how people have lived in tune with nature for millennia.”

Among the dozens of gatherings staged at “power points” worldwide that weekend, including at the pyramids of Giza in Egypt, Uluru in Australia and Haleakalā National Park on Maui, Chaco Canyon occupied a spiritual sweet spot for skygazers and Earth worshippers alike. The park preserves dozens of intricate stone structures built between 850 and 1150 by the Chacoans, a people that 20 modern-day tribes claim as their ancestors. Many of these buildings are aligned to the cardinal directions and solar cycles. “There’s a powerful energy at Chaco,” said Charles Bensinger, a videographer and author who helped organize the 1987 gathering. “The Harmonic Convergence was a way for people to commune with the spirits and to reassert their deep, natural connections with Gaia.”

In the weeks leading up to the gathering, Bensinger and a dozen fellow Argüelles adherents set up shop in a conference room in Santa Fe and turned their focus to the earthly details of this cosmic gathering. The park is 70 miles from the nearest small town, and at the time, it sat at the intersection of three rough dirt roads, with limited parking and a single small campground bereft of shade and potable water. So Bensinger’s group met with staff from the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management to establish a campsite outside the canyon that would accommodate thousands of people. They rented port-a-potties, tents and shuttle buses; they arranged for waste management, first responders, guest check-in and traffic control. “We thought we were divinely destined to pilot this ship, to set it off on a voyage of planetary transformation, and make sure everyone got on board and got to their destination,” Bensinger said.

Meanwhile, descendants of Chaco Canyon’s ancient architects were, at best, nonplussed by their ancestral land’s role in this drama: The chair of the Hopi Tribe told the Los Angeles Times that the tribe was “officially distancing itself from the event.” Park staff too might have wished the universe had elected a less remote and delicate point in which to concentrate its power. Nevertheless, then-Superintendent Tom Vaughan took up the challenges of ensuring public safety, protecting the park’s fragile environment and archaeological sites, and upholding the First Amendment. “Others might have looked down their noses at the crystal gazers and feather wavers and so on, but these people have a constitutional right to their own spiritual needs,” said Vaughan recently. (Still, to be on the safe side, Vaughan’s supervisor also ordered in five SWAT teams for the weekend.)

Starting on Aug. 15, a steady stream of cars started turning off the highway and rolling into camp. The weekend’s ceremonial center was the great kiva Casa Rinconada, a circular, open-air chamber sunk into the floor of Chaco Canyon. People from various faith traditions staged all kinds of ceremonies within and around the structure throughout the weekend. “It was a powerful thing, meditating with people inside the kiva,” Bensinger recalled. “You could almost feel the vortex of energy swirling around, descending deep into the earth and up into the heavens.”

After three days of vigorous spiritual exercise, the Convergers dispersed. Only time would tell if they’d managed to stave off Armageddon, but in dozens of letters to the organizers in the weeks after the event, attendees reported an array of more immediate side effects. “My psychic sense is much more acute and accurate,” wrote one participant. “I now sense the meaning of life on this planet in a continuum-evolutionary,” said another. (Bensinger published these letters in his 1988 book, “Chaco Journey: Remembrance and Awakening.”)

You could almost feel the vortex of energy swirling around, descending deep into the earth and up into the heavens.

If the gathering at Chaco Canyon left a lasting impression on its participants, they would also leave their own mark on the park. The event inaugurated an era of intense interest in Chaco Canyon among New Age practitioners. To this day, park staff occasionally collect and catalog crystals, handcrafts and other offerings left by worshippers, said Wendy Bustard, Chaco’s longtime curator, who retired in 2020. And throughout the decade following the Harmonic Convergence, New Agers frequently staged smaller ceremonies, drums and all, within Casa Rinconada.

The ongoing use of the ancient kiva for these rituals didn’t always sit well with park staff, other visitors or representatives of the 26 tribes — including Pueblo Nations, Hopi, Navajo, Ute and Apache — the Park Service has formally consulted about Chaco Canyon since 1990. Bustard said the uptick in foot traffic and the occasional burying of offerings risked damaging the archaeological integrity of the kiva. What’s more, several of the Pueblo and tribal representatives she worked with “just found it maddening that Anglos with no ritual knowledge of this landscape were using these sites to make up religious rites,” she said.

“The language is ours,” said the late Peter Pino, administrator for the Zia Pueblo, in an interview in 1997. “The songs and traditions and dances are ours. When people appropriate them, it’s exploitation of intellectual and cultural property.” The same year, the Park Service closed Casa Rinconada to all visitors, taking into account the wishes of many Indigenous people who trace their lineages back to the culture that produced the extraordinary structure a thousand years ago.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›In 2011, just a year shy of the transition he foretold, Argüelles died at age 72. His followers are left to wonder whether their efforts in 1987 found their target. More than three decades later, the coronavirus has killed 5 million people worldwide, and Cold War angst over nuclear annihilation has given way to contemporary dread about the climate crisis. And no reasonable person could scroll through Twitter and conclude that ours is a particularly enlightened or harmonious age. “Gee whiz, we had all these great visions of a near future we thought we were ushering the planet into. Violence, poverty, inequity and all these things would vanish miraculously,” Bensinger said. “All that didn’t happen, obviously. So were we deluding ourselves?”

And yet, for Bensinger and his fellow Convergers, schlepping out to the desert to participate in what was probably history’s first global meditation festival was nothing if not an act of faith — a faith Bensinger hasn’t lost even if the view through the windshield looks grim. “It’s hard for me to say anything specific about how the Harmonic Convergence is impacting our present reality,” he mused. “But I’m sure it’s playing a role somehow.”

About the author

-

Julia Busiek Author

Julia Busiek AuthorJulia Busiek is a writer living in Oakland. She's worked in national parks in Washington, Hawaii, Colorado and California.