Fall 2021

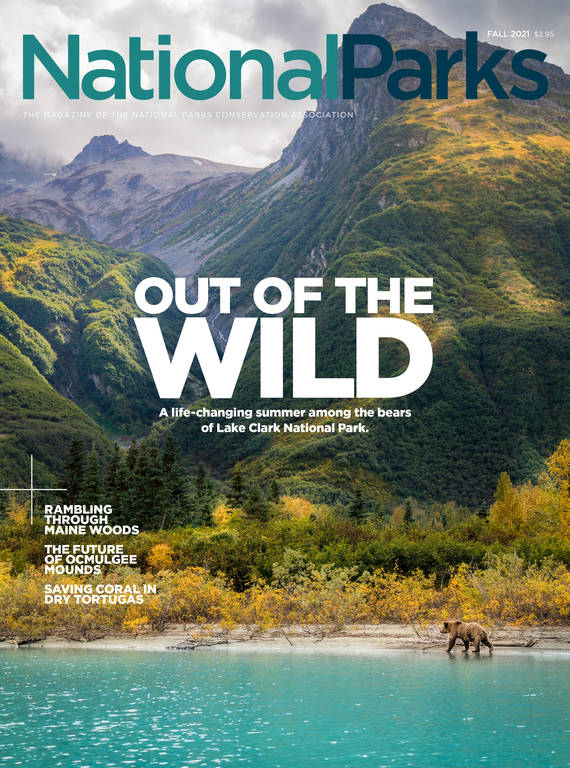

Out of the Wild

A life-changing summer among the bears of Lake Clark National Park and Preserve.

I used to have nice dreams about bears.

When I was in my late teens, I’d dream of grizzlies roaming over lawns and munching on grass in my suburban neighborhood in western New York. At the time, I never quite understood why I’d have these dreams, but I’d wake up exhilarated. I felt drawn to Alaska as if by some unbending law of physics. At age 22, I drove to Alaska to work for a summer cleaning rooms with the idea of seeking real bears and real wilderness.

I saw both, and, year after year, I returned to Alaska to work as a guide or ranger, which managed to keep my bear dreams at bay. But in the spring of 2017, when I was 33, the dreams returned, except this time the bears would be chasing and/or eating me. I’d wake up damp with sweat, wondering if it had been a good idea to accept a job at Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, where I was to spend a summer living amid one of the world’s densest populations of brown bears.

Established in 1980, Lake Clark is one of the country’s least-known and least-visited national parks. Its 4 million acres — located 120 miles southwest of Anchorage along the Cook Inlet coast — are middling by Alaskan park standards, but Lake Clark is bigger than Connecticut or any of the lower 48 national parks. There’s far more to it than its size or namesake lake: nearly two dozen rivers, creeping glaciers, dense boreal forest, and the mountains of the Alaskan and Aleutian ranges that soar as high as the 10,197-foot Redoubt Volcano. Lake Clark contains numerous significant ancestral sites of the Dena’ina people, who have lived in the area for thousands of years. Tribal members continue to fish and hunt in the park in accordance with legislation that allows for subsistence use of federal lands.

The region is also home to bears. Lots of bears. Many of North America’s 55,000 brown bears live on the Alaska Peninsula — the 500-mile saber that slices through the Pacific. (Brown bears and grizzlies are the same species, though it is customary in the area to call the larger, coastal creatures “brown bears” and the smaller, inland ones “grizzlies.”) The coastal bears are so large because of their diet made up of sedge grass high in protein, razor clams as big as hot dog buns and abundant salmon.

As a ranger, I was to monitor human-bear interactions on a 3-mile section of coast within the park boundaries. I wouldn’t be out there alone. In this part of the park, known as Silver Salmon Creek, there are a few private cabins and two private lodges that employ guides who accompany guests on walks up to bears. Bush planes from outfits based in Anchorage, Homer, Kenai and Soldotna also land on this stretch of beach every day in the summer. Because of the large number of visiting groups and commercial operators, the Park Service erected a log cabin some years back and started employing park rangers to live there during summers.

I had been looking for a way to escape an untenable living situation, support my writing career and also hit a reset button. The gig seemed like it might do all three, so I went for it, accepting my responsibilities with a kind of reckless “I’ll probably get through this despite being unqualified” derring-do. For the past decade, that’s how I’d been approaching my life, which was in a constant state of improvisational flux and opportunistic movement. I was often living out of a vehicle or packing a summer’s worth of belongings into a backpack. I had a driver’s license from Nebraska, health insurance in North Carolina and family in western New York.

Although I’d worked at another park in Alaska, I didn’t have experience mediating group conflicts or dealing with bears. My training, in the village of Port Alsworth where Lake Clark’s field headquarters are located, included a refresher on shotguns and bear spray, and a chat with the park’s wildlife biologist. Because there weren’t any actual bears in the training, being flown out to a cabin surrounded by bears felt like being called in to perform heart surgery after reading a medical textbook.

The morning after the training ended, I loaded a small bush plane with as many boxes of food as I could (potatoes, cans of pineapple, Bob’s Red Mill muffin mix) and was flown to my cabin. We soared above the clear and placid Lake Clark — a narrow, 42-mile mirror that reflected the cloudy sky — then in between tall mountains, where impenetrable tangles of alder clung to steep slopes. Along the ocean coast, wet sand was etched by scores of squiggly streams, which stretched inland to the forested shore like long roots. When we passed over my home for the season, I could see the bulky bodies of a few brown bears in the light green sedge meadows near Silver Salmon Creek, a small inlet that widens with brackish water twice a day when the tides come in.

A ranger named Kara, who’d spent a couple summers living in the cabin, joined me for the first few days.

“Here, the bears are like dogs,” Kara said with a giggle, shortly after we arrived. “But don’t tell anyone I said that.” A little later, in a more serious tone, she explained that a couple of years back, a bear had attacked a tourist — an English lady who unfortunately got tossed around and whose foot was bitten. (She survived.) Kara also casually mentioned that some of these bears might like to eat a human, which had me wondering what sort of dogs Kara had been hanging out with.

In truth, brown bears, like most bears anywhere, pose little threat to responsible humans, but every year there are a handful of bear attacks. In the state of Alaska, between 2000 and 2017, there were 68 hospitalizations and 10 fatalities due to bear attacks. (To put these numbers into context, it should be noted that hunters kill somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 bears in Alaska each year year, on average — and that doesn’t include other human-caused bear deaths.)

Kara gave me a tour of my new home, the Silver Salmon Creek ranger cabin. Surrounded by tall Sitka spruce trees, the spacious log cabin has a big porch with a long roof overhang supported by three timber columns. Gutters that run along the roof — a shiny, metallic forest green — channel rainwater that is pumped from garbage bins to the kitchen sink. Inside are two bedrooms and a large living space with a table, couch and, tucked in the corner, a dried spruce sapling ornamented with fishhooks and spinners. Plus, there’s an oven and a fridge with a tiny freezer, both of which run on propane. A sauna, an outhouse and a storage shed (where I would keep a pile of chopped firewood for the cabin’s wood stove) sit in the backyard, a carpet of soft moss and rough lichen. It’s a two-minute walk to the creek or ocean coast. My initial thought: I can’t believe I’m getting paid to live here.

One of the first things I did was clean out the sauna, which a porcupine had invaded over the winter. I fired up the sauna’s wood stove, excited for a trial run, and left to do more chores as the sauna warmed up. When I came back in, I was hit by a wall of noxious smoke. Waving my arms and coughing through the smoke, I saw that I’d left a 5-gallon Home Depot bucket on the wood stove. Bright orange molten lava was dripping down the side of the stove and onto the floor. I spent the next three hours with a hammer and screwdriver chipping away at the plastic, now hard and glued to the stove, hoping that no one back in Port Alsworth would find out.

“Well that was a long shower,” Kara said, when I finally returned.

On my first morning on the job, I walked out to the beach to phone the Alaska Region Communications Center, which takes calls from rangers in the backcountry and notes that they’re still alive. As I was extending the satellite phone’s antenna, I watched a brown bear saunter toward me on the path I’d just walked. A small red fox daintily trotted next to the bear, as if they were buddies. I wasn’t sure if this was a scene from an innocent British picture book or from one of those old German fairy tales full of carnage and hard lessons learned. I took out my bear spray, uncapped it and prepared for discharge. This, I’d quickly learn, was an overreaction. Every day I’d see around 30 brown bears, and many would get much closer to me than this one.

Kara and I hopped on the all-terrain vehicle and drove farther down the beach. We walked over the tidal flat to join one of the local guides with his six tourists, who were snapping photos of a brown bear sow digging up razor clams. The tourists barely looked up at us, so fixated were they on photographing the bear scooping heaps of sand with her paw. With all six cameras clicking, it sounded like we were approaching a stage of Irish tap dancers.

I watched, mesmerized, as the bear, just 20 yards away, pulled a clam out of a hole and ever so delicately pried the shell open with its claws, before unceremoniously gobbling the clam’s pale body. This is the sort of intimate bear behavior many visitors come to see at Lake Clark and nearby Katmai National Park and Preserve. It’s a practical guarantee to spot a brown bear at a few select feeding spots, such as the salt marsh at Chinitna Bay in Lake Clark or Brooks Falls in Katmai, where visitors can watch brown bears catch salmon from an elevated platform. Because the bears must fish in close proximity to one another, they’ve learned to tolerate the presence of other creatures. This ability, and the fact that they are well fed by the bounties of land and water, make them relatively blasé about sightseeing humans.

Unlike Katmai, Lake Clark has no minimum distance requirement for bear viewing, so visitors at Silver Salmon Creek can theoretically get as close to bears as they reasonably can, especially on the beach, where the state has jurisdiction, not the Park Service. To protect both bears and visitors, Lake Clark published bear-viewing guidelines in 2003, in collaboration with commercial operators, Katmai National Park and the state of Alaska. But bear-viewing tourism has grown substantially over the last decade, and those recommendations are due for a review, said Megan Richotte, Lake Clark’s manager for interpretation. The park administration is in the beginning stages of updating the coastal management plan, she said, noting that the process involves working with stakeholders to develop strategies that balance visitor experience with the protection of park resources.

Meanwhile, the guides, some of whom have been conducting bear-viewing tours for years, have developed a loose set of rules that they all follow for the most part: Walk together in clusters, not lines; better to let the bear get closer to the group than vice versa; never allow multiple viewing groups to “wall off” a bear; make sure to communicate with other guides over walkie-talkies if you want to join a group “sitting” on a bear; never eat around bears. If these protocols are followed, the bears never have reason to become alarmed or conditioned to human food. Some of these bears had been photographed up close their whole lives. Later in the season, I’d watch a 1-year-old cub — already accustomed to the clusters of photographers who followed it around all day — get so close to a group that anyone could have scratched under its ears.

“We’re like walking trees to them,” the guide assured me that first day. “These bears don’t view us as a threat. At all.”

My first impression of this weird bear-human dynamic was that it was crazy and dangerous and unnecessary and that I wanted nothing to do with it. But the human mind has an incredible skill for adaptation. Within minutes, I was there alongside the tourists — our little walking forest — snapping photos and feeling as if this was all perfectly ordinary.

Kara left, and my solitary life began to take shape. I was unbothered by many of the daily nuisances of modern working life. I didn’t wake to an alarm, endure a mind-numbing commute, or have supervisors looking over my shoulder. My workdays began and ended whenever I liked. I’d make oatmeal and tea for breakfast, and then hop on my ATV and join a few bear-viewing groups on the beach or sedge prairie. I wrote down plane numbers, listened to the guides gripe about one another, and fell in love with every passably attractive guest. I tended my four jars of sprouts that were blooming into a curled mess on the windowsill. I’d dig for clams at low tide or fish for Dolly Varden char or salmon in the creek. Sometimes I’d host a visiting field biologist, and while I always enjoyed their company, the introvert in me craved having the place all to myself again.

A lot of my time was spent maintaining my cabin. I trimmed weeds along the electric fence, rewired the water pump, painted the shed and chopped firewood. One of my favorite duties was building a wheelchair-friendly, 25-yard gravel path to the creek. Every day, I’d take my ATV and trailer down to the beach, shovel in a load of gravel, haul it back and then lay the rocks over a mesh covering. It was good, exhausting work and the only visible evidence to anyone that I was doing anything.

I have park ranger friends who’ve told me about being verbally abused by anti-government cranks, but I’ve never experienced anything like that. The Park Service is arguably the most beloved agency of the federal government, and everyone seemed to warm to me as I gave my talk about the history of the park and the habits of bears. If there was a kid on board, the air taxis sometimes called me on my air-to-ground radio to ask me to meet the plane to deliver a junior ranger ceremony. Apparently somewhere in my training binder, I was given a junior ranger oath that the kids were supposed to recite. I never noticed it, so I’d improvise my own, asking the kids, with raised palms, to pledge to commit to everything from ecological restoration to soil rehabilitation. Sometimes I’d throw in something about climate change. Despite the occasionally controversial (and certainly over-serious) nature of my oaths, the parents always looked on proudly, and the kids repeated my words and accepted their small plastic badge with an almost tearful solemnity.

NPCA at Work on Alaska’s Bear Coast

When I wasn’t working, I’d sit on the front porch and gaze into the deep green of the woods, listening to the waves lap against the beach at high tide, the wind swoosh through the topmost spruce boughs and the chatter among the red squirrels. I sauteed razor clams in garlic and butter and baked salmon filets in the oven. I’d pull up my chair next to the wood stove and listen to a classic rock station, one of five stations available on a portable radio. I read “Pride and Prejudice,” a history of Scotland and almost all of the “Game of Thrones” books — and I felt it was easier to get lost in these worlds in my sanctuary of quiet. These are the good memories.

But other times I felt as if I was under the curl of a dark tide. I wasn’t sure what I should have been doing with my life. Living alone in a cabin and being employed at a seasonal job in my mid-30s — perhaps when I should have been making a family, finding a steadier source of income or developing the writing side of my career — made me question my life choices. No one knew my 34th birthday came and went. By the end of the third week, my summer’s worth of chocolate bars was gone.

I wish I could go back and tell my younger self: You’re doing fine. Be grateful to be in this beautiful place. Don’t spoil it with fretting over the future. Enjoy the fishing, identify a few new plants, read a few good books. But that’s the trouble with seasonal employment: You always need to be thinking four months ahead to line up your next job, your next home, your next friend’s driveway to park your car in. It’s hard to live in the today when you’re under pressure to figure out tomorrow.

My isolation was put on pause when my friend Paul flew from Buffalo, New York, for a weeklong visit. Paul had driven up to Alaska with me on that first trip 12 years earlier but hadn’t been back since then. He now worked at a cardboard factory. He was paid well, but he hated the midnight shift and found the work unfulfilling. A year before, his girlfriend of eight years, for whom he’d bought an engagement ring, cheated on him and left him with a Dear John letter. He was still emerging from the wreckage.

We went on a 23-mile hike along the coast, carrying an 8-pound portable electric fence. Paul comes from an expressive Italian-Irish family, so the emotional range he brought to our expedition was a good complement to my stoic temperament. I shouldered every burden silently while Paul loudly moaned about every bruise, scrape, bump or rash. The flip side was that Paul, when in a good mood, would constantly express awe about the scenery, the animals and the adventure. I was happy he was there.

After our first day of walking, our feet were rubbed raw by sand that had crept into our socks. We took a break and followed a creek into the woods, which led to a lagoon of cold water, slick rocks and long quiet sloughs packed with fish. Sun shafts broke through the forest, shining light through the clear water on schools of silvery fish. We’d happened upon an enchanted lagoon, a fisherman’s dream, and it felt all the more special knowing how few people on the planet knew about this place.

I’d been trying and failing to catch a fish for weeks, and now I could clearly see at least 50. We spent an hour or two getting bites. We waded through the lagoon to pull out stuck lures. We fought and lost epic battles. Finally, I watched Paul muscle in a 15-pound monster. Seeing the wild delight on his face during a low point in his life made me inexpressibly happy. Later, as we cooked the fish over a driftwood fire on the beach, Paul said, “For all my life, I’ll never forget this.”

Many of us who feel stuck in cities or suburbs have some symbol of wilderness that reminds us that there’s another existence out there — one that, maybe just maybe, we’ll get to live. Paul was determined to see a wolf on this trip. For Paul, the wolf represented a simpler way of life: a sensory-based existence spent in the open air, not one stuck inside the cold corners of a factory. For me, back in my late teens, it had been the grizzly bear. I’d thought of the grizzly as not just an apex predator, but as apex wilderness — the wildest, most ferocious, most dangerous embodiment of the natural world. And I used to think that to get close to one would be to confirm that, yes, I had finally made it into true wilderness.

Paul needed wilderness for escape, for revival. I once needed this, too. I believe I used to have recurring dreams of grizzlies because something within me was nudging me to get out of the suburbs and find adventure and truth in the depths of wilderness someplace far away. In waking life, I imagined that Alaska could possibly connect me to ancient sensations, to a core self. I may have been propelled by the exuberance of youthful romanticizing, but I do think the Arctic mountains I’d scrambled up and the close encounters I’d had with wild animals made previously terrifying things — job interviews, speaking in public, talking to women — slightly less terrifying. Wilderness can be not only a portal to the past, but a portal to a wilder, better version of you.

But I no longer needed solitude or transformation. I was living the way my younger self had wanted to, but I wasn’t that young man anymore. The improvisational nature of my life, which once had felt enlightened and deliberate, now felt disorienting and, in jobs like this one, unnecessarily risky.

And I no longer felt mystically drawn to bears. Especially after my many encounters that summer. Rarely did bears so much as look at me, but there were a few close calls. One cranky bear clicked its jaws at me as we walked past each other on the beach. An adolescent bear approached me as I fished off the coast until I screamed it away. Another used a horizontal fence post to step over the electric fence encircling my cabin and rubbed its back against a timber column on my porch, waking me from a nap. I was rarely terrified, but I was always in a state of hyper-vigilance. I missed going on carefree walks and jogs. I grew tired of the low-level fear I always had humming in the background of my mind, the steady drip, drip of cortisol in my bloodstream.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was walking in circles. Without knowing how to get to the next stage of life, I was falling back on my established work patterns and crisscrossing the country following the rutted paths of my old range. My constant state of movement was its own form of stasis.

I was tired of missing friends’ weddings. Of making close friends at seasonal jobs and never talking to them again. Of having my nose stuck in a book in some forgotten corner of the Earth. My malaise wasn’t so much due to the place, but my foreignness to it and the solitary circumstances I found myself in. Unlike the Alaska Natives who have lived in the region for millennia, I wasn’t surrounded by family, friends and fellow tribal members. This wasn’t home, and I wasn’t sure where home was.

As fall approached, the weather got windier and rainier, and the planes stopped landing on the beach. The sedge grew tough and stalky, the salmon run ended, and the bears moved into the woods and hills as they prepared for hibernation. I found myself feeling something worse than fear or loneliness — nothing. I started to live more in the stories of my books than the reality around me.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›That summer in Lake Clark National Park, I went into the wilderness, and the wilderness told me to leave. Sometimes the right journey isn’t to venture into the wild, but out of it.

When the season ended, I drew up a list of all the towns in America I might like to start a new life in. I didn’t know anybody in some cities. Other cities appeared to be made up entirely of unwalkable urban sprawl. All seemed unaffordable. Ultimately, I bought a one-way flight to Scotland, with the idea of roaming a new continent and maybe starting a new life.

On that trip, I met my future wife at a book festival. We now live in a small suburban house in a quiet village. I have a kid, a mortgage and a driveway of our own to park our car. In my 20s, I’d never imagined living in such a place, but, at present, it feels right.

Sometimes I hike the Highlands of Scotland, where there hasn’t been a wild bear for over a thousand years. It’s nice not to have to constantly worry about bears invading my tent at night. I feel safe, but sometimes when I look over these bare, empty hills, I feel like they are missing something. That I’m missing something. Perhaps it’s that which makes the land come to life. That which makes an ecosystem seem healthy and whole. That which can haunt nightmares, enchant dreams, inspire feelings of wildness and freedom, or summon uncertainty and terror. Bears beckoned me one decade and scared me away the next. And, who knows, one day they just might call me back again.

About the author

-

Ken Ilgunas Contributor

Ken Ilgunas ContributorKen Ilgunas is the author of “Walden on Wheels,” “Trespassing Across America” and “This Land Is Our Land.” He lives in Scotland.