Spring 2019

What is going to happen to national parks in the next century?

We asked a handful of writers, activists, scholars and conservationists about their hopes, dreams and fears about the National Park System. Here’s what they had to say.

AN AMERICAN STORY

By Carolyn Finney

Carolyn Finney.

© MICHAEL ESTRADAI love stories. When asked to share my feelings about the National Park System, my first impulse is always to tell a story. While there are a number that come to mind, I tend to tell one about my father and our visit to Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park in 2005. I was living in Atlanta at the time and had been interviewing African Americans around the country about their diverse environmental experiences. What did the great outdoors mean to them? I was working out how to weave those stories into my dissertation when my parents visited. It was the perfect excuse to step away from my computer and head to the nearby site, which gives voice to the black experience during the 1950s and ’60s.

The park sits in downtown Atlanta on a busy street where you can find Ebenezer Baptist church, the house King grew up in and the visitor center, where we began our visit. As my parents and I walked into the building, we were immediately hit with the sights and sounds of the civil rights era; images of protests, advertisements and news stories were accompanied by the sounds of King’s voice coming over a loudspeaker. We felt the exhibit before thinking about it, and we let our senses lead the way. My mother wandered off as my father and I stood in front of a set of photographs.

Now, my father, then 74, is not an effusive man when it comes to his feelings (unless he is angry), so I was surprised when he suddenly grabbed my arm and a look of panic and fear crossed his face. He actually grew a bit pale, and I thought he might be having a heart attack. But before I could fully react, he giggled (also very uncharacteristic), then pointed to a photograph in front of us. It was a black-and-white image of a sign that read “For Whites Only.”

“I saw that sign and for a moment I thought we weren’t supposed to be here,” he said. I realized he was grabbing me to get me to safety. I was stunned.

That’s not the end of the story. We found my mother and joined a tour of King’s childhood home. The young ranger leading the tour had serious storytelling skills, and we were all enthralled, not least of all my father. At the end of the day, after we left the park and went to dinner, my father said that he couldn’t believe he’d had such a good time at the park! He went on about it, which was so uncustomary for him, I began to wonder if there was something extra in the iced tea we were drinking. But what I’ve come to realize is that he had a good time because the story told at the park was also his story — the joy and the pain of being a black man living in America during the ’50s and ’60s was something he carried with him. And to see it acknowledged, shared and valued was a way of recognizing and honoring his experience. It also opened the door to healing.

My dream of how the National Park System might evolve over the next 100 years is really a dream about how we might evolve. How we might be in better relationship with this Earth and each other. How we will uncover and recover stories of who we’ve been and who we could be. And how we will continue to share those pieces of our history, no matter how hard they might be to tell. It’s those untold narratives, in particular, that give us a chance at redemption while allowing original ideas to emerge. And the national parks — places of beauty, pain, the past and the present — are the most valuable repositories of our country’s stories that we have. May we continue to treat these spaces with the care, love and respect they deserve.

CAROLYN FINNEY is a writer, performer and cultural geographer. She is the author of “Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors” and served on the National Park System Advisory Board before resigning in 2018 with 10 of the board’s 12 members to protest Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke’s unwillingness to meet with them.

Terry Tempest Williams.

© KWAKU ALSTONA 22ND-CENTURY PARK

By Terry Tempest Williams

Canyonlands National Park — It is 2155; the Colorado River is now an ephemeral river that runs only in the spring due to the aridification of the American Southwest. Drought is too kind of a word for where we are now.

Canyonlands National Park has been left alone and remains a geologic park, though it’s accessible only by enclosed viewing stations at Island in the Sky and the Needles Overlook that are cooled by solar power. It is too hot to descend into the canyons below. Travel by car or bus is prohibited. The roads are closed, historical scars reminiscent of a time when the world was fueled by gasoline and people drove cars without thinking. The relentless heat has buckled and cracked the pavement. Entry by foot is rare, though some remaining Desert Mothers and Fathers make their yearly pilgrimages to Druid Arch at their own peril, driven by the force of their religious convictions.

Virtual-reality glasses are provided at the lookout stations where hearty visitors, many of whom knew these erosional parks as children or from the cherished photographs of their ancestors, come to remember when these red-rock landscapes were places of inspiration and a desert ecology blossomed each year. No longer; the land can’t support much life at all. The glasses repopulate the barren landscape with the plants and animals that once lived in this high desert: sage, chamisa, blackbrush, brittlebush, globe mallow, primrose, yucca, prickly pear and willows. Cottonwood trees redrawn along the mighty Colorado draw gasps. Ringtail cats, mountain lions and mule deer also inspire awe.

Canyonlands National Park.

© EUNICE EUNJIN OHWhen they lower the glasses, visitors can still spot ravens (tricksters that they are) in the red-rock chasms lifted up by afternoon thermals. A few reptiles — collared lizards, whiptails and rattlesnakes among them — also remain, surviving on scattered insects. The rattlesnakes’ dry desert rattles can now be heard more as a haunting than a warning.

Canyonlands is staffed by robots who have been programmed to tell the geologic story of the park and the life that once flourished here. Donned in gray and green uniforms and stiff brim hats, they look like their human counterparts of past decades. The difference is they can withstand the extreme temperatures — well above 120 degrees Fahrenheit — and do not need the water now rationed among the few residents who manage to live nearby.

“There have been two great exoduses in the Colorado Plateau,” the robot says, “one in the Holocene, led by the pre-Puebloan people, and the other in the Anthropocene, which is occurring now. Climate refugees are retreating not only from the rising seas on the East and West coasts of the United States of America but from the rising heat in the Desert Southwest. America’s National Relocation Parks scattered throughout the Midwest and Great Lakes region are sites for internal migration as the Great Escape continues. In this new era of Climate Conformation, we are learning to adapt to the conditions we once denied.”

The national park robot turns to the visitors, saying, “I invite you to step outside briefly and feel the burning beauty uninhabitable now to most species.”

TERRY TEMPEST WILLIAMS is the award-winning author of 15 books, and her writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Orion Magazine and elsewhere. She is writer-in-residence at the Harvard Divinity School. Her most recent book is “The Hour of Land: A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks”; “Erosion: Essays of Undoing” will be published in October 2019 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Farabee in February 1977, sitting on a bag of marijuana that he and other Park Service employees dove to recover from a backcountry Yosemite lake after a plane loaded with thousands of pounds of the drug crashed in the park.

COURTESY OF BUTCH FARABEETELLING THEIR OWN STORIES

By Butch Farabee

In October 1969, a small team of law enforcement officers arrested the Charles Manson, the cult leader, in a forsaken Death Valley ranch house. Several park rangers had led the way to Manson’s hiding place in a bathroom cabinet; for days, two of those rangers — Dick Powell and Don Carney — had been doggedly pursing imprecise clues left in a remote part of the park by the now infamous criminal. An absorbing story, it is one you do not hear much about. And that, dear readers, is the crux of my grumbling.

No one documents our country’s cultural and natural history better than the National Park Service. The geologic timeline of the Grand Canyon. How and why Gen. George Custer died. The ancient history of Mesa Verde. The bravery of people on Flight 93. The agency is renowned worldwide for illuminating our collective heritage, but it tells its own story rather poorly.

There are so many little-known narratives like the one about Manson. Few are aware, for example, that when Hurricane Andrew ripped into the Bahamas, Louisiana and Florida in 1992, the Park Service activated its national All-Risk Management Team, led by Incident Commander Rick Gale, a park ranger. For three months, some 350 caring Park Service employees — scientists to crane operators — labored hard and long to clean, repair, rebuild and help the overwhelmed staff of Everglades and Biscayne National Parks deal with the devastation the storm had left in its wake. That collaboration was built around the incident command system, a new and innovative management tool that hadn’t been used on that scale previously and was subsequently adopted by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Or consider this: In 1993, Park Ranger Daryl Miller, enduring wind chill nearing minus 70 degrees, dangled from a rope 100 feet beneath Denali National Park’s helicopter. “Cowboy” Bill Ramsey, a pilot, had just deftly lifted Miller off the top of Mt. McKinley. Part of the preparation for the climbing season, it was the first time that an operation at that elevation — 20,320 feet — had ever been successfully undertaken. The training exercise paved the way for numerous mountain rescues that saved many lives.

The list goes on. Surveying the USS Arizona, the Park Service’s elite underwater ranger-archaeologists helped shed light on the sacrifices of the 1,177 sailors who died when the ship was bombed in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. More Department of the Interior Valor Awards have been earned by national park rangers than by employees at all other department agencies combined. Since Congress instructed those in Yellowstone to protect the forest from ax and fire in 1886, the agency has been at the forefront of wildland firefighting. For at least the past six decades, ranger teams have routinely been deployed to major events and incidents, such as the Exxon Valdez oil spill, presidential inaugurations, outlaw motorcycle gang rallies and undercover law enforcement sting operations involving thousands of irreplaceable Native American artifacts.

And this is just the tip of the ranger story. There are a great many ways that the Park Service’s scientists, archaeologists, wildlife experts, educators, managers and maintenance crews make a difference every day.

None of these contributions are intentionally kept secret or hidden, but they are often invisible. There are exceptions, of course, such as the Park Service’s documentation of its response to the September 11 attacks and the activities of the Civilian Conservation Corps of the 1930s, but such records are few and far between. I am not criticizing Park Service historians. They justifiably need to focus on telling the country’s stories and are outstanding at what they do, but they need help.

The roles of the men and women of the Park Service have expanded dramatically since Yellowstone was created in 1872. I hope that as the agency continues to evolve over the next 100 years, it will better recognize and more fully record the countless accomplishments of its own people who are making history … today.

BUTCH FARABEE retired in 1999 after a 35-year career in the Park Service. He worked his way up from laborer on a trail crew to park ranger to park superintendent.

Thomas Lovejoy.

COURTESY OF THOMAS LOVEJOYCONNECTING THE DOTS

By Thomas Lovejoy

When I was 8 years old, my attention was riveted by the national parks on the National Geographic globe that glowed in my bedroom. To me, the patches of green represented a promise of adventure. I was also convinced that they were safe havens for nature and wildlife.

Nowadays, we understand the situation is much more complicated. Parks are becoming isolated remnants in a fragmented natural landscape, and they’re vulnerable to outside forces, from agrochemicals that seep into park rivers to air pollutants that ignore park borders.

Climate change is the greatest threat of them all. As temperatures rise, for example, the range of Joshua trees will shift to the point that few may be left in Joshua Tree National Park. It raises the questions of where might we go a century hence to actually see these unusual trees and whether the park’s boundaries should be changed. In places such as Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, musk oxen are raising underweight calves because their winter forage is now often glazed with frozen rain instead of easily brushed aside snow. What will the management challenges and imperatives be in these landscapes that are in in flux?

In a landmark 2012 report, scientists took another look at the classic Leopold Report of 1963 written by A. Starker Leopold (wildlife management expert and son of conservationist Aldo Leopold). The main conclusion was — and is — pretty obvious: The management mandate needs to extend beyond the borders of existing parks to embrace the larger landscape in which they are set.

Because the geographical ranges of plant and animal species will shift, we will need to find ways to increase natural connectivity within landscapes. That can be challenging but is not impossible. For example, federal highway funds — through existing provisions — can be used to create underpasses and overpasses for wildlife.

Riparian vegetation also can help restore natural connectivity. For many species, it can provide natural cover and serve as corridors between habitats that can no longer support them and locations that will be favorable under a new climatic regime. We should take advantage of every possible opportunity to restore these sorts of natural connections.

It is my hope that the multiple impending changes in our environment will move people to think differently about their relationship to nature and the wonders of the national parks. If we collectively take the proactive measures necessary to assist in the survival of species, parks will no longer be isolated treasures set in the midst of human-dominated landscapes. Instead, we will have a vast natural web connecting these jewels we love so much.

THOMAS LOVEJOY is a professor of environmental science and policy at George Mason University and a senior fellow at the United Nations Foundation. He is one of the founders of conservation biology and introduced the term “biological diversity” in 1980.

Rahawa Haile.

© CHARLIE LOYDTHE FUTURE OF US

By Rahawa Haile

I grew up in Miami beside the sawgrass and cypresses of Everglades National Park. Most memories of my childhood are colored the same tannin hue of its waters and laced with fallen anhinga feathers. My family and I visited the famed river of grass year-round, kayaking and learning the histories of the Calusa, Tequesta and Miccosukee tribes while our bodies sustained constellations of mosquito bites and patches of sunburn. We loved it: the damp, unapologetic heat of the place, the sweat of its mangroved wilds.

I came to understand the vulnerabilities of the park after Hurricane Andrew tore through it in 1992 when I was 7. On the frontlines of climate change, South Florida faces extreme heat, damaging storms and sea-level rise. Those threats have collided with a long history of rampant development, water diversion and aquifer depletion, jeopardizing the health of the Everglades and the entire region. While restoration efforts are underway to improve the quality and flow of water into the park, it’s too late to repair much of the damage. Half of South Florida’s original wetland areas, which covered 11,000 square miles in the early 1800s, are simply gone; the number of wading birds, including roseate spoonbills, great egrets, white ibises, tricolored herons and snowy egrets, has also dropped precipitously.

Undeniably, the future of the remaining Everglades, as well as our other national parks, will be the future of us. The two are bound intrinsically, and not because our survival as a society depends on that of our most beloved natural spaces, but because our survival as a species is contingent on the circumstances that enable those places to thrive.

If the seas continue to rise, if the air and waters continue to warm, if the fires burn without end, if the rivers run dry, if the oceans further acidify, if vulnerable natural habitats are demolished for the sake of capital, if tribal lands are seized by extractive industries, if we create an environment that damns nonhuman life, we could bear witness, in this 21st century, to a catastrophic ecological and societal unfurling.

But salvation of the lands we love and the life within them is not unimaginable. The people we vote into power and the actions we take today will have consequences far beyond the present moment. My hope for the future of the Everglades and other threatened places is that we keep fighting for them — and by extension, for us — for as long as possible.

RAHAWA HAILE is an Eritrean American writer based in Oakland, California. Her work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, Outside, Audubon, Rolling Stone and AFAR. “In Open Country,” her memoir about thru-hiking the Appalachian Trail, is forthcoming from Harper Books. Find her on Twitter at @RahawaHaile.

Barbara Takei.

COURTESY OF BARBARA TAKEIFACING THE PAST

By Barbara Takei

In early 1970, I first searched for Tule Lake, the American concentration camp in Northern California where my mother, my grandparents, and seven aunts and uncles were incarcerated during World War II solely because of their Japanese ancestry. Tule Lake was one of 10 prison camps our government built to incarcerate 120,000 Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens.

Tule Lake was unique as the only one of the 10 camps to be converted to a maximum-security segregation center used to punish the 12,000 Japanese Americans who exercised their First Amendment rights by speaking out against their mistreatment. Tragically, those who protested were labeled as “troublemakers,” then stigmatized and shamed for most of their lifetimes by pervasive propaganda that such free speech was “disloyal.”

On my first visit, I saw little evidence of the once immense Tule Lake incarceration site where more than 27,000 Japanese Americans were treated with the dignity and consideration given to livestock. Records show 331 men, women and children died from various causes including inadequate medical care, government brutality, depression and suicide. After the war, homesteaders bulldozed the concentration camp’s cemetery and used the cemetery’s earth to fill ditches and build an airstrip. That airstrip occupies the majority of the area where our families lived.

Standing in front of a ragged barbed wire fence — decades later I learned it bordered the stockade where hundreds of imprisoned Japanese American dissidents were brutalized and tortured — I wondered what happened to more than 1,300 barrack buildings and the camp’s 28 guard towers. My inquiries to local residents produced mainly a racial slur: “Oh, that Jap camp?”

Over the decades, the Tule Lake Committee has worked to ensure this American site of shame would not be paved over and forgotten. In 2006, part of the Tule Lake Segregation Center was at last designated a national historic landmark, and the National Park Service began the process of validating and reintegrating the segregation center’s stories of dissent into the nation’s history. The thousands of protesters segregated to Tule Lake are finally being acknowledged for the moral and political courage that fueled their exercise of the fundamental right of free speech.

The Park Service has begun to preserve its part of the Tule Lake site and bring to light its history. Much of the site remains threatened by the proposed expansion of the rural airstrip that cuts through the middle of the concentration camp. Future preservation of Tule Lake will depend on Modoc County and the Federal Aviation Administration coming to recognize that it is an irreplaceable historic site, a place that reminds us of a time when the Constitution was nothing but a scrap of paper.

In considering the next 100 years, thanks to the advocacy work of organizations such as NPCA, I trust that desecration of this national human and civil rights treasure will be averted. It will take time and persistence, but Tule Lake will be one among a growing constellation of park sites that honor our nation’s racial and cultural heritage.

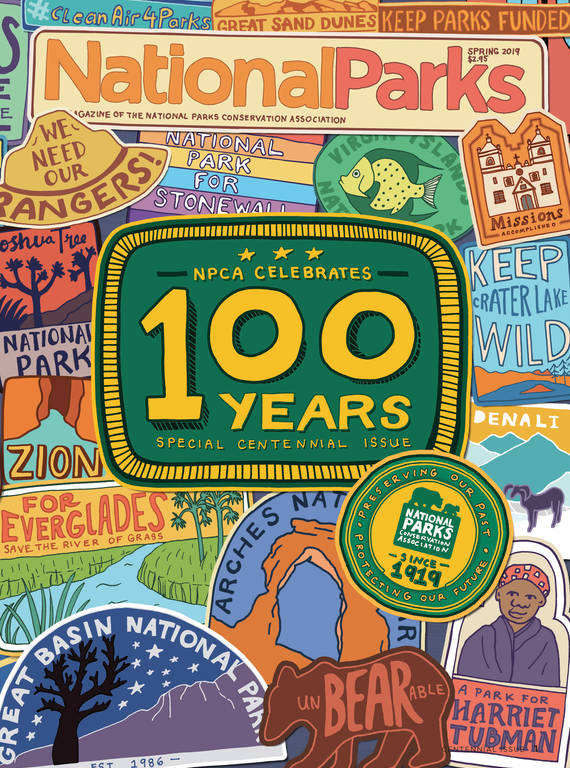

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Sadly, however, as I write, the nativism and xenophobia that led to the incarceration of my family and my community during WWII are resurfacing. Detention of innocent children and their families and the cynical use of fear and racism to service political opportunism are again shredding the ideals of American democracy. In such times, the national parks, the guardians of our nation’s history and stories, play a crucial role in educating visitors not only about America’s virtues and triumphs, but also about the shameful parts of its past. As we begin NPCA’s next 100 years, let us each vow to do what we can to keep alive the ideal of an America of liberty and justice for all.

BARBARA TAKEI serves as a board officer on the Tule Lake Committee and has researched Tule Lake’s history and advocated for the site’s preservation since 1999. She is the co-author of “Tule Lake Revisited, a Brief History and Guide to the Tule Lake Concentration Camp Site” and is currently working with historian Roger Daniels on “America’s Worst Concentration Camp” (University of Washington Press).