One famed photographer used his gift to protect the landscapes that gave him inspiration.

2016 marks not just one, but two centennials — that of the National Park Service and that of Ansel Adams’ first visit to Yosemite National Park.

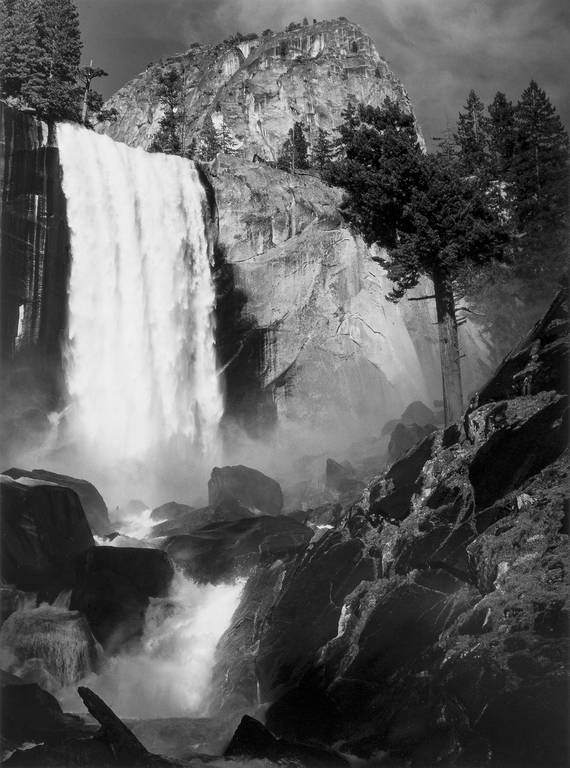

Vernal Fall, Yosemite Valley, California, circa 1948.

Photograph by Ansel Adams, ©2016 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights TrustOf his first sight of Yosemite, Adams recalled, “In the bright morning [we took] the grand, dusty, jolting ride in an open motor bus up the deepening, greening gorge to Yosemite. That first impression of the valley … was a culmination of experience so intense as to be almost painful. From that day in 1916, my life has been colored and modulated by the great earth gesture of the Sierra.”

His subject was the awe he felt in nature, the humbling exaltation he felt in the wilderness, whether manifest on a huge or tiny scale. In the early 1930s, other photographers and critics complained that the world was going to pieces while people like Adams and Edward Weston were photographing rocks. Adams responded in a letter to Weston that “Humanity needs the purely aesthetic just as much as it needs the purely material.”

He recognized that there was something he was suited to do for humanity, namely to share the beauty of wilderness and convince people to keep some areas inviolate for generations to come. He said he couldn’t make art about bread lines or unemployment lines — that wasn’t his ability — but he could inspire reverence and gratitude for nature.

He also became an activist for conservation. The Sierra Club sent him to Washington, D.C., in 1936 to lobby for a bill before Congress to create Kings Canyon National Park. He toted his portfolios from Senate to House, meeting with more than 40 members of Congress, telling his story of finding his life’s purpose in the parks. He spoke before a conference on the National Park Service and there met Harold Ickes, secretary of the Interior, and shared his photographs with him.

That 1936 bill failed, but Adams assembled his Kings Canyon images with others made in the Sierra and published them as a book, “Sierra Nevada: The John Muir Trail,” in 1938. He sent a copy to Secretary Ickes, who shared it with President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Kings Canyon National Park was created the following year, putting half a million acres under protection. Director of the National Park Service Arno Cammerer wrote to Adams that “A silent but most effective voice in the campaign was your own book … As long as that book is in existence, it will go on justifying the park.”

From 1940 on, Adams taught thousands of young photographers, many of whom went on to careers as nature photographers. In case you’re imagining a nightmare scenario of Adams judging pale imitation after pale imitation of his own well-known images, year after year, like the Saturday Night Live episode of Paul Simon dying and going to purgatory only to find it an elevator playing Muzak versions of his greatest hits, have no fear. Adams himself said “Most people have the idea that there is nothing you can do with a camera in Yosemite except take another postcard snapshot. I remind workshop participants that the national parks provide an experience, a mood, an incredible subject for the camera. The fact is that it happens in a national park and is stimulated by the photographer’s feeling that it is a new kind of scene, and this feeling is possible because Yosemite had been set aside and protected as a national park. But the beauty itself was there even before it was a national park.”

Stay On Top of News

Our email newsletter shares the latest on parks.

This is one way that the parks have continued to repay their debt to the art of photography, which has been essential to the conservation of wilderness areas from the first national parks to the most recent monuments at Mojave Trails, Sand to Snow and Castle Mountains.

This content was adapted from the lecture event Ansel Adams and Advocacy: An Evening with the National Parks Conservation Association, held earlier this year at the Reynolda House Museum of American Art in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

About the author

-

Phil Archer Director of Program and Interpretation at the Reynolda House Museum of American Art

Phil Archer Director of Program and Interpretation at the Reynolda House Museum of American ArtHe leads the museum’s exhibition and educational programs centered on American art and the history of the Reynolda estate. Throughout his 20-year tenure, he has skillfully and meaningfully found ways to bring to life the art, history, architecture and beauty of Reynolda. He curated the museum’s current exhibition “Grant Wood and the American Farm,” which runs through December 31, 2016.

-

General

-

- NPCA Region:

- Pacific

-

Issues