The National Park Service and its partners offer ways to honor the legacy of this scholar and pioneer who changed the way we understand American history.

Update: The Carter G. Woodson Home officially reopened in May 2017 and was offering tours prior to the pandemic. Learn more on the National Park Service website.

When Carter G. Woodson created the precursor to Black History Month in 1926, it was not just a novel educational concept—it was a groundbreaking initiative that shaped public thinking and inspired pride in African American achievements and culture during the Jim Crow era.

Woodson devoted his life to pioneering and popularizing the study of African American contributions to society, believing deeply that people without a sense of their own history are robbed of a measure of their self-worth and are more vulnerable to subjugation. In his words, “Those who have no record of what their forebears have accomplished lose the inspiration which comes from the teaching of biography and history.”

The Washington, D.C., home where Woodson founded what is now Black History Month and where he lived from 1922 until his death in 1950 has been part of the National Park System for ten years—but the building’s severe structural deficiencies have made it unsafe to open to the public.

“A lot of the home and adjacent structures were propped up with bracing. When those were removed, we found the walls weren’t as stable as we thought,” explained Ann Honious, deputy superintendent for National Capital Parks-East, the group of D.C.-area parks that includes the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site. The Park Service acquired the site’s three buildings—Woodson’s actual home and the adjacent row homes on either side of it—in February 2006, after they had stood unused for years. A 2011 earthquake made the already unstable structures even worse.

“We really don’t have a date right now as to when the work will be completed,” she said, noting that contractors have begun assessing the damage, but still need to determine which parts of the buildings must be stabilized and which must be entirely rebuilt.

Fortunately, part of the long-term plan for interpreting Woodson’s legacy includes strengthening not just the walls, but also the connections between his work and the accomplishments of two other area luminaries whose lives are commemorated by nearby historic sites—the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House and Frederick Douglass National Historic Sites. Park Service staff have been sharing Woodson’s story at these sites, even as his home remains under construction.

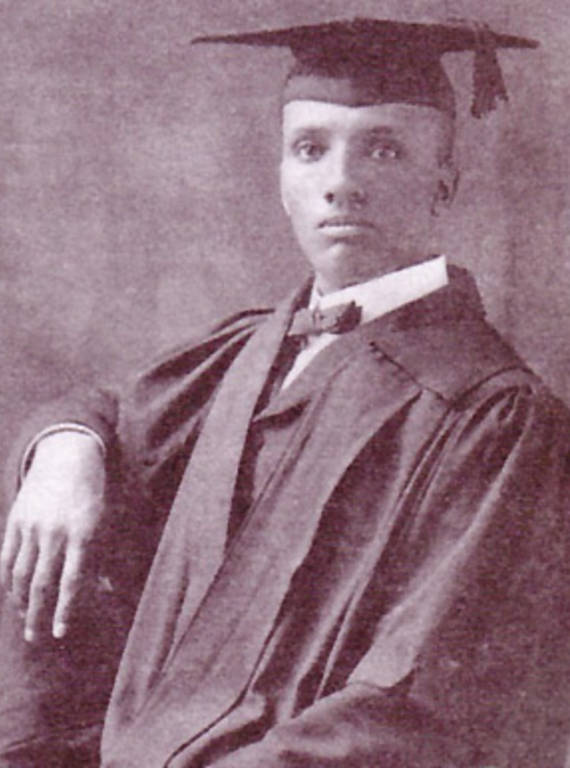

Carter G. Woodson rose from humble beginnings to become the second African American (after W.E.B. DuBois) to receive a PhD from Harvard University.

Photo courtesy of ASALH.“History is not static. It’s a continuum,” noted Kamal McClarin, museum curator and historian for National Capital Parks-East, who helps interpret the history that connects these three leaders. “A lot of groundbreaking research on Frederick Douglass was done by Woodson’s mentees,” he noted, adding that these mentees included such visionaries as Langston Hughes and Lorenzo Greene. Another noteworthy connection: Woodson designated February for celebrating African American history because it was the month when Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln both celebrated their birthdays.

Mary McLeod Bethune also served as an educational pioneer, championing schooling for African American girls and founding her own national civil rights organization, the National Council of Negro Women. She lived just a few blocks from Woodson and was a close friend, a regular lunch companion, and an important part of his circle of influence.

“What motivates me is the sheer tenacity and dedication that he had for not only discovering the African American past, but accurately writing about it and trying to bring that past into the forefront,” said McClarin about Woodson’s legacy. “He spent his whole life dedicated to that vision and that mission.”

Woodson came from humble beginnings. The son of formerly enslaved Americans, he grew up in West Virginia in a large, poor family and was unable to attend school for most of his childhood because his family needed his help on their farm. He taught himself basic reading and math skills and later worked as a coal miner until he could begin putting himself through high school at age 20. He went on to become the second African American to earn a PhD from Harvard University (after W.E.B. DuBois), and later served as a dean at Howard University and what is now West Virginia State University.

Woodson founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915 to help represent a fuller picture of America’s history and make that history accessible to all people, not just academics. He established a publishing company to print and distribute works by African Americans and other minorities—people whose ideas might not have otherwise received a wider audience. His work shaped not only how African Americans understood their own history, but also how whites understood the contributions of minorities in America.

His organization, now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), continues to launch educational outreach initiatives during Black History Month and the rest of the year—especially programs focused on youth. This year, ASALH is raising awareness around African American history in national parks as part of its “Hallowed Grounds” Black History Month theme in honor of the Park Service centennial.

It may not yet be possible to see the place where Woodson kept his office, walk among his books and artifacts, hear jazz from his music collection, or sit on the front stoop where he read aloud to neighborhood children. But ASALH continues to maintain resources on Woodson’s life and history and an extensive library of his publications. And the Park Service shares his story through exhibits and walking tours of his neighborhood at the Bethune House and a celebration of his birthday each December.

Woodson’s good friend Bethune may have encapsulated the significance of his work best when she said, “With the power of cumulative fact, he moved back the barriers and broadened our vision of the world and the world’s vision of us.”

About the author

-

Jennifer Errick Former Associate Director of Digital Storytelling

Jennifer Errick Former Associate Director of Digital StorytellingJennifer co-produced NPCA's podcast, The Secret Lives of Parks, and wrote and edited a wide variety of online content. She has won multiple awards for her audio storytelling.

-

General

-

- NPCA Region:

- Mid-Atlantic

-

Issues