Spring 2014

Pipe Dreams

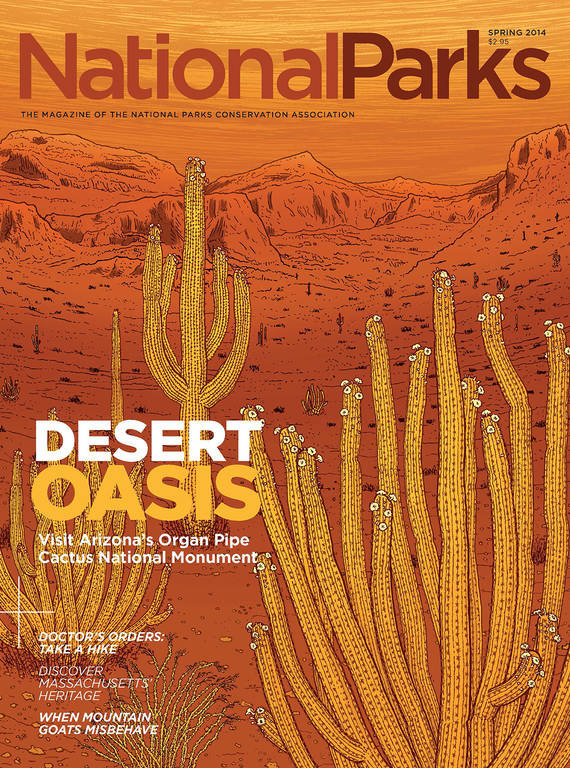

Head to Southern Arizona to Discover Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument.

I had to explain myself a lot in the days surrounding this trip.

“No, Organ, not Oregon. Organ Pipe. It’s a cactus. Not like your internal organs, like the musical instrument.”

In time, I learned to lead with “Sonoran Desert” and quickly explain that there’s a national park unit in southern Arizona called Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument.

“Near Mexico. No, not New Mexico….” And so on.

I could understand everyone’s bewilderment. The desert has never really been my area of expertise, least of all this region in the shadow of more famous park cousins like Joshua Tree and Death Valley. I expected a colorless landscape that was harsh and unknowable to an outsider with only a few days to spend there, but the desert immediately welcomed me, gently squashed my assumptions, and made me its champion.

Three hours west of Tucson, the land held enough scientific interest that in 1937 President Franklin D. Roosevelt set aside 330,690 acres for preservation as Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Despite Roosevelt’s intentions, ranchers won permits to continue grazing their cattle, even adding to their herds. Efforts to prevent mining were abandoned with the onset of World War II and the increased demand for copper and silver ore. In 1976, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization recognized the significance of the monument’s ecosystem and declared it an international biosphere reserve, and Congress designated it a wilderness area, effectively ending mining and ranching and finally realizing Roosevelt’s proclamation.

These days, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument attracts visitors from all over the world who seek the quintessential American desert experience. The arid landscape extends in every direction, with mountains always at the farthest edge, framing the picture. The monument boasts 640 native plant species, including its namesake, and is home to the only large concentration of wild organ pipe cacti in the United States. Pipe organs usually conjure images of European cathedrals and opera phantoms, but the way the plants’ enormous limbs stretched skyward prompted early botanists to name the species after the ornate musical instrument, in spite of the thematic incongruity. Older organ pipe cacti produce funnel-shaped, white flowers that open only at night and a red-fleshed fruit that can make watermelon seem, well… watered down.

TRAVEL ESSENTIALS

The park is 34 miles from anything more than a gas station and far removed from the sights and sounds of cities. That seclusion might overwhelm the first-time visitor, but probably only for a little while. The saguaro, that universal emblem of the Southwest, proves to be good company. Since these cacti are charmingly anthropomorphic, it doesn’t take long to settle into a feeling of being at a social gathering with just the right number of guests. Scattered and plentiful and posed in an infinite number of gestures, they appear to direct, supplicate, vogue, and even duel, providing ready entertainment without demanding undue attention.

I arrived at the monument in late September, traveling from northern California by way of San Diego, so I had the meteorological version of culture shock. I’m used to foothills blanketed with trees, so I was skeptical about finding beauty in a landscape so otherworldly it feels like a science-fiction movie set. September is not a busy month at the monument: Families are busy with a new school year, retirees up north aren’t cold enough to warrant the winter trek yet, and curious international travelers usually wait for the cacti to bloom in May and June. My travel companion and I were on our own—pitching our tent in an empty campground and seeing just two other people out on the miles of trails. Without distracting crowds, we were free to absorb the monument at our own pace, to hear everything it had to tell us. Nothing was blooming, yet it all felt distinctly alive; the balance lent a deeper sense of peace to a place already offering quiet and solitude.

If natural wonders were members of the Beatles, the desert would be George Harrison—contributing range and eloquence to the national parks but too often left out of conversations that focus on more famous subjects. The desert is patient, willing to parcel out awe in steady increments, allowing people to come to terms with its unique beauty at their own pace. Though it’s rarely regarded as approachable, it’s actually quite easy to get to know: Just walk right in. No great physical skill or specialized equipment is necessary to summit or spelunk it, and it offers a warm welcome year-round.

Scenic hikes are the primary activity at Organ Pipe. You can choose from the monument’s nine trails, ranging from easy to strenuous. Those confident in their compass and navigation skills can venture off trail and out into the canyons, though the trails are open only during daylight hours, at the request of the U.S. Border Patrol. Photographers, stargazers, and sunset aficionados also will find plenty to do at the monument, and history buffs can enjoy annual celebrations dedicated to its original inhabitants, the Pima, Tohono O’odham, and Hia C-ed people, who once had farmed and grazed on the land. Bikes are allowed on all roads open to vehicles, and strategic timing will reward wildflower enthusiasts.

EAT WELL IN AJO

If you’re not sure where to begin once you arrive, try one of the self-guided scenic drives. The Ajo Mountain Drive is a 21-mile, graded, one-way dirt-road loop designed to help visitors better understand the Sonoran Desert. It takes approximately two hours round trip and includes 18 points of interest, some with shaded picnic areas, some at trailheads, and one with restrooms. We wanted to see the big picture, so we chose to start our monument experience with this tour, despite having driven for several hours the day before. The scenic, meandering road offers an up-close look at the vibrant landscape. Visitors can stop at any time to explore the plants described in the free guide, which provides ample facts and historical context without reading like a textbook. About halfway through, we stopped asking things such as, “Now what’s that crazy plant?” because we soon discovered that the explanation was waiting for us on the very next page.

The monument was greener than I’d expected, and I soon understood why one legend has it that a Saudi prince once visited the Sonoran Desert and declared that it was a garden, not a desert. In addition to the saguaro and organ pipe cacti, jojoba, mesquite trees, palo verde, prickly pear, and the downright alien-looking ocotillo fill the landscape. My eyes kept stopping on the various cholla cacti, which look as Dr. Seussian as any plant can. Their tangled clusters of short arms are covered in white spines that, even from a few yards away, look like an enticingly soft fur coat. Chain fruit chollas have knotty braids of barbed fruit that hang off the ends of the arms, waiting for passersby to get close enough for the fruit to jump off and hitch a ride somewhere for a fresh start. Teddy bear chollas look impossibly fuzzy with their blend of brown and cream; I was far from home in a strange new place and surrounded by spikes, so their invitation to cuddle was a little cruel.

At stop ten, we set out to hike the Arch Canyon Trail and immerse ourselves in the environment. The moderate, two-mile trail affords views of the two arches formed in the rocks of Ajo Mountain and offers new perspectives on the surrounding canyons, which are much more substantial than they appear from the road. Finally out of a vehicle and walking through the desert, we felt less like tourists and more like guests at a housewarming party. We did a lot of stopping and simply gazing—the trail winds up Ajo Mountain, so the views change often. We made an accord with the wilderness while walking among the native plants: We promised to tread lightly, and we hoped they would keep their many, many needles to themselves.

Mount Ajo tops out at 4,808 feet and is largely formed of rhyolite left over from southern Arizona’s most recent spate of volcanic activity around 25 million years ago. Much later, ranching, mining, and Native American trade routes made use of the land, and some of their structures, including ranch houses, can be seen in Alamo Canyon and at the Victoria Mine. Organ Pipe ranger programs, such as guided hikes and talks, mostly take place in the busier months of January through March, but staff members are always happy to answer questions and provide context. My own stubborn independence waned in the face of overwhelming curiosity, and the volunteers at the visitor center graciously shared their expertise and their sincere affection for the park.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›If clouds move in toward the end of your day at the monument, get excited—it means you’re about to experience one masterpiece of a sunset. Settle in at your campsite with a glass of wine and wait for the show to begin. You can take as many photographs as you like. Just know that when you get home and show people your pictures, you’ll likely hear yourself saying, “This really doesn’t do it justice.” After the sunset come the stars, and the dropping temperature means a wholly different desert is stirring in the dusk; creatures that hid under, around, and inside cacti through the long hot day surface to prowl and partner, thriving unseen.

As my friend and I packed up the next morning, two ravens loitered unabashedly. We were the only ones there to people watch, after all. Perhaps they knew we had missed most of the blooming season and hadn’t glimpsed any of the monument’s adorable pygmy owls or beautiful Sonoran pronghorn, so it was only hospitable of them to offer themselves up as a farewell party. They hopped about genially, croaking occasionally, two seasoned and earnest diplomats for Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. I promised them I’d do what I could to send more guests their way, even if takes a lot of explaining.