Spring 2015

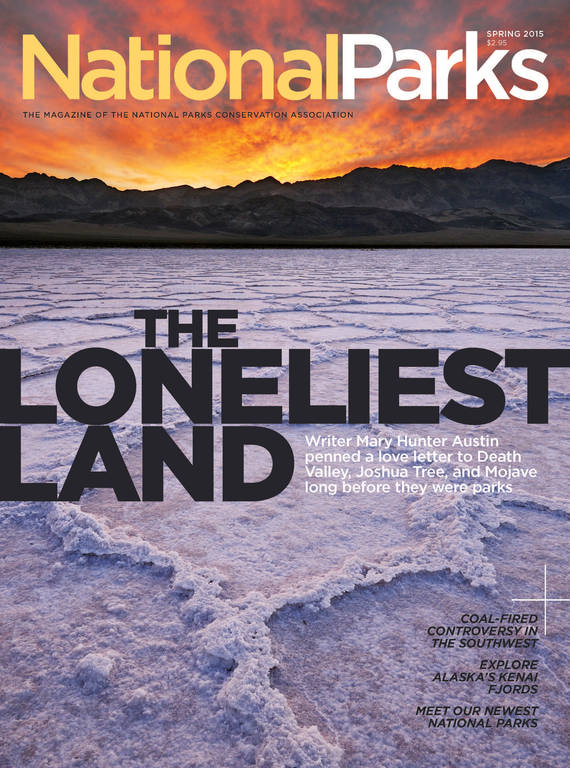

The Loneliest Land

In 1888, writer Mary Hunter Austin began exploring the desert. Her love of the blunt, burned land of little rain led to a book, a career, and an environmental legacy.

More than 100 years before Cheryl Strayed chronicled her solo adventures on the Pacific Crest Trail in her best-selling memoir, Wild, another young woman ventured into the arid lands of California alone. She had come with her family across the Tehachapi Mountains and into the San Joaquin Valley, north of Bakersfield, in 1888. As she explored, she was mesmerized by the landscape’s unsung beauty, its inhospitableness, and its people, who managed to prosper there. “There are hills, rounded, blunt, burned, squeezed up out of chaos, chrome and vermilion painted, aspiring to the snowline,” she later wrote. “Between the hills lie high level-looking plains full of intolerable sun glare, or narrow valleys drowned in a blue haze.”

For more than a decade, Mary Hunter Austin wandered the desert territory that she referred to as “land of little rain,” its Native American name. She made careful studies of the area’s flora and fauna and its people, both the native population and those, like her, who had come to live on the frontier.

Then, in 1903, she published a love letter to the lands that today include Death Valley National Park and the Mojave National Preserve. It took her 12 years to research, she said, but only a month to craft. Part travelogue, part memoir, part ethnography, the book, too, was called Land of Little Rain. Though the bulk of Austin’s writing has never entered the public consciousness like the work of conservationists John Muir and Aldo Leopold, Land of Little Rain is considered a seminal work of environmental writing, influencing authors from Terry Tempest Williams to Gary Snyder. While she became a prolific author, none of her subsequent books was so beloved and widely reprinted.

The book also made a deep impression on William Randolph Hearst III, grandson of the newspaper tycoon. “Within two or three sentences you’re transported to that world,” he says. “Long before Charlie Bowden and Edward Abbey became the men of letters of the desert Southwest, she created a kind of literary and poetic understanding of that country.”

Hearst was sufficiently enthralled that he decided to reissue the book with Counterpoint Press this fall. He wanted to include images that evoked the tone and lyricism of Austin’s text, so he engaged photographer Walter Feller, who had also been riveted by Austin’s book. What Hearst and Feller learned in researching the book was that Austin wasn’t just a pioneer in terms of where she ventured and how she wrote; she was a pioneer in how she lived her life.

Austin was born Mary Hunter in 1868 in Carlinville, Illinois, the fourth of six children. She was the daughter of a book-loving former Union Army captain in the Civil War and a mother of Scotch-Irish descent, fiercely concerned with temperance, religion, and book learning. Her father died when she was nine or ten years old. Later, Austin and her mother, with whom she had a tumultuous relationship, followed her brother out West, joining settlers taking advantage of the 1862 Homestead Act. The law encouraged western migration by way of cheap and easily attainable land. The family settled in the San Joaquin Valley in Central California. Austin was 20 and already defining herself as a writer.

PROTECTING THE DESERT

She took long walks in the desert, which was both “the loneliest land that ever came out of God’s hands” and one that “lays such a hold on the affections.” There she encountered and befriended all sorts of characters her mother would have considered distasteful: stagecoach drivers and miners and Paiute and Shoshone Indians. She noted the “unhappy growth of the tree yuccas” and the “bayonet-pointed leaves, dull green, growing shaggy with age, tipped with panicles of fetid, greenish bloom” of the Joshua tree. She wrote of the “hot sink of Death Valley” and “the long heavy winds and breathless calms on the tilted mesas where dust devils dance.” She was literate in reading the landscape, says Melody Graulich, a professor of English at Utah State University and an expert on Austin’s life and work.

The unusual path that Austin eventually followed—teacher, itinerant writer, single mother, divorcée—was greatly influenced by the landscape to which she was transplanted. “She wrote that in the desert each plant has its own face and its own social relationship to the plants around it,” says Graulich. “I see that as metaphoric space that the West gave for growth.” Austin had left behind the pretensions of the tamed landscape “and moved west where society was much more fluid. There was much more room for unconventionality.”

But Austin’s mother, ever concerned with respectability, was keen for her to marry. With the slim pickings in the frontier, Mary Hunter reluctantly wed Stafford Wallace Austin in 1891. Stafford, a Stanford-educated engineer, was not much of a provider and even less of a companion. Their daughter Ruth, born in 1892, was severely mentally challenged; for the most part, Austin cared for her on her own. She left her husband several times; they finally divorced in 1914. Unlike most women of her time, says Graulich, “Austin was not defined by marriage but by the natural world that gave these spiritual powers and independence.”

Throughout the hardship and turmoil, Austin was writing, not just to express herself and give voice to the causes so dear to her heart but to earn a living and pay for her daughter’s care. Although some would condemn her choice, Austin eventually put her daughter in an institution, a financial cost she would shoulder alone.

Land of Little Rain began as a series of sketches—it includes 17 vignettes in all—published serially in The Atlantic, the most important literary magazine of the day. Much of her territory is in the Owens Valley, where she made her home, between the Inyo National Forest and Death Valley. The chapter “Jimville” describes a town of “300 people and four bars,” and “The Basket Maker” focuses on a Native American woman who “sits by the unlit hearths of her tribe and digests her life, nourishing her spirit against the time of the spirit’s need.” The book, says Graulich, is “the beginning of gaining her footing, both in the physical landscape and the literary landscape.”

Eventually Austin left the Owens Valley and headed to an artists’ colony in Carmel, where she befriended writers like Jack London and Ambrose Bierce. She went on to become a fierce political voice on water issues, Native American rights, and other causes related to national parkland, and an important figure in the dawn of the Southwestern arts scene. “She had no qualms about putting herself out there,” says Graulich. “She had her finger in every pot.”

Austin was particularly passionate about women’s rights and birth control. Many of her later works recount the struggles of independent-minded women in a repressive society. As Austin wrote in a fictional piece called The Walking Woman: “She had walked off all sense of society.”

“Her books are about the women she encountered in her wanderings—mystical, independent, farseeing women who had a deep, abiding connection to the natural world,” says Graulich.

Later, in New Mexico, Austin collaborated on a project with Ansel Adams, who said of her, “Seldom have I met and known anyone of such intellectual and spiritual power and discipline. She is a ‘future’ person—one who will a century from now appear as a writer of major stature in the complex matrix of American culture.”

Although Adams’ prediction never materialized, Austin’s best-known book continues to influence writers and artists today.

“It was this great description of the unique landscape of the Owens Valley, but also a larger land of the desert and the people who might be drawn there,” says Dayton Duncan, a writer and filmmaker who co-produced the PBS series, The National Parks: America’s Best Idea. Duncan discovered the text while researching his book about modern frontier towns, Miles from Nowhere. “It’s as evocative a benchmark as reading Lewis and Clark’s journals.”

To some of her fans, this book’s popularity is something of an irony, or a sad commentary on the publishing industry. Land of Little Rain, her least controversial and confrontational work, has quietly lived on while many of her more overtly feminist and political works fell out of print. Some believe that its political neutrality is part of what has kept Land of Little Rain from fading away.

Austin went on to write 33 other books. She moved to New York in the early 1910s to champion women’s causes, and there she wrote the autobiographical novel,* A Woman of Genius*, about an actress whose artistic aspirations conflict with the expectations of society. In 1918, she began visiting Santa Fe, where she studied the poetry of Native Americans and engaged in reform on their behalf. She collaborated with Ansel Adams on Taos Pueblo, about an intact Native American village, in 1930.

Just after the release of her book, Experiences Facing Death, a meditation on spiritualism, philosophy and war, she began to suffer from a recurrence of serious health problems. In 1932, she was diagnosed with coronary disease and had a heart attack the following year. She died in Santa Fe in 1934. Many of her books died with her.

Land of Little Rain, of course, endured. It has been reissued many times, but Hearst contends that his iteration does something the others do not: It paints a more complete picture of Austin and her work, thanks in part to a comprehensive afterword by Graulich that notes the breadth of Austin’s passion and causes, her complexity of character. “The book we’ve produced is a very modern interpretation of Mary Austin’s work and life,” he says.

It’s also one of the first to acknowledge the often overlooked truth of Land of Little Rain: It’s not really a work of nonfiction.

Hearst found this out the hard way. For years, he had been interested in finding the places Austin mentioned in her book. “If you like Mary Austin,” he says, “you want to make a map between the chapters of her work and the physical geography.”

Somehow, in his fervent research of Mary Austin’s haunts, Hearst came across Walter Feller, a former water-district engineering technician who moved to Hesperia, California, just north of the San Bernardino National Forest in 1986. When Feller found Austin’s book in a welcome center, he was hooked. “She wrote with such loving familiarity of her area,” he says. “Her book has been a major part of my life.”

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›The two of them set out on what Hearst called a “voyage of discovery” but quickly found that many of her locations could not be pinpointed. “There were places that just didn’t exist,” Hearst says. “They were just not on the map.” Her whole chapter on Jimville, for instance, wasn’t about one real place but perhaps was a composite, a painting in words of her collective experience in desert towns. In the end, says Hearst, they came to the inevitable conclusion that large portions of her work relied on imagination.

This didn’t bother Hearst. He’d come to Austin as a fan of Western literature, which included fiction. “I don’t think it subtracts anything that it was fiction,” he says. “In fact, it separates the inspiration part of the landscape from the Google Earth part of the land.” Many scholars of her work, including Graulich, had long known that parts of the book were fictional—the writer Bob Hass called Austin a “mythographer”—but most of the general public did not.

Hearst found a professional cartographer to make maps of the places they actually could identify, spots like Little Antelope and Butter Lake, and Feller picked the photographs that he felt most matched her words, even if the images weren’t of the specific lands in her book.

Hearst hopes that the fictional places in the book won’t deter a new generation of fans of Austin and the land she loved but will inspire them. His wish, he says, is that readers will “put a sleeping bag in the back of their cars and drive out there to see the country.”