Fall 2014

Red Rocks

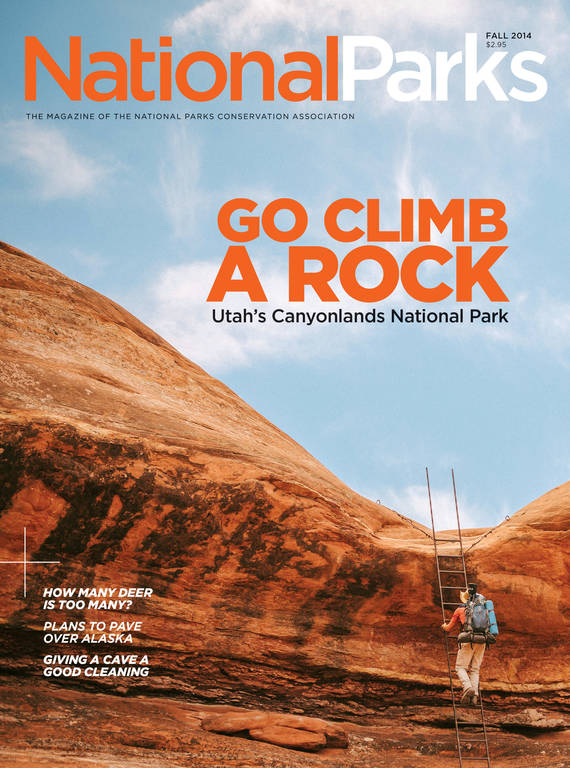

Wander through the Maze, the Needles, and the Islands in the Sky at Canyonlands National Park.

After following a trickling desert canyon stream surrounded by rocks that resemble 20-foot mushrooms, I need to start scrambling when the trail turns to slickrock. It’s not hard. Cairns—small rock piles—mark the way, and the wind is company enough. Then I reach a sign that points to what looks like an impossible pass over a red rock wall to the next canyon. “No way,” I mutter to no one.

Suddenly, clambering around by myself in Canyonlands National Park, one of the most remote and rugged parks in the system, doesn’t feel like such a good idea.

Part of the grand Colorado Plateau and the largest of the five national parks in Utah, Canyonlands is a land beyond hyperbole, a place where “Wow!” doesn’t come close to summing up the scenery. Think: supreme, vast, massive, lofty, sublime, pristine, extreme, phenomenal, mystical, and stunning. Here, the Green River meets the legendary Colorado, where they combine to form Class V rapids, the best—or some would say worst—world-class whitewater around, in the tumultuous Cataract Canyon. In the park’s 527 square miles, the adrenaline junkie meets the untrammeled wilderness lover.

TRAVEL ESSENTIALS

Canyonlands—a place where only American Indians, cowboys, river explorers, and uranium prospectors dared to tread before Congress declared it a park in 1964—is divided into three sections. To reach all three distinct land parcels, visitors must exit the park and travel a couple of hours. The Island in the Sky is a high-altitude desert mesa wedged between the two rivers with 100-mile panoramic views that rival those of any other place on the planet. The Maze, a labyrinth of sandstone, makes even the most experienced backcountry hiker wary. It’s one of the nation’s most remote areas. Lastly, the Needles, named for its distinctive sandstone spires, is truly a hiker’s paradise, with more than 60 miles of interconnecting trails, few paved roads, and whimsical, otherworldly monoliths in almost every direction. After three days in this section alone, I left wishing I had more time.

On my first day in the park, Island in the Sky’s massive 6,000-foot-high cliffs made me feel insignificant as I stood on the edge overlooking an ancient coastline. This showcase of geology began about 300 million years ago, with sediment deposited from the ancestral Rockies and even the Appalachians. Today’s desert expanses were once shallow seas that advanced and retreated, leaving behind sand, salt, and marine limestone that eroded into needles, fins, and arches that make the scenery on any hike worth a few blisters.

I headed to Murphy Point just as the sun’s rays began illuminating the park’s exotic silhouettes. The two-hour route overlooked the vast basins below the mesa top. Without spotting a soul, I felt like the last person on Earth. But that solitude set me up for a little disappointment when I ran into a couple on the White Rim Overlook lingering in “my” perfect picnic spot. Still, there was plenty of space to ferret out another site with a view nearly as perfect.

I closed the day on the Grand View Trail, which looks out over much of the park, including the river canyons, the pinnacles, and the distant La Sal and Henry Mountains. The easy, 1.5-mile level trail was the most crowded in the park, but I timed it so I finished at sunset and had the whole place to myself. The windless night made the silence so powerful I could almost hear it.

Peering down into the canyon all day from afar made me feel like I was floating over the landscape, and I craved a trip into the canyon. So the next day, I jumped in a four-wheel-drive truck with Matt Bigler, a guide with NAVTEC Expeditions based in Moab, to travel down unpaved switchbacks with sheer drop-offs on the Shafer Trail Road. After a 1,200-foot vertical descent, we connected with the White Rim Road, once used by miners. It winds down to Musselman Arch, a walkable natural stone bridge, and Thelma and Louise Point, the scene of the 1991 movie’s car-plunge finale. Before that, Bigler told me, it was called Fossil Point.

The highlight for me, however, was the five bighorn sheep we spotted from above. Only about 4 percent of the bighorns’ historical population remains—with a few hundred staking claim to these rocky ledges. This makes the park crucial to the species’ future. Other inhabitants that mostly go unseen in corners rarely touched by humans are black bears, bobcats, and mountain lions. I kept my eyes peeled, but never did see any prints in the sand.

The next day, in Horseshoe Canyon, the seven-mile round-trip hike took me to some of North America’s most significant Indian rock art. Part of the Maze, Horseshoe Canyon sits disconnected to the northwest, and it’s about a two-and-a-half hour drive from Moab. (Primitive camping is allowed on Bureau of Land Management sites near the trailhead, but if you don’t camp, allow for an entire day.)

SIDE TRIP: NEWSPAPER ROCK

The 750-foot descent on slickrock to the secluded canyon bottom felt easy, although I knew I’d be huffing and puffing in the blazing sun on the climb back up. I didn’t think too much about it, though, because I was immediately captivated by the foot-long, three-toed dinosaur track about a half-mile in.

The loose sand at the bottom makes hiking a little difficult, but reasons to rest abound: oases of mature cottonwood, an intermittent stream brimming with tadpoles, and pockets of quicksand to muck around in. For most of the 7.5-mile roundtrip, though, I gawked at the vivid red, sheer sandstone erupting into the cerulean blue sky.

Of the four major rock-art sites in the canyon, the Great Gallery is often labeled the world’s best; it includes pictographs and petroglyphs of life-size, mummy-like figures that lack arms and legs, painted and etched 2,000 to 8,000 years ago by prehistoric peoples. Before heading back, I contemplated the artwork for at least an hour with the help of a well-versed volunteer who pointed out details I would have missed.

After Horseshoe Canyon, I decided to spend the next day on some shorter hikes in the Needles. Even though it’s known for its longer treks, the Needles District has a few excellent hikes off the short six-mile paved road. Pothole Point is a fascinating mesa of depressions that collect rainwater and trap windblown sand grains and pebbles. Unfortunately, I visited a little too early in the season so I missed seeing the tiny creatures—fairy shrimp, beetle larvae, and snails—that spend their entire lives in the murky puddles. (Don’t touch, though! Oils, lotions, and sunscreen pollute the waters and harm the inhabitants.)

From there I headed to nearby Slickrock Trail, which leads to a series of four overlooks and includes a panoramic view of much of southeastern Utah and an overlook of Big Spring Canyon. This is the canyon that befuddles me on my fifth and final day when I lack the confidence to cross the canyon wall in front of me.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Even though the Park Service has carved notches in the rock to help hikers with their footing, at 5’1”, I’m too short to reach them easily. Disheartened, I turn back. But then I tell my quivering legs that it really doesn’t look that bad. Walking back on a slickrock slant to the crossing, I stretch my hand to one of the shallow holes, positioning myself so one foot might follow. But again I talk myself out of it and sit down, totally bummed.

That’s when I hear voices and soon see two specks rounding a giant rock toadstool on the path I came up on. I gesture toward the canyon wall and call down: “I chickened out, but now that you can hear me if I scream, I’m giving it shot.”

As quickly as I can—to avoid thinking—I pull myself up on the rock, stick a knee in a notch, flatten my body, and reach out my arms like a tree frog suctioned to the side of an aquarium. When I make it over I stand slackjawed—the scene is even more spectacular on the other side. It makes me almost forget to call out a thank you. The “You’re welcome!” rings out loud and clear.

About the author

-

Heidi Ridgley Contributor

Heidi Ridgley ContributorHEIDI RIDGLEY writes about history, travel, and wildlife conservation from Washington, D.C.