Summer 2023

‘A Very, Very Long and Vast Rabbit Hole’

Fifty years ago, someone stole an antique pistol from the Springfield Armory Museum. This spring, the case finally came full circle.

On a summer day in 1971, a staff member at the Springfield Armory Museum in Western Massachusetts passed a display case and did a double take. The glass container had been jimmied open, and its contents — a rare brass, iron and wood single-shot pistol dating from the mid-19th century — had disappeared.

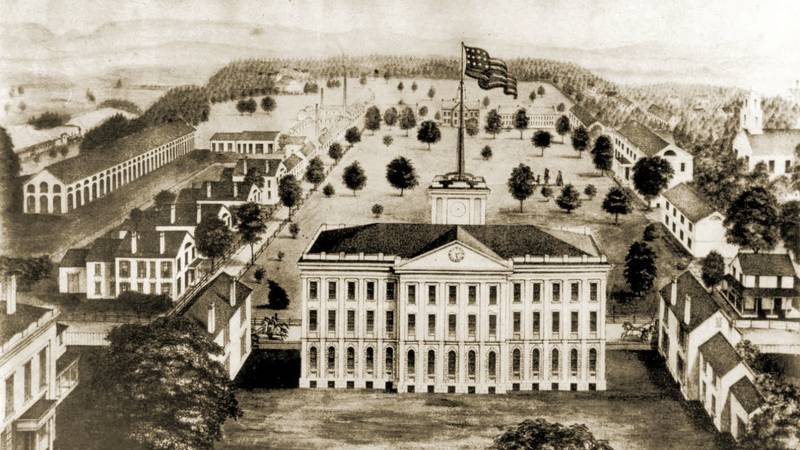

The armory, first established as a federal arsenal in 1777, stores some 7,000 weapons within its red brick walls, but this wasn’t just any old gun, according to Alex MacKenzie, curator for the Springfield Armory National Historic Site, which has managed the museum’s collection since 1978. For starters, it was never intended to be fired. The armory created just 12 of these pattern pistols in 1842 to serve as physical blueprints that the U.S. government supplied to manufacturers to reproduce. On top of that, the pistol’s design, namely the novel use of interchangeable parts, represents a turning point in history. “It’s kind of the birth of the industrial revolution in a way,” MacKenzie said.

MacKenzie called the pistol’s 1971 theft “brazen” before explaining that on the same June day, 30 miles down the road, a Colt Whitneyville Walker revolver was snatched from the Connecticut State Library. “This wasn’t a random thing,” he said. “It was the same person.”

Unfortunately, there was no security footage to review. No fingerprints to be had. The event appears to have barely made the news at the time, receiving just a single sentence in the Springfield Union crime report. Museum staff documented the theft as best they could, and then resumed normal business. The case went cold.

Nearly four decades later, when the story seemed destined to remain a historical footnote, a gentleman walked into the Upper Merion Township Police Department in Pennsylvania, some 250 miles away, with a seemingly unrelated tip. That lead sparked a yearslong investigation into an art theft puzzle spanning several states and agencies and far more artifacts than just the Springfield pattern pistol and the Connecticut library revolver.

But enough foreshadowing. Let’s return to 2009 when police officers Andrew Rathfon and Brendan Dougherty took a concerned citizen’s statement. The man reported that he’d been to an antique gun show in a nearby town and believed one of the weapons he’d seen there had been stolen from the Valley Forge Historical Society in the 1970s. (The society’s collection has since been absorbed by the Museum of the American Revolution.) “Obviously, the two of us weren’t working in the ’70s. We weren’t born,” said Rathfon. “We didn’t know what the old guy was talking about, but we thanked him, and we started looking into it.”

This is the only case I’ve ever brought home.

The clue wound up being a dead end; the gun in question hadn’t been stolen. By that point, however, the detectives’ curiosity was piqued, and they began thinking about the 75 or so weapons that had gone missing from the local historical society in the lead-up to America’s bicentennial. “Wouldn’t it be cool,” Rathfon remembered asking, “if we could just get one of these back and bring it back to Valley Forge?” And so, in their free time at work, the two self-professed history lovers began to poke around.

“We probably spun our wheels for years trying to figure out what we were even looking for,” Dougherty said. After all, high-value art crime was not their typical beat. But the officers persevered, compiling a directory of museum thefts involving stolen weapons, including the Springfield pistol. Some five years after that initial tip came in, they had a breakthrough. They realized that rather than looking for missing objects, they needed to be looking for the people capable of committing such a crime. That change in strategy, Dougherty said, “led us down a very, very long and vast rabbit hole.” (To underscore his point, Dougherty nodded toward Rathfon’s bald pate and said, “Andy had hair when we began this case.”)

Springfield Armory National Historic Site

At Springfield Armory National Historic Site, you can tour the largest collection of shoulder arms outside Britain, and see how these weapons were made at the armory that supplied the…

See more ›With their supervisors’ approval, they embarked on long road trips, crossed state lines, ferreted out details from anonymous calls and letters, conducted countless interviews and eventually landed on a suspect, someone their contacts made them believe could be in possession of the weapons. (If the details here seem murky, that’s intentional. The detectives are serious about protecting their sources.) The man in question, an antiques collector by the name of Michael Corbett, lived in Newark, Delaware, well outside their jurisdiction. So, Dougherty and Rathfon looped in the FBI Art Crime Team and the U.S. Attorney’s Office, who helped secure a search warrant. In 2017, all parties descended on Corbett’s house.

“We found a lot more than we were bargaining for,” Rathfon said. All told, law enforcement personnel removed more than 100 objects — predominantly historic weapons but also pewter plates, lamps and even a powder horn dating from the French and Indian War — from Corbett’s attic and a basement safe. Each item’s provenance took time to determine. The FBI returned the artifacts Corbett legitimately owned; the rest they retained as evidence.

Last August, Corbett pled guilty to the possession of stolen goods that had been transported across state lines. In exchange for handing over an additional stash of treasures, Corbett was sentenced to one day in federal prison, a $65,000 fine and a stint of house arrest. (The statute of limitations prevented prosecutors from bringing charges related to the original thefts.) The firearms that launched the detectives’ initial quest were not among the items confiscated, but the second haul — produced by Corbett the day after Labor Day — included a dozen guns stolen from the Valley Forge Historical Society, the Connecticut State Library’s Colt Whitneyville Walker revolver (likely worth over $1 million), and Springfield Armory’s pattern pistol. (Corbett could not be reached for comment, but his lawyer described him as “a self-taught expert” with an “eye” for the rare and valuable.)

This March, with the case’s conclusion, a repatriation ceremony was held at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia, and 50 pilfered historic objects, including the armory’s pistol, were returned to elated staff at 17 institutions from Mississippi to Massachusetts. Museum curators shared stories about their artifacts before each of the items was packaged up and taken back to its rightful home.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›The tales of objects lost and found moved Dougherty and Rathfon, both of whom attended the celebratory affair. “We were shocked how meaningful some of these items were to the history of these places,” Dougherty said. A cop for more than 20 years, he prides himself on maintaining a firewall between his work and private life but admitted that he couldn’t shake this case. “This is the only case I’ve ever brought home,” he said, adding that it was “an absolute privilege to work on.”

Back at Springfield Armory, MacKenzie is in the process of preparing the recovered pistol for public viewing. This involves meticulously stripping away the corrosion that accumulated during its long spell in less-than-pristine holdings. But aside from the oxidation, “it’s pretty much exactly as it appeared when it was first made in 1842,” he said, marveling at what he called the “mint” condition of its internal workings.

Rathfon and Dougherty relish the idea of visiting Springfield Armory with their children once the pistol is back on display. They’ll point to the antique, Rathfon said, and tell them, “’Your dad and his partner, we got that piece back so that everybody else can see it.’”

About the author

-

Katherine DeGroff Associate and Online Editor

Katherine DeGroff Associate and Online EditorKatherine is the associate editor of National Parks magazine. Before joining NPCA, Katherine monitored easements at land trusts in Virginia and New Mexico, encouraged bear-aware behavior at Grand Teton National Park, and served as a naturalist for a small environmental education organization in the heart of the Colorado Rockies.