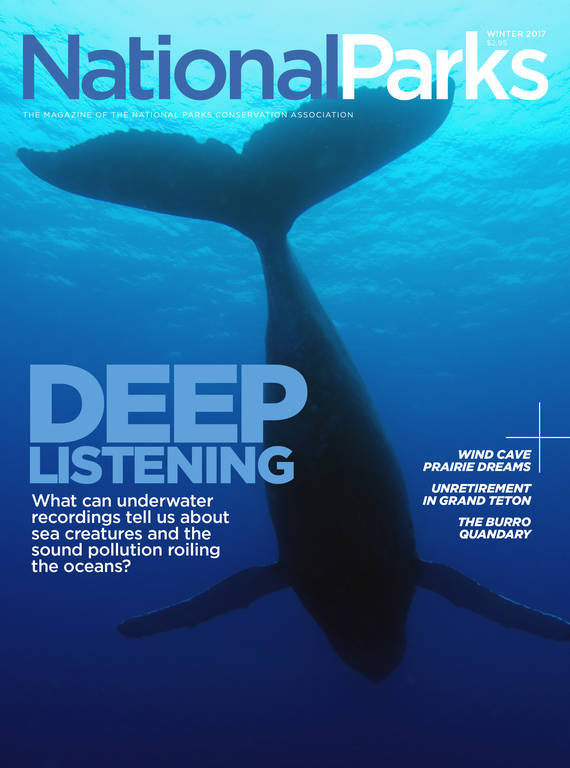

Winter 2017

Deep Listening

How can the world’s largest collection of underwater sound recordings help scientists understand sea creatures and the noise pollution that may be killing them?

The familiar moans of humpback whales are just the beginning. Scrolling through the online database, you hear squeaky calls of belugas, whistling dolphins and sperm whales unleashing rapid clicks to locate squid. Walruses, weirdly, sound like drum machines. And maybe most surprising is the vocalization of the bearded seal: It’s an eerie, wavering pulse, like a special effect in a 1950s sci-fi flick. If it feels like you’re eavesdropping on an alien world, no wonder — that’s exactly what you’re doing.

Thousands of hours of these sounds are contained in the William A. Watkins Collection of Marine Mammal Sound Recordings and Data, the largest store of underwater audio recordings ever compiled. Collected over seven decades, the archive was acquired in 2015 by the New Bedford Whaling Museum, which is located within the New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park in Massachusetts. Though transfer of the materials to the museum isn’t yet complete, much of the content is now freely available through a website developed by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Launched over the summer, the interface allows scientists and casual listeners to sample around 16,000 clips (including dozens of “best of” cuts) and 1,800 complete master tapes. This data is a boon for researchers studying marine mammals, but the archive could also provide clues about the state of the world’s oceans, which grow louder every year.

Watkins and his colleagues would chase aquatic sounds across the globe, from the waters of Alaska to Antarctica.

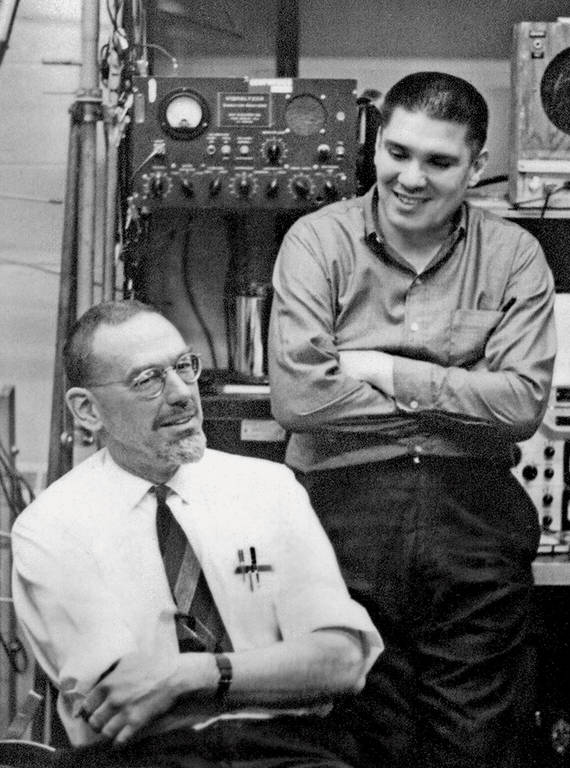

© COURTESY OF THE WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTIONA pioneer in the field of bioacoustics, Bill Watkins made many of the recordings with hydrophones — underwater microphones — he built himself. Over a 40-year career at WHOI, he and his mentor and research partner, biologist Bill Schevill, captured the first recordings (known as “vouchers” to scientists) of dozens of species. In short, they opened human ears to the oceans.

Raised by Christian missionary parents, Watkins grew up in Guinea, West Africa (called French Guinea at the time). After studying anthropology in the U.S., he set up a radio station in Liberia. By then, he could speak more than 30 African languages but had never used his ear for speech to interpret the otherworldly voices of whales, dolphins and seals. He came to marine mammal science indirectly when, in 1958, WHOI hired him to build tape recorders that could withstand conditions on boats.

Back then, underwater recording was a clunky business. The first recording of any marine mammal — a beluga whale, in 1949 — was made by Bill Schevill using a dictaphone, a cousin of Edison’s phonograph. Hydrophones and amplifiers were large and not designed for use at sea. With funding and input from the U.S. Navy, Watkins shrank and adapted these technologies. His “rowboat recorder” allowed researchers to approach and record marine life from small boats, which was much less disruptive to animals’ natural behaviors. Watkins and his colleagues would chase aquatic sounds across the globe, from the waters of Alaska to Antarctica. “In those days, almost every animal contact was brand-new exploration,” he said in a 2000 interview. “We were all flying blind.”

Watkins’ techniques laid the groundwork for the study of marine mammals in the wild. He was the first to use “arrays,” or arrangements of multiple hydrophones that help pinpoint sources of sound, to record animals. He also developed some of the first wildlife tags — precursors to high-tech marine mammal tags of today, which track sound and motion and are applied with suction cups. The data led to numerous discoveries, allowing him, for example, to attribute certain calls to species such as sperm whales and fin whales. Eventually Watkins would receive a doctorate in whale biology from the University of Tokyo, defending his thesis in Japanese.

Since the 1980s, Watkins had hoped to make his trove of sounds — which eventually included recordings donated by fellow researchers who wanted to contribute to the archive Watkins was amassing — available to the scientific community and the public. “The idea of the database and the digitization was really his baby,” said Michael Moore, director of the Marine Mammal Center at WHOI. But as WHOI researchers continued their painstaking work to digitize Watkins’ data after his death in 2004, they worried about properly preserving the boxes of reel-to-reel tapes, hand-built transistors and other artifacts he left behind. “Housing an acoustic collection was overwhelming,” Moore said. “We all felt the archive needed to be curated in a museum of quality.”

So one day, while on a research cruise, Moore contacted the New Bedford Whaling Museum, where he serves on the board, and offered up the collection. “He literally picked up his cell phone on the boat and called the director,” said Laela Sayigh, a biology specialist who worked with Watkins and was on the same research trip. When the director expressed interest, Moore and Sayigh arranged with the WHOI administration for all of Watkins’ recordings and papers, along with photos, videotapes and instruments that detect and measure sound, to be gifted to the museum. They insisted on one big stipulation: that no one would ever be charged to access the collection, according to Watkins’ wishes.

Though official handoff is scheduled for the end of the year, some of Watkins’ instruments are already displayed in an exhibit in the Jacobs Family Gallery, where four full whale skeletons — including a North Atlantic right whale mother and unborn calf, killed by a ship strike — float overhead, suspended by cables. The museum is building a temperature-controlled facility to conserve and house the materials.

At first glance, a museum focused on Yankee whaling may not seem like the obvious place for a collection of 20th-century recordings. An anchor of the 13-block national historic site, not far from the city’s active scalloping fleet, the museum — which is operated by the Old Dartmouth Historical Society — chronicles the history of the New England whale fishery. Inside, cases of harpoons and lances, a half-scale whaling vessel (at 89 feet long, the Lagoda is the world’s largest ship model), and an amazing assemblage of scrimshaw (whalebone carved into everything from chairs to pie-crimpers) evoke scenes from Herman Melville’s “Moby-Dick.” This era of bloody, ocean-wide hunting persisted until the U.S. essentially banned commercial whaling in 1972.

But the museum casts a wide curatorial net that extends beyond the region’s whaling past, which peaked in the mid-1800s before the advent of industrial whaling. “Part of the museum’s mission is to tell the history of man’s interactions with whales worldwide,” said Christina Connett, the curator of exhibitions and collections. “So we talk about the spiritual, the business of whaling, the conservation story, Melville’s story and the romance of the sea.” Connett pointed out that whalers, like biologists, were keen observers of whales, keeping meticulous logbooks and journals on their voyages (the museum has 2,700 in its library).

Much later, studies by Watkins, Schevill and others would reveal whales and dolphins to be highly intelligent creatures, capable of learning and complex communication. Cetaceans, we now know, use a wide range of sounds to identify each other, migrate, attract mates and find prey in pitch-black ocean depths through echolocation. Some calls, like the low-frequency rumbles of blue whales, can travel thousands of miles.

In light of the Watkins archive acquisition, the museum is aiming to incorporate more audio into exhibits. At a special kiosk, visitors can listen to clips of several species, as well as the screech of sonar, which is thought to disrupt navigation of toothed whales and has been linked to mass strandings. Meanwhile, museum staff will continue digitizing Watkins’ analog tapes. Some will have to be baked in ovens to repair degraded enamel before their information is carefully transferred to a digital format, Connett explained.

The field of bioacoustics has changed dramatically in the last half-century, and so have the sound profiles of the world’s oceans: They’ve gotten much, much louder. And humans are mostly to blame. According to studies by Scripps Whale Acoustic Lab, man-made (or anthropogenic) noise in oceans has doubled every decade for the last 50 years. The main culprit is trade shipping, though Navy sonar and seismic air guns that detect oil and gas deposits by blasting into the seafloor — with a force 100,000 times louder than a jet, every 10 seconds, often for days at a time — are also flooding acoustic habitats. “It’s very well-documented that ambient noise levels in oceans have increased steadily,” said Sayigh, who has studied dolphins in the din of Florida boat traffic for years. She said such disturbances could mask feeding calls of endangered right whales or separate mothers from their calves. “I do worry what it’s like for the animals. It’s hard for us to relate to since we’re not in that world.”

Research by conservation groups, university labs and government agencies like the Office of Naval Research suggests that intense noise can drive off marine mammals, shock them into silence or damage their hearing organs, sometimes causing death. Military sonar is believed to confuse deep-diving beaked whales, so that they beach themselves or surface too quickly and suffer a cetacean version of the bends. In 2015, in response to a lawsuit filed by environmental groups, the U.S. Navy agreed to limit sonar testing in vital ocean habitats near Southern California and Hawaii.

When the undersea cacophony is considered alongside other threats, such as ship collisions and fishing net entanglements, life for marine mammals can seem as inhospitable as in the old commercial whaling days. “We’re not killing whales with harpoons so much anymore,” said Moore, “but we’re routinely killing them with ships and fishing gear.”

This human degradation of oceans — and the call to conserve them — is a story that the New Bedford Whaling Museum staff feel a need to illuminate for visitors. “We have a responsibility to create awareness that these animals communicate via sound, and we’re making it harder for them to do that,” said Robert Rocha, the museum’s director of education and science. He offered a stark parallel: “Go stand next to a busy highway for the rest of your life and try to have conversations there.”

Fortunately, promising initial steps to quiet oceans are being taken. In June 2016, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration released a draft of an Ocean Noise Strategy Roadmap, the start of a 10-year plan to assess the human impact on underwater acoustic environments and take measures to reduce ocean noise. Some NOAA divisions are already using quieter research vessels, and in 2014, the International Maritime Organization adopted guidelines for cutting noise levels of commercial ships — installing noise-dampening propellers and insulating engines, for instance — though the modifications are still voluntary. If employed on a large scale, according to some experts, such technologies could muffle ship noise by up to 99 percent.

Kurt Fristrup, an acoustic expert with the National Park Service, understands both the threat posed by sound and the value of audio recordings. Years ago, before becoming chief scientist for the Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division, he worked alongside Bill Watkins as a research specialist at WHOI, developing methods of digitizing and searching acoustic data with computer algorithms. “When you make a recording, you capture this historic vignette of what conditions were like,” he said. “It allows us to look at deeper aspects of change over time.”

Fristrup considers Watkins a crucial early mentor. “The education I got with Bill empowered me to do the work I’m doing today with the Park Service,” he said. The Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division, based in Fort Collins, Colorado, studies soundscapes of public lands and waters, along with effects of light pollution, to better manage and protect those natural spaces. So far, Fristrup’s team has made recordings at over 600 locations in parks ranging from Zion to Denali. Extrapolating from those data — around a million hours, he said — they’ve created visual maps of sound levels across the entire U.S.

Although noise pollution in both air and sea is on the rise, Fristrup said that given the ephemeral qualities of sound, his outlook is never entirely grim. “The great thing about noise is that once you stop producing it, the environment instantly gets better. The potential for immediate improvement is there.”

For scientists trying to grasp the effects of changing noise levels in oceans, the Watkins archive has proved uniquely useful. In a study by Susan Parks, a professor of biology at Syracuse University, recordings of North Atlantic right whale calls from the 2000s were compared to Watkins and Schevill’s right whale cuts from the 1950s. At first, Parks thought the older recordings had been slowed down, until she realized the whales were calling in a different pitch.

“The whales had shifted the frequencies of their vocalizations over those decades,” said Sayigh, who is familiar with the research. Higher calls, she explained, can be heard more clearly amid droning ship traffic. “So that’s one really cool example of using these historical recordings to document changes that are likely noise-related,” she said. “There’s a lot of potential for similar types of studies.”

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›The archive also could help to identify animals whose calls have been captured by moored recorders around the world. “The database has some good recordings of lesser- studied species,” Sayigh said. “Especially for endangered animals, it adds to our understanding of their distribution patterns. I could certainly see it having conservation implications.” Since marine mammals spend much of their lives at great depths, listening is often the only way to find and track them, and to estimate how many are left.

But the Watkins archive also documents 70 years of human clamor in oceans. Beneath the calls of whales and seals, a parallel soundtrack of ship propellers and pinging sonar runs through the recordings. As we continue to reckon with a loud world, Fristrup said, the collection will be an important reference point for researchers who are monitoring efforts to quiet the seas.

“Going forward, people will pay much more attention to the background of those recordings than the foreground,” he said. “Watkins’ work speaks to the present.”

About the author

-

Dorian Fox

Dorian FoxDorian Fox is a writer and freelance editor whose essays and articles have appeared in various literary journals and other publications. He lives in Boston and teaches creative writing courses through GrubStreet and Pioneer Valley Writers' Workshop. Find more about his work at dorianfox.com.