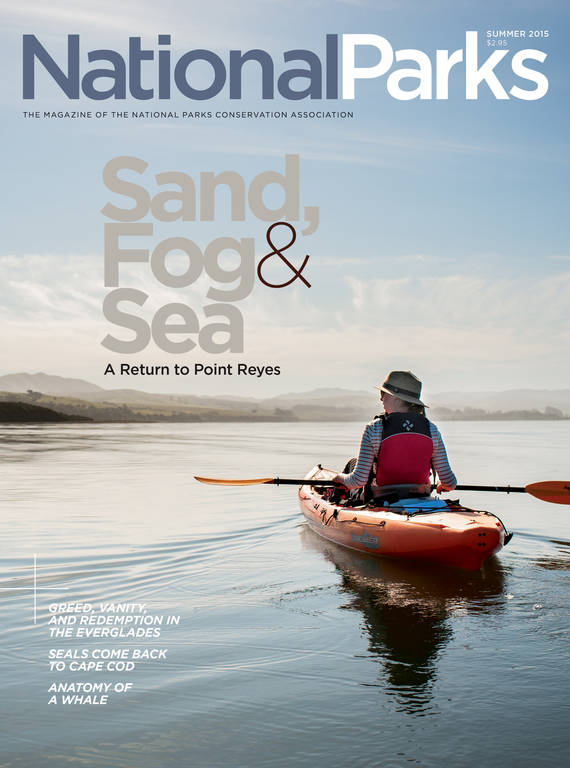

Summer 2015

John Brown’s Soul

John Brown hoped to end slavery when he raided a federal armory at Harpers Ferry in 1859. His plan failed, but he still changed the course of history.

“You can weigh John Brown’s body well enough, but how and in what balance weigh John Brown?” poet Stephen Vincent Benet wrote in 1928. These words, which greet visitors entering the John Brown Museum at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park in West Virginia, serve as a reminder of the complicated legacy of the man whose dedication to ending slavery led him to raid a federal armory here. The raid fanned the fire that split the nation, and more than 150 years later, Brown remains a compelling and divisive figure.

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park

As a vital early American town, Harpers Ferry has been the site of a number of historical events. It was a point of supply for Meriwether Lewis’s Corps of Discovery,…

See more ›“We cannot come to a common definition of the meaning of John Brown,” says Dennis Frye, the park’s chief historian. “His soul goes marching on inside every American.”

In 1859, Brown and his 18 followers—black and white—crossed the Potomac River from Maryland into Harpers Ferry, seized the night watchman at a railroad bridge, and quickly occupied the federal armory without a single shot. Brown’s plan was to wage economic warfare against the slaveholder oligarchy, using violence if necessary. With firearms from the armory, his guerrilla army would liberate slaves and then escort them through the Appalachian Mountains to the North. He planned to remove the South’s most valuable commodity plantation by plantation, bankrupting slaveholders overnight and rendering their business model untenable.

But the inaugural raid unraveled almost as rapidly as it began. The night watchman escaped and halted an arriving train, just short of the station. Brown’s men shot an inquisitive baggage porter, which awakened a town doctor, who arrived to investigate. Brown’s men allowed the doctor to examine the dying porter—a free black man, in a tragically ironic twist—then let him go. Instead of heading home, the man grabbed a horse, galloped to nearby Charles Town, and loudly announced that abolitionists had seized the town. Church and fire bells suddenly clanged into chorus. By noon, nearly 100 Virginia militiamen had gathered to seal Brown’s escape route. Trapped in the armory’s fire engine house (now called John Brown’s Fort), Brown was doomed. He was tried for murder, treason, and inciting slave rebellion just one week after his capture and hanged six weeks after the raid.

“Although dead,” says Frye, “Brown did not rest.”

WITNESS TO AN EXECUTION

Brown’s raid, trial, and hanging created a media sensation that fueled passions on both sides of the debate. Across the country, it became increasingly difficult to ignore “that peculiar institution.” The raid provided legitimacy to northern abolitionists who were advocating for a nonviolent end to slavery. And in slave-holding states, weapons from the raid were publicly displayed to stir up fears about the dangers of abolition. Feelings hardened, and these opinions further exposed cultural differences between the North and South that could not be overcome.

When leading John Brown tours, rangers are always delighted to find visitors from northern and southern states in the same tour, Frye says. Ask one how he or she feels about John Brown and you’ll see the other start to squirm, waiting to voice an opinion. “That is the set-up for an outstanding tour,” he says. “That is the Civil War right there.”

To this day, many see Brown as a heroic figure, a true freedom-fighter willing to sacrifice his life to ensure that all black Americans live forever free, Frye says. He is a hero, a martyr, “St. John the Just,” as Louisa May Alcott called him. But others argue that he provoked a war that destroyed their culture. Though no one defends slavery, Frye encounters people who believe violence should never be used to advance a cause, and that it’s always wrong to attack the government over a law, even one that seems unjust. They believe Brown was a criminal—found guilty of murder, treason, and inciting a rebellion—and justifiably executed. “They see the devil himself,” says Frye.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Lionized or loathed, John Brown profoundly changed the trajectory of the nation and the lives of countless Americans. It’s possible that without him, there would be no Great Emancipator. Feeling unsupported by the northern Democrats, the southern states nominated their own candidate for president. That effectively split the party in two, enabling the Republican nominee, Abraham Lincoln—who had distanced himself from Brown—to win the majority’s vote. And without John Brown, southern states might not have beefed up the militias that formed the nucleus of the Confederacy’s military machine at the outbreak of the Civil War.

In the end, some 750,000 Americans died in the Civil War. Nearly 4 million slaves were freed. Before he went to the gallows, Brown penned this prophecy, which he handed to his jailor: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that, without very much bloodshed it might be done.”

About the author

-

Heidi Ridgley

Heidi RidgleyHEIDI RIDGLEY writes about history, travel, and wildlife conservation from Washington, D.C.